Marian Spore Bush

Life Afterlife, Works c. 1919–1945

organized by Bob Nickas

July 9–September 6, 2025

Opening reception Wednesday, July 9, 6–8 pm

Karma

188 East 2nd Street

New York

Marian Spore Bush

Life Afterlife, Works c. 1919–1945

organized by Bob Nickas

July 9–September 6, 2025

Opening reception Wednesday, July 9, 6–8 pm

Karma

188 East 2nd Street

New York

Though Marian Spore Bush painted the flowers, animals, prophets, and architectures on view in Life Afterlife, Works c. 1919–1945, she insisted that she was but the conduit for spirits telepathically controlling her hand from another realm. In communion with, as she recounted, “the souls of those who have lived here on earth from far-distant times down to the present moment,” Spore Bush worked automatically around the same time that the European Surrealists were popularizing automatic drawing and the New Mexican Transcendental Painting Group was representing spiritual concerns through abstraction. However, she did so without any knowledge of then-current avant-garde movements. Life Afterlife is the first exhibition of her work in nearly eighty years.

New York was the locus of Spore Bush’s painting practice, but it took her until her early forties to find her way to both the city and her art. Born Flora Marian Spore in 1878 in Bay City, Michigan, she was the state’s first female dentist. Her mother’s death in 1919 catalyzed Spore Bush’s introduction to visual art: consumed by grief, she purchased a Ouija board and communicated with her mother’s spirit. Continued use resulted in messages from another mysterious source, advising Spore Bush to forgo the board and pick up a pencil. She would come to refer to the entities sending her these missives as alternately “They,” “these People,” or “the People.” In They, her posthumously published autobiography, Spore Bush recounts how the People instructed her to purchase oils and substrates, specified which colors to mix, and guided her hand in the making of her canvases to spread their central message: “there is no Death.” Inspired by their guidance, Spore Bush moved to New York, rented a studio in Greenwich Village, and began painting.

Untrained in oils (or any other artistic discipline), she first worked directly on paper as if drawing. Spore Bush’s autodidactism freed her from the strictures of traditional representation in a manner not unlike that of Forrest Bess, Morris Hirshfield, and other self-taught artists. Early compositions like Japanese Plums (c. 1920s), Water Lilies (c. 1919–22), and Purple Flowers (c. 1919–22) feature florals that, in their sinuous forms and lack of both narrative and adherence to traditional genre, evoke Art Nouveau’s break from the academic strictures of the nineteenth century. The appearance of a purple-robed sage in zoological works like Swans and Man with Camel (both c. 1919–22) suggests that Spore Bush’s paintings, while attentive to the nonhuman creatures of the Earth, are not depictions of the world as we know it. Of these early works, Snake and Strange Creature and Mountain Pinetree (both c. 1919–22) extend furthest into the surreal and supernatural, defamiliarizing Edenic scenes with an unearthly beast in the former and a sky aglow in nonnaturalistic hues in the latter. A few years later, in the curling tail of The Green Bird (c. 1925–30), one begins to see the impasto, sometimes half-an-inch thick, that would characterize her mature work.

