September 12, 2016

Download as PDF

View on The Wall Street Journal

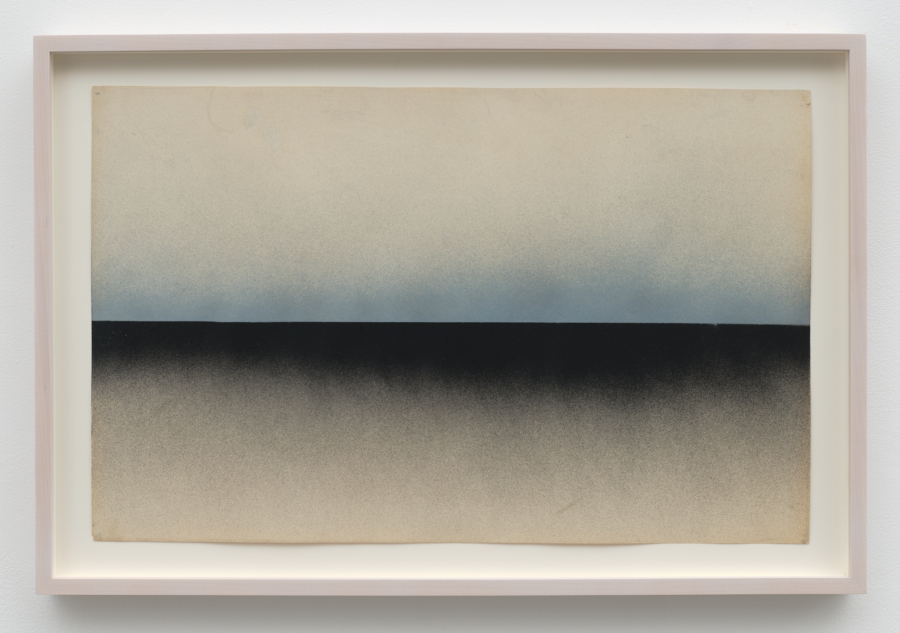

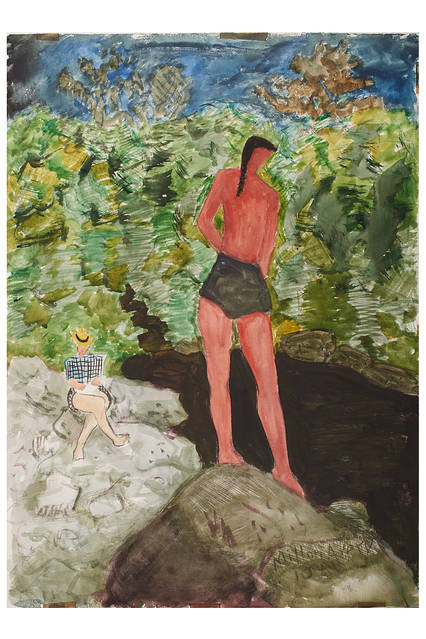

‘Thoughtful Swimmer’ (1943), by Milton Avery. Photo: Artists Rights Society

The Bennington Museum’s “Milton Avery’s Vermont” is as close to a perfect show as mere mortals can mount, small in scale, with beautiful objects, expertly interpreted, and with many surprises. Every art lover needs to learn more about this work and the museum itself.

Between 1935 and 1943, the undiscovered, city-based Avery (1885-1965) and his family stayed, sometimes for months, in Jamaica, a town in the southern part of the Green Mountain State. The scholar and critic Meyer Schapiro, Avery’s good friend, had a house there and recommended its quiet, beauty and charm. Green is indeed a constant in the Vermont landscape, and the artist who would become known as “America’s Matisse” because of his coloristic fervor rose to the challenge of finding harmony and verve in this and the many supporting colors that constitute Vermont’s mountains, fields and sky.

It was immediately after his Vermont summers, when he was close to 60, that one-man shows at the Phillips Collection and Paul Rosenberg & Co. brought him fame. These and other shows at the same time drew heavily from Avery’s Vermont period.

A great colorist like Avery coaxed an encyclopedia of greens ranging from the fresh emerald of “Spring Landscape” (1940) to the more stately, mature hues of “Thoughtful Swimmer” (1943). Blue fir forests abound in Avery’s Vermont work, as in “River in the Hills” (1940), where he foregrounds and magnifies firs as if to insist that not everything is green here. In “Small Farm” (1937), cultivated fields allow for varieties of yellow, brown and pink.

Avery often stayed into the fall. Each fall in Vermont is both different and stunning, and over the years he embraced the many reds, purples and yellows nature supplied based on weather occurring months before.

“Three Cows” and “Old Mountain,” both from 1943, at the end of his Vermont visits, are spatially flat. Figures are mere contours. These features link him to abstraction. But though Avery’s closest artist friends were Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, all Abstract Expressionists, he hewed to recognizable subjects that accommodated the new vocabulary. His palette is certainly a subjective response to his subjects, and here Avery draws from the Fauves, but he does not veer too far from the rich colors before him, and his dash marks coalesce into persuasive trees and cows. Nature cued him. In the 19th century, Vermont was almost completely deforested to promote pasture and crops. The woods Avery saw were mostly scrubby or packed with fast-growing conifers and newer trees with stick-like trunks and branches. Dabs and simple lines of paint sufficed. The fields at the base of the hills rolled gently, inviting representation by means of broad blocks of color on paper. Vermonters are economical with money and words and crisply candid. The local spirit seemed to match the artist’s vision.

The catalog by curator Jamie Franklin and the critic Karen Wilkin, a Wall Street Journal contributor, fortify an aesthetic feast with new takes on both Avery and American art before the start of the Atomic Age. I thought of many artists as I visited the show—John Marin, Charles Burchfield and Marsden Hartley among them—yet Avery’s Vermont work is hardly derivative. It’s an independent part of its era.

The Bennington Museum, in the southwest corner of Vermont, was once a quaint, packed trove of antiques. It celebrated a Vermont aversion to tossing out good things only because they were out of style. A new director and curator haven’t completely abolished this look. The permanent collection space, much pruned, is still quirky and fun. Esteemed locals like Norman Rockwell and Grandma Moses are as present as ever. Robert Frost is buried in the old church graveyard overlooking the museum. In Vermont, the past is never far.