October 2015

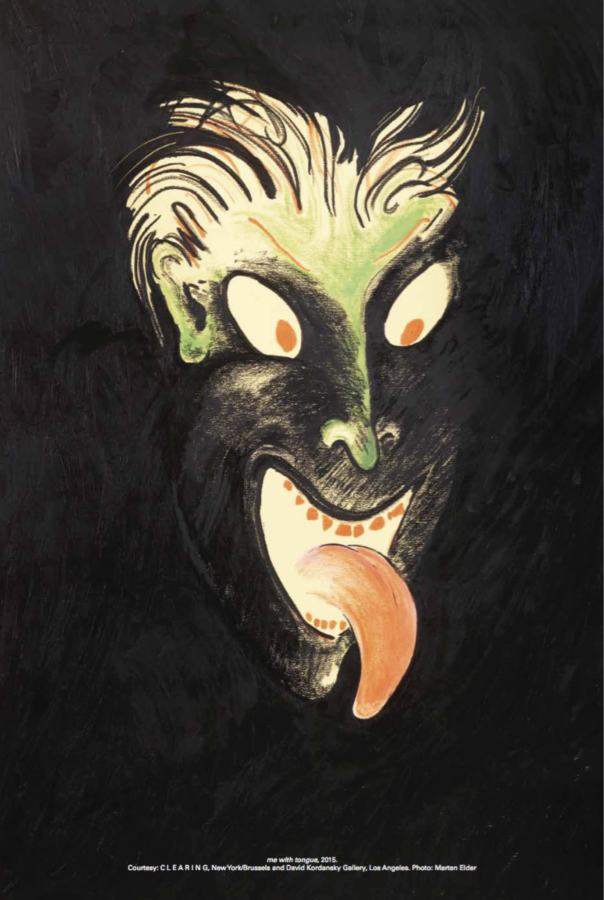

The devil lurks in the details, which might even be the jarring anthropomorphic suggestions of a plucked chicken. For Calvin Marcus, the devil is simply a device of introspection, a distortion of perspective, or a disturbance needed to get off the beaten track.

MICHAEL DARLING

One of the things that strikes me about your work is that I think from an outsider perspective people might see a certain kind of schizophrenic quality to it. One body of work on the surface seems quite different from the next body of work. Could you talk a little about that as a strategy and if there were other artists who have helped you arrive at that way of working?

CALVIN MARCUS

I think the ways that I formally approach certain ideas tend to include a different material problem or situation every time I develop a body of work. I worked for Laura Owens for a few years and was really excited about her ability to not stay still. It made me realize the power in not feeling like you have to do any- thing every single time or cultivate an audience for something that people are expecting you to do.

MD

Is that a kind of rebelliousness

or an unwillingness to be pinned down, or do you actually see it as a longer term approach to keeping your practice alive and keeping things interesting and evolving for you?

CM

The latter, absolutely. I think it’s a way of keeping myself invigorated. Every single time I have to learn how to do something. I don’t want to become a master of anything.

MD

There is a certain project–based approach that you have that reminds me of the way your UCLA teachers, Charles Ray or James Welling, work. They’ll have a new problem at hand and they’ll go to extensive lengths to accomplish that task. Does that hold any kind of water for you, learning from artists like that?

CM

Those two examples are really good because both of those artists are interested in things that take an immense amount of time and research to do, even when there’s some other way that you could get to a finished artwork much more quickly. It’s about the journey to carry something out.

MD

In a recent body of paintings that you showed me, you described the lengths you went to in order to have oil stick paints specially fabricated to match the viscosity and color of Crayola crayons. I was fascinated by the single–mindedness of that. How much of that is important to a viewer looking at the work?

CM

I think it’s exciting to talk about the process in the context of the studio, but I’m not so sure that the efforts invested in having those things produced are important in the understanding of the work.

MD

It seems that there is a tangible strangeness about these new paintings that feel like they might be from another time or feel unusual being rendered into this large scale. I think you have found this strange in–between space and that maybe this is the payoff for all the behind the scenes work you put into them.

CM

Yes, I can’t tell if they actually look old or if they just evoke a strangeness from their uncanny material repertoire. There are things I put great effort into, like making the canvas look like a certain type of paper, which is really just some paper I found in a sketchbook.

MD

I sometimes question whether the quest for novelty is superficial or if the job of the contemporary artist is to show us something new. It seems like with these different procedures and processes you’re also trying to find new and unchartered territory.

CM

I feel like my job is to be searching for something that changes the way I look at other things. I think a lot of the processes that I engage with, like oil painting, are about as old as they could possibly be, but there’s still a way to make them unique, like inserting yourself into it and shifting it into something only slightly different.

MD

Do you think that disruption is a useful word to describe what you’re doing?