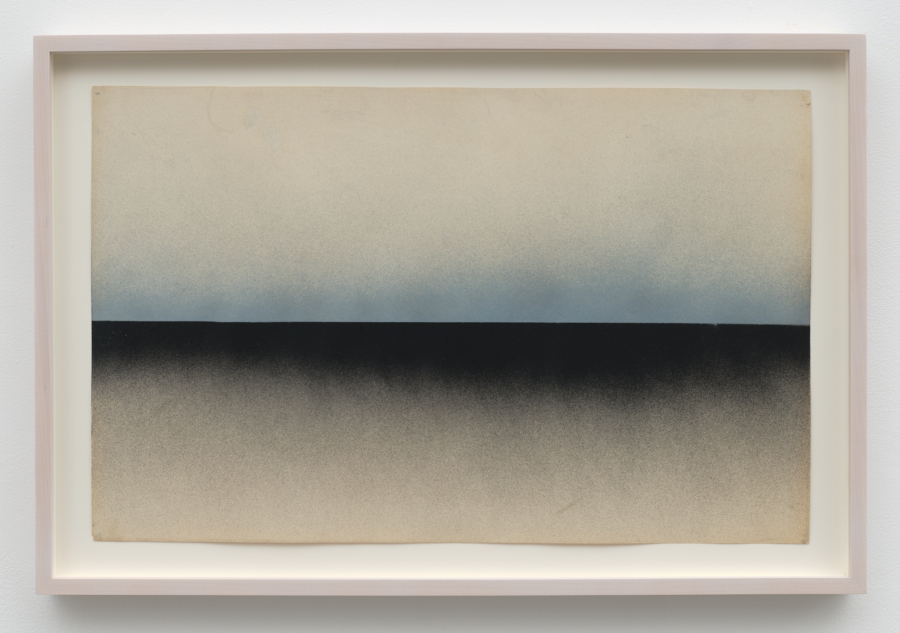

In black-and-white paintings made in the long lead up to and during World War II, which Spore Bush claims to have been warned about by the People at the beginning of the 1930s, the enchanted menagerie is replaced by allegories of the horrors of armed conflict. The Gaunt Bird of Famine (1933) sets the white body of a willow-necked avian against an ominous black sky, warning of post-war starvation; the similarly black-and-white Factories (c. 1930s) represents wartime industry, however productive, as monotonous and threatening; The Pawn Broker (Three Vultures) (c. 1933–34) depicts two stylized birds, flat and black against a sky swirling with brushstrokes, as they fly down torture a man chained underwater. In 1943, the year of Seascape and The Avenger—paintings of oversized fowl swooping down to rescue or retaliate—TIME magazine called Spore Bush a “prophetess” for her prediction of the World War that the United States had finally joined. Seven decades later, a return to her work reveals a prescient vision of unnecessary violence and unprovoked suffering on Earth, tempered with the dream of another, gentler world. Spore Bush embodied this vision not just in art but also in life: known as the “Angel of the Bowery,” she singlehandedly ran and funded a breadline that stretched from the Bowery to Second Avenue, just a few blocks away from where her work now hangs.

by Canada Choate

Marian Spore Bush, Life Afterlife

by Bob Nickas

Who was Marian Spore Bush? Although we have the facts of her life, the full dimension of her lived existence, overlaid with the art she left behind and how it mysteriously made itself known to her, suggests lives plural, an earthly passage spanning less than seventy years while encompassing what she referred to as “life eternal.” The biographical facts are known: born 1878 in Bay City, Michigan, where she would go on to a successful dentistry practice of nearly twenty years; the death of her mother in 1919, and her use of the Ouija board as a means to remain in contact with her, investigations which led to Spore Bush herself being contacted by entities, the spirits of dead artists she said, compelling her to paint, even as she had no previous interest nor training in art; her move to New York in 1920, where she set up a studio and began to show her art, attracting attention for its otherworldly origins even as she didn’t consider herself to be a medium (she would be championed by the illusionist and escape artist Harry Houdini, well known for exposing frauds among so-called spiritualists, but who considered her connection to the supernatural genuine); her philanthropic work in the late-1920s, helping to feed and clothe the needy in a time of economic desperation; her marriage to Irving T. Bush, a wealthy businessman, in 1930; and the major shift in her art to a darker vision in the early 1930s, and an unequivocal position taken against global conflict. She would live to see the war’s end, passing six months later, February 24, 1946. And yet . . .

These multiple engagements and identities over the span of sixty-seven years—identity itself as a vector, as Lee Lozano insisted—evidence lives plural, a life following many intersecting and diverging lines, in itself a concise visualization of the auditory and imagistic guides she would follow in creating her art. The reappearance of her work in this moment, as of many others in recent years, is a reminder that art history is a matter of detective work. The history of art is, or at least once was, parallel to the history of the world. What is this artist’s place in it? How do we locate her in relation to other artists in this period, few of whom were aware of one another in their time? Looming above what is now an alternate view of art’s path—pathways, more accurately—across the twentieth century, is the Swedish mystic Hilma af Klint (1862–1944). She precedes Spore Bush (b. 1878), the German-American transcendentalist Agnes Pelton (b. 1881); the Swiss artist and healer Emma Kunz (b. 1892); Paulina Peavy (b. 1901), who was guided across five decades by an entity encountered during a séance in 1932; and Gertrude Abercrombie (b. 1909), known for her mysterious, dreamlike paintings. All of these artists lived through the First and Second World Wars, and the Great Depression that bridged them. These are the currents, and the undertow, that defined the calamitous first half of the century. The consequential movements of that time, a breaking with the past—Cubism, Futurism, Expressionism, Dada and Surrealism, and Constructivism—may hardly come to bear on these artists. Surrealism is the sole exception, certainly for Abercrombie and Peavy, who drew on the unconscious as an exploration into the realms of the unreal. Here, another figure looms large: the Swiss psychiatrist and illustrator Carl Jung (b. 1875), influential for his concepts of archetypes—recurring mental images and symbols that are universal—and the collective unconscious, the repository of these archetypes shared and understood by all humans.

