December 19, 2016

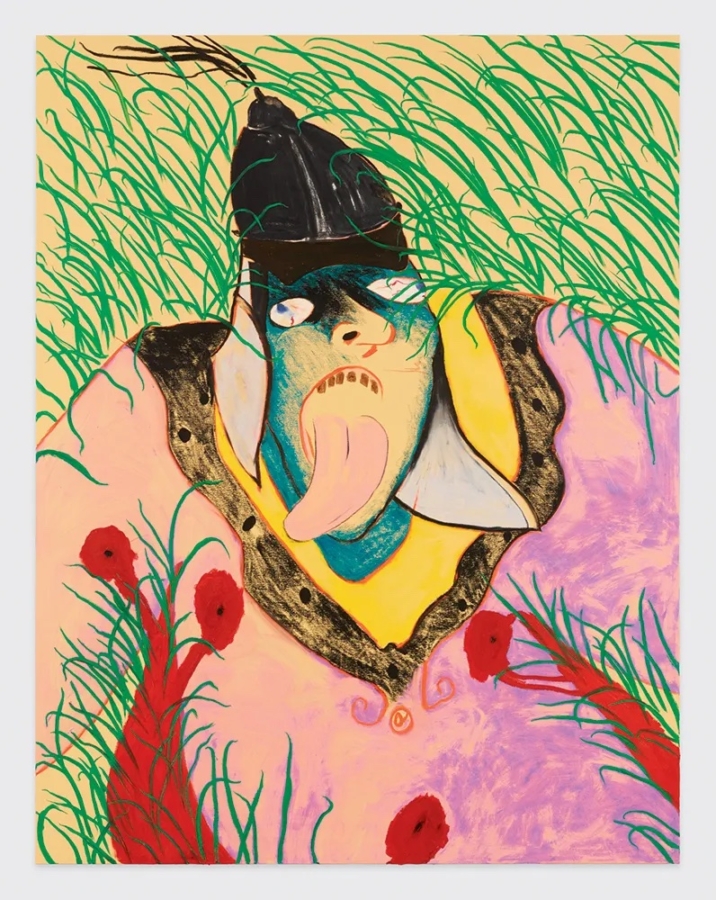

Calvin Marcus: Dead Soldier, 2016, oil stick, Cel-Vinyl, watercolor, and emulsified gesso on linen-canvas blend, 101½ by 79 inches; at Clearing.

Calvin Marcus’s exhibition at Clearing, titled “Were Good Men,” had a kind of nervous energy running through it. The show assembled thirty-nine oil-stick paintings whose crude rendering recalls that of children’s drawings. All the paintings have backgrounds the color of dry earth and bear grasslike masses of bright green vertical or diagonal marks—sparse on some panels, dense on others—and about half of them feature the figure of a dead soldier lying on the green turf. The soldiers have contorted bodies clad in variously colored uniforms, bloated faces tinged purple, green, or brown, bulging eyes, and long, pink tongues lolling out.

The strength of the show was greatly reinforced by the large scale of the canvases (all around one hundred by eighty inches) and by the mazelike installation in which they were displayed, with the works hung in a sequence that coiled along the walls of three connected rooms, producing a dizzying panoramic effect. Walking through the space was like wandering among constantly shifting vistas of a hallucinatory combat zone. The dead soldiers, frozen in bizarre dancelike postures, their arms flung about, their hair entwined with the grass, looked both pitiful and ridiculous. Their uniforms and insignia appeared to have come from different nations and historical eras, and the overall scene brought to mind the medieval genre of the danse macabre, with its poignant depiction of the universality of death.

Since Marcus’s first solo show, in 2014, the young Los Angeles–based artist has developed a body of work that includes painting and drawing, sculpture, ceramics, mixed-medium objects, and installations. Much of this work reflects a preoccupation with personal and artistic identity. He has made various self-portraits, for instance, including crayon drawings and paintings in which he appears with his tongue sticking out, and ceramic pieces showing his face sculpted on the bodies of clay chickens attached to monochrome green paintings. His recent exhibition at David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles was titled with a spoonerism of his name: “Malvin Carcus.” It featured custom-made linen shirts that he designed and wore for some time before sending them to dry cleaners and presenting them in the gallery complete with receipts and plastic wrappings. Accompanying these works were large “Automatic Drawings”—canvases he covered with gestural marks and doodles made with black oil crayon and Flashe paint. Presented together, the shirts and paintings could be viewed as an ironic commentary on society’s fetishization of the male artist’s hand and personality, but they also embraced and reinforced this myth.

Marcus’s new series is a welcome departure from such solipsistic previous work. Begun as a group of small crayon drawings, which were then projected onto the canvases and traced, the paintings combine vigorous mark-making with evocative imagery. In the agitated images of dead soldiers, Marcus transposes questions of male identity and representation into terrain broader than that of his prior investigations, tapping into themes and anxieties concerning the human hunger for power and drive to self-destruct.