CM

Yes. One of the things that really excited me about the paintings I showed at CLEARING, besides the fact that they were being used as green projection spaces, was that they were also large–scale green monochromes. People always tell you that green paintings are the worst.

MD

For sales?

CM

For sales. But also color–wise, they came from this idea of synthetic color–it’s not a landscape painting color, it’s actually this very synthetic green, which is also like a green screen. It really produced this weird, empty projection space. The true function of a green screen is exactly that: digital image replacement.

MD

And in LA it seems like that’s a very fitting ground zero to be work- ing with.

CM

Yeah, near the film industry. The way the green paintings came about was initially an interest in the tradition of devil masks. I noticed that throughout many cultures the motif shared certain conventions such as the pointy horns and goatee. But when I looked at the way the devil is portrayed in contemporary culture I noticed that he/she is never really a third party; the devil is usually just yourself dressed up on one shoulder and yourself again as an angel on the other, giving advice. This seemed like proof to me that the devil is not a monster; it’s a warp of your own perspective and a distrust of yourself. The devil to me became a kind of introspection, where one goes inside and indulges. I was looking at the body of a plucked chicken and realized that when the legs were pointed up, it sort of resembled the horns of one of the devil masks that had inspired me. So I sculpted my own portrait within the body of a chicken (in clay), which grasped that visual disruption or warping, that to me was devilish.

MD

So they are kind of, in your mind, self–portraits in a way?

CM

Definitely. And to think about the chicken faces in terms of disruption, having a composition with something directly in the center is a no–no. So I guess that would be one example where I was intentionally disruptive, which is not so much about a “fuck you” as it is about my own sense of humor.

MD

Like investigating why these sorts of rules have been passed down and testing them?

CM

Yes. I also wanted to create some type of confrontation where you’re arresting a viewer, creating an experience where the space in–between the paintings and the energy in the room is activated through insistent seriality and really intense color.

MD

I think that leads to another question on your interest in seriality. It seems to me that your paintings test viewers and their capabilities of studying the differences from one thing to the next. There is a structure that connects them all but there are all of these variations in–between. Is that what you’re after, fine–tuning people’s sense of scrutiny?

CM

It’s that and it’s also this desire to take over a venue and have it be redundant, imprinting this memory that you can’t really evade. There’s something about repetition that lasts. It’s much harder to forget something when you have to see it ten times. In terms of fine–tuning, it’s asking the viewer to look at variation in a different way; all the compositions are the same, centered; each portrait holds a different expression.

MD

Could it also be a way of maintaining a certain rigor in your practice?

CM

Yes. There’s also a boredom that can be produced from doing the same thing over and over again. It’s certainly a way to launch you into something else, which I think is really important.

MD

So do you usually stop when you feel like you’ve exhausted the possibilities of a project?

CM

I do stop and move on to other things or at least start other things while that is still happening. It’s not to say that the ideas are boring to me, because sometimes I’ll look at a green painting that has hung in my studio for a year and I’m still excited when I look at it.

MD

It seems like you don’t shy away from challenges that then give you a structure or an arena around which to work. I think one area where I really saw this was in these new paintings you’re making for your upcoming exhibition at David Kordansky Gallery. Can you talk a little bit about the multidirectional nature of those paintings and how they were made?

CM

The paintings are four by eight foot, off–white expanses made on portrait linen. The drawings on them are all done with a black crayon. Even though they’re on can- vas I want them to read as drawings. I work on them either flat on the ground or on a tabletop. And since I walk around the canvases and add to them in a circular fashion the paintings can be hung vertically and horizontally and upside–down.

MD

One thing I noticed is a real variety of different types of imagery and mark making from detailed and illusionistic to flat and even crude. Are you intentionally trying to engineer a certain variety into each work?

CM

I work on them in stages. I’ll make marks on one canvas and then cross–pollinate that drawing onto different canvases in an effort to make the entire room feel like one big drawing. Certain things sometimes end up on five different canvases. Some days I’ll draw in perfect perspective and other days I’ll make drawings that are really flat and cartoony.

MD

Would it be too grandiose to say that in each of those you’re trying not to be limited to one language but to open up many possibilities for yourself and maybe even for the viewer?

CM

I make an effort to have the paintings be as generative and open as possible. I think the way the canvases are prepared and the way that I’m moving circularly around them attempts to depict an interior brain space where there isn’t gravity but ideas and thoughts that are colliding and moving. There are certainly things that don’t line up.

MD

And that’s fine with you?

CM

Yes, because there isn’t one way to read the works, and there is some kind of desire in these works to not be pinned down to something narrative. It’s really about having the painting be this influx thing that finds a sort of power in being open, with moving parts, but at the same time is finished and precise.