Were any of these artists aware of Jung? Highly attuned as they were, each in their own particular ways, they didn’t need to be, though Jung’s thought serves a crucial backdrop against which they and others must eventually be considered. For all the various connective lines flowing between the visionary works of these women, which also allow us to see them distinctly one from another, Spore Bush occupies a territory of her own. It is equally wondrous and foreboding, from the early innocence of animals and nature, biblical overtones, edenic gardens, temples and temptation, to the later gathering storm, the evils of war, vengeance and salvation in a dark period of destruction. What is it that set her apart? A late Libra, it may have been her need for balance, equity, ultimately her sense of justice in an unjust world. Formed by tumultuous times, not unlike our own, she was compelled not only to make art but to take a stand against the rising tides. The 1930s may be thought to begin for her with Peace (c. 1932), in which a highly stylized bird, one of her recurrent symbols, floats in the air above a young woman, pale, eyes closed, afloat on a black sea strewn with small white flowers. The image immediately calls to mind Sir John Everett Millais’s enchanted masterpiece Ophelia (1851–52)—she, surrendered to her fate, about to drift downstream and drown. In 1932, peace was not meant to be. The decade closes for Spore Bush with a painting she titled World Aflame (1939): a devilish figure blows fire upon a darkened globe. This image uncannily recalls a work by Hilma af Klint, painted seven years prior, A Map of Great Britain (1932), in which a figure, also positioned in the lower-right corner just as in Spore Bush’s composition, expels a firestorm upon England. This foretelling of Nazi Germany’s blitz against the country, which began in the fall of 1940, preceded the catastrophic events by eight years. While art may not often predict the future this directly, we acknowledge its power to record what we only come to know in retrospect.1

The sea, with its mysteries and depths, appears in much of Spore Bush’s later works. These are almost exclusively rendered in grisaille, and so water appears impenetrable, concealing what lies beneath, unable to reflect light. The structure central to one of her greatest images, The Pawn Broker (Three Vultures) (c. 1933–34), is an inverted triangle with two birds at the top, gracefully rendered as always, not seeming vulturous. They descend toward a man who stares upwards at them, his large bald head barely held above the surface, a chain wrapped around his neck. The birds’ near-human eyes are set within what might be black cowls. They may be executioners of a kind, or merely availing themselves of easy prey—someone who had conducted himself in much the same way? The Avenger (1943) offers another triangulation, an image of three figures hanged from a bare, wintry tree. A giant, dark winged creature glides towards them against the sky, uncharacteristically blue for Bush in this period, though solemn. In the same year, she would paint Seascape, again featuring an outsized, highly stylized bird, this one brightly rendered, taking wing over white-capped waves. A figure near the bottom-left corner lies flat to a small raft, cast adrift, lost at sea, the bird’s attenuated red beak seemingly about to poke him, maybe only in curiosity. Is he alive or dead, or clinging to life as he is to the raft that keeps him from an otherwise certain demise? Surely, Spore Bush believed in justice, but she also believed in salvation. One of her early works, The Red Ship (c. 1919–22), created twenty years prior—sails full of breath, riding high on the sea—may have been the original conveyance for the man on the raft. Reconsidering the life, the multiple lives led, of its creator, and the lives she encountered in time-space beyond, we can think of it as having been this artist’s conveyance as well.

What attracts us to Marian Spore Bush circa now, a hundred years, or nearly, since she brought her vision to the world? It wasn’t hers alone, and in many ways. The story of her afterlife, clearly, is that it goes on.

Note

- I am indebted here to recent observations made about this work of Hilma af Klint’s by the painter Anna Conway.