2015

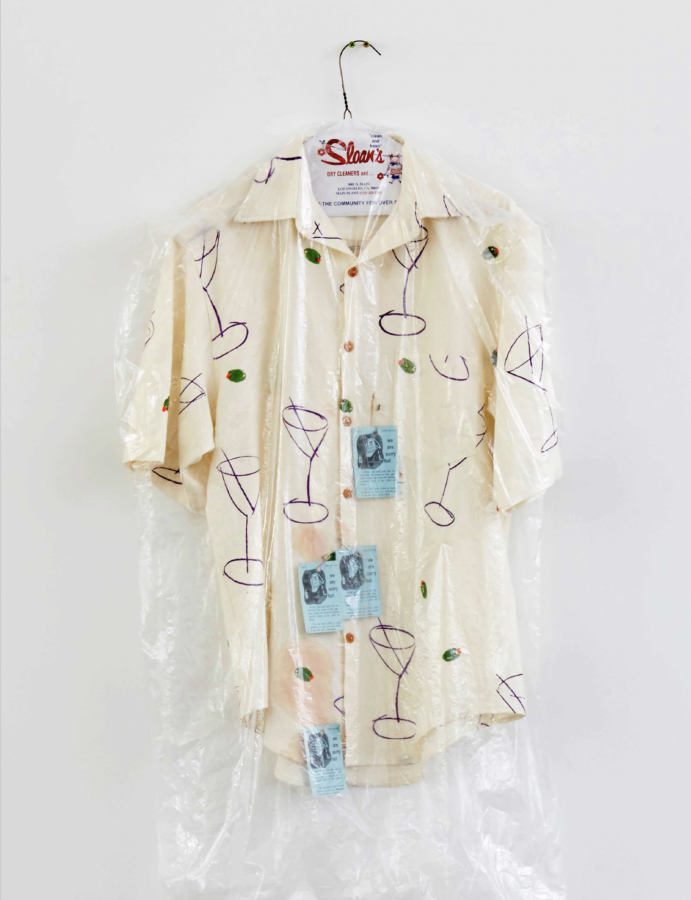

Calvin Marcus, Dry Cleaned Shirt with Martinis, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo Credit: Lee Thompson

As visitors arrived to Calvin Marcus’s solo debut in New York they may have seen, down the way and standing opposite from the main entrance of the gallery, the anodized aluminum door to the artist’s studio in Los Angeles. Before immediately turning right into'”the first gallery, visitors may have also caught a glimpse of an indiscernible image painted in a rectangle on the top half of the door-but then again, it was far away and not en route to the main event. After snaking through a sea of bright green monochrome paintings, each colonized by a single ceramic chicken (grinning, teeth out), the third and final gallery space presented viewers with the exterior-facing side of said door. The aforementioned image nestled in the rectangle now came into focus: a rudimentary clock suggesting that. Marcus was, like his transplanted door, “out of the office.” The defunct studio door was similarly inoperable· having been shipped across the country and installed alongside other painted works from Marcus’s studio, this work had not been titled, was not for sale and, unlike its more traditional and chicken-adorned allies, could be viewed from both sides.

Today, the space in Los Angeles where the door once was is now vacant. Where it previously divided Marcus’s studio from his domestic area, one can now view recent artistic productions (one group of which will soon be on view at Peep- Hole in Milan; another opens next year at David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles) from a number of humble vantage points, including the artist’s bed, couch, refrigerator, breakfast table, and, most notably closet.

Along one wall of the studio, adjacent to the domestic space hangs a series of identical linen resort shirts that showcase an all-over screen-printed pattern of martini glasses and their accompanying green olives. Together, through the familiar marks of a paper-wrapped hanger and impervious plastic sheath, they parade the banal maintenance of a collective trip to the dry cleaner-a reasonable allusion, given the fact that, upon closer observation, each shirt has been stained to the point of no return (as noted in a number of apologetic dry cleaner tags garnishing the front of each garment) by the seemingly reckless consumption of red wine and other less identifiable but equally gluttonous victuals. The martini shirts, the patterns of which are based on Marcus’s own proportions, archive personal desire, fully acted upon to the point of becoming physically inerasable.

For Marcus, to exhibit publicly is merely to relocate isolated acts of desire from their private context. The stained shirts will soon have to depart from the security of the neighboring closet. Yet the door, previously separating the personal (domestic space) and the soon-to-be public (studio space), continues to offer a mental partition in the context of the gallery. To approach the interior-facing side of the door, visitors would have to bypass the exhibition and walk a long corridor leading to the gallery offices. By the end of it, positioned next to the restrooms, one would nave found the other side of the door, with its coat of paint, effectively visible through the glass on the exterior-facing side (and the gallery side), still attempting to maintain a sense of privacy.