September 27, 2021

Download as PDF

View on Interview Magazine

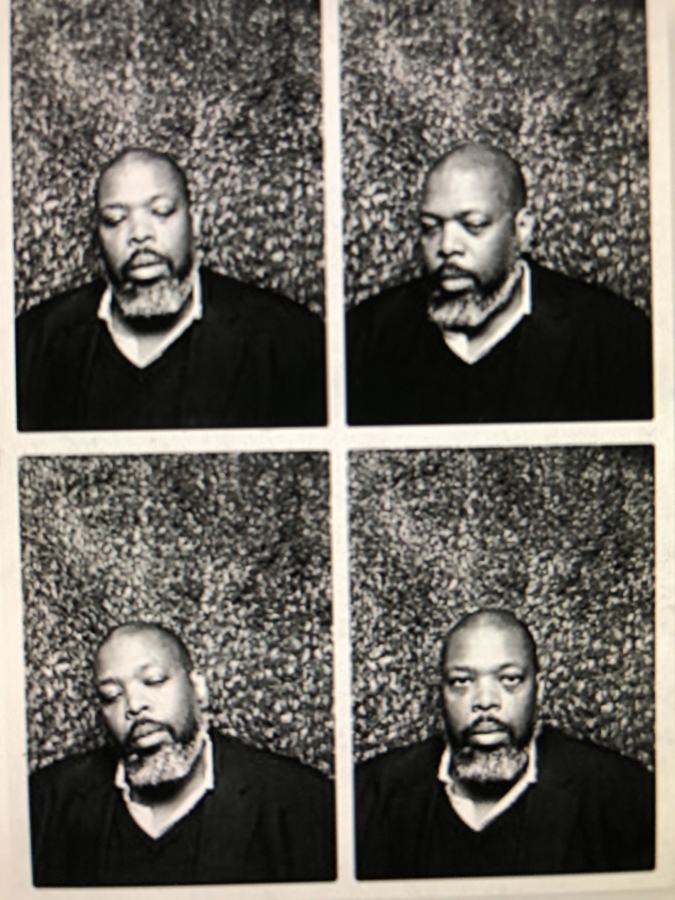

Hilton Als. Self Portrait London Photo Booth, 2017.

“One of the things that’s very important for me, as a thinker,” says Hilton Als, “is to show energy not defined by race, gender, or class, but energy as defined by the artist.” Indeed, the writer, curator, and theatre critic has spent much of his career examining the exchange that occurs between audiences and works of art. As we enter a new era of the pandemic, Als is committed to reviving this exchange, reliant on rituals of community and gathering, that has been sorely missed during the year’s many lockdowns. This celebration of joy and togetherness is the focus of Get Lifted!, an exhibition curated by Als that is currently on view at New York’s Karma Gallery. The show, which features a selection of works from artists including Alice Coltrane, Ana Mendieta, Peter Hujar, Tabboo! Diane Arbus, Ntozake Shange and others, is an examination of transcendence. For Als—and for the artists whose work he displays—this is a matter of pushing past all forms of constraint: social, political, earthly or otherwise. To learn more about the exhibition, Interview sat down with Als to discuss the role that art can play in rebuilding our fractured culture.

———

ALEXANDRE STIPANOVICH: What was the original concept of this exhibition?

HILTON ALS: We had a long year. We had a year to think about things, and as I started to gather objects and feelings, I noticed that I kept coming back to this idea of freedom over and over again. The images that I chose had an ecstasy about them— they couldn’t be contained in the frame of a piece. I feel that there’s something that links these works, even though these artists are so different. I think the thing that links them is that feeling of catharsis— the real curatorial effort was to space out the material enough so that the viewer could take that feeling in. It was like making the gallery an object of curatorial intention, and I wanted the viewer to be as important to the show as the work. Also, being uplifted by a show is so significant to me. It’s so special to me that people have been feeling that way about this show.

STIPANOVICH: How does physical space play a role in your conception of repression and injustice?

ALS: During the dark days of COVID, I kept seeing exhibitions that were about segregation and racial or gender-based separatism. There was no real discussion about what was making us whole, what was making us connect. So, as I was thinking about this show, I was wondering, “How can I make this about connection?” Those of us who were fortunate enough to be alive in spite of the pandemic didn’t necessarily need instruction on how to be human. We needed an acknowledgement of what brings us together as a species. That’s really where the idea for the show came from, and why I chose to include the artists that I did. As a writer and a curator, I’ve always been curious about what was that kept these artists going? What was it about their vision that spoke to us about community and empathy?

STIPANOVICH: You’re interested in resilience?

ALS: Yes—how important it is for thinkers and artists. They always want to escape the parameters of being confined to a body, confined to a race, confined to a gender. One of the things that was very important for me, as a thinker, was to show energy not defined by race, gender, or class, but energy as defined by the artist.

STIPANOVICH: As a former theater critic, live energy must be vital to you.

ALS: Especially this year, when people couldn’t be together. One of the things that was interesting to me was how to build a community out of fracture.

STIPANOVICH: There are many performance artists in Get Lifted! You organized a performance at this gallery not long ago. How important is a live audience to this transcendence of boundaries that you’re talking about?

ALS: The artist is a portal for us to access a feeling of being transported. The artists that I chose really were transformative in their time. We’ve been told for so long now that only certain people can look at or produce this kind of art. It’s a very frustrating argument for me, because one of the things that I love about making art is that it’s limitless.

STIPANOVICH: The exhibition spans two galleries. The first gallery focuses on documentation and art display in a more traditional way, and the back gallery—which contains works by Alice Coltrane, Ntozake Shange, Ana Mendieta and Paul Pfeiffer— feels more like a portal. Can you elaborate on this layout?

ALS: With the artists Ntozake Shange and Alice Coltrane, I really wanted to show how much of their work was about ascending. Alice Coltrane made art about leaving this body for something spiritual and higher. Ntozake’s work is about pushing past other people’s views about gender and sexuality. So in a sense, the second gallery is a portal into that transcendant space. Paul Pfeiffer and Ana Mendieta focus on how the body is transformed.

STIPANOVICH: How did you encounter the work of Alice Coltrane and Ntozake Shange, and why are these two women so important to you?

STIPANOVICH: How do you think of Alice Coltrane’s relationship to the spiritual?

ALS: Alice and John Coltrane started their spiritual journey together, and after his death, she continued that work as a brilliant composer, harpist, and pianist, using chanting and circular rhythms to build worlds out of sound. She knew that sound rose, and so the body must rise too. The spirit must rise, I should say.

STIPANOVICH: These pieces in the show work very subtly on you. They’re powerful, but they’re not in your face.

ALS: Absolutely. I despise declaration—of anything. I hate telling visitors how to feel when they look at a work of art, and everybody should be free to experience it how they want. My aim was to make sure that feeling of ecstasy is something that’s offered, but it’s not something that’s forced.

STIPANOVICH: Can art change you?

ALS: You have to be porous and open when you walk into a gallery. Otherwise, there’s no way for artist and viewer to communicate. I want the show to be taken as an example of how communication can work when we leave ideology or politics aside. It’s based in the belief that people are capable of making up their own minds and feelings about a given idea.

STIPANOVICH: In your mind, is a curator a storyteller? A historian? An entertainer?

ALS: All of the above. You have to put on a show, and people have to be entertained. And at the same time, you want to uplift them deeply and personally. At the same time, I wanted it to be instructive without preaching. So I think that a curator, at his best, is all of those things. At least, I try to be.