January 17, 2017

Download as PDF

View on BOMB Magazine

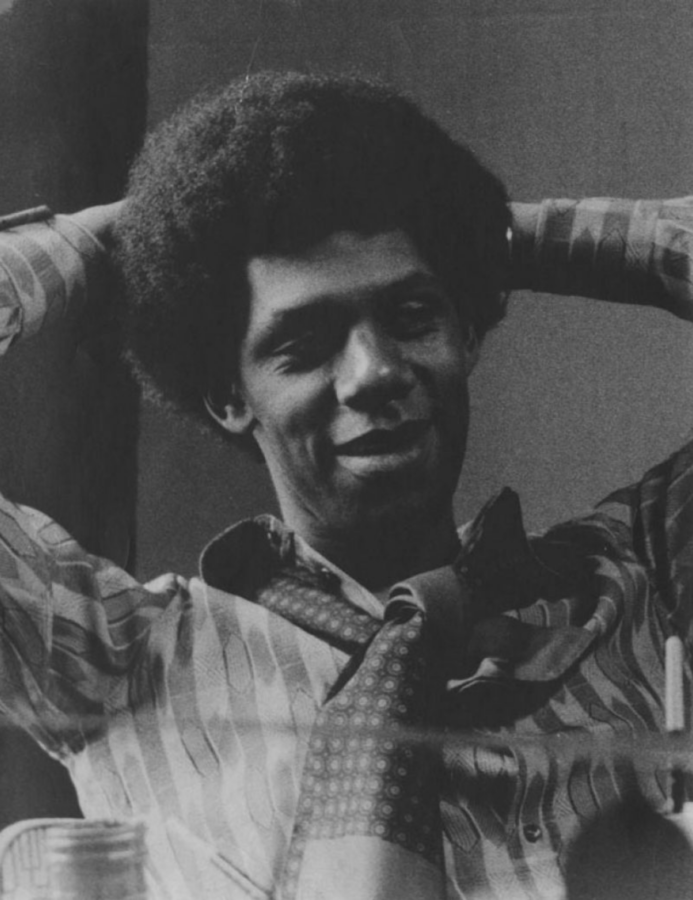

Peter Bradley, 1971. Courtesy the artist.

Peter Bradley is fast: fast-talking, fast-thinking, fast-living. So fast, in fact, that many of us are still trying to keep up with him today. Brimming with a certain velocity and vigor that has brought him around the world and back, all the while keeping a great sense of class and determination, Peter Bradley reached a level of success in the New York City art scene of the ’70s and ’80s that is like no other. The wearer of many hats (art dealer, curator, painter, sculptor, musician, teacher), Peter’s story is one worth knowing, full of great anecdotes and historical narratives that reveal a picture of the past that is otherwise still unknown to many scholars and historians. From his time as Associate Director at Perls Gallery on Madison Avenue to curating the seminal exhibition, The De Luxe Show, 1971 in Houston, Texas to his time spent making sculptures in South Africa during the apartheid in the ’80s to touring with jazz musician Art Blakey, Peter has proceeded through life with irresistible swag and toughness that is both infectious and, at times, overwhelming—never looking back, always moving forward. For this edition of BOMB’s Oral History Project, Peter invited three longtime friends and colleagues to interview him: poet Steve Cannon, poet and writer Quincy Troupe, and artist Cannon Hersey. Focusing on different periods of his life and career, each interview delves deep into the world of Peter Bradley; one full of mystery, grit, and color.

—Terence Trouillot

Peter Bradley & Steve Cannon

Steve Cannon

Now, Peter, as far as I remember, when we first met you were working at Perls Gallery.

Peter Bradley

I was associate director of Perls Gallery, 1016 Madison Avenue, from 1968 to 1975. I traveled all over Europe and America selling Calders, Picassos, Braques, Legers, and Soutines—all the French twentieth century modern masters.

SC

All I remember is you with the three-piece suits on.

PB

I never wore a three-piece suit, they were all custom made at—

SC

Custom-made!

PB

Custom-made at Meledandri, on Fifty-Fourth Street between Park and Madison Avenues. Roland Meledandri. He was really good. He didn’t care who was in the goddamn store when I came in. He would say, “Oh, gotta take care of Peter because he’s got to go, he’s on his lunch hour.” And a lot of these famous people waiting in line would say, “Who the fuck is this nigger?”

SC

So when did you start painting and getting serious about art? And how did you meet Kenneth Noland, and all those Abstract Expressionists?

PB

Well, you know I went to great art schools [the Society of Arts and Crafts in Detroit and Yale University in New Haven], and I’ve always been dead serious about art. I had a loft on Broadway that William T. Williams found for me.

SC

Well, how did you meet William T. Williams?

PB

I was at Yale University with him.

SC

I see, uh huh.

PB

It was nice of him to find that loft for me, because I was busy on Madison Avenue and traveling a lot. And I just didn’t have the knowledge to figure out how to get a loft in downtown Manhattan. So, when I left the loft I gave it to him instead of selling it.

SC

Now, where did you live previous to the loft on Broadway and Bond Street?

PB

I think I had a place in Lenox Terrace. No, no, no, that’s way before, way in the past. God, I don’t remember, Stevie.

SC

I used to come visit you there on Broadway all the time, and hang, blah, blah, blah… That’s when you introduced me to Ken Noland. So how in the hell did you meet Noland?

PB

Noland lived downstairs from me on Broadway. He was extremely interested in me for some reason. I don’t know why. But he paid a lot of attention to me and told me he thought I could be a great artist if I just focused.

SC

Oh, I see. I remember that bar across the street from your place, too. What was the name of it again?

PB

Saint Adrian Company.

SC

Everybody used to go there.

PB

Well, that was an alternative to Max’s Kansas City. I think I was the only black person allowed to go into Max’s Kansas City. Mickey Ruskin sat on that chair outside the bar and told people whether they could come in or not. But I wasn’t allowed to cash checks there, even though I did have a Ferrari parked outside.

SC

When and where did you have your first show?

PB

At André Emmerich.

SC

Okay, now what year was that?

PB

It was 1972. I did six shows with Emmerich.

SC

Okay, we gonna back up now, ‘cause we gotta go back to the ’60s. Let me put it this way, Peter, when did you get that loft down on Broadway? What year was that, when you were living next to William T. Williams?

PB

Oh I would say ‘68, ‘69.

SC

Yeah that’s when I met you.

PB

Yeah. I think we met at Saint Adrian. It’s hard to remember.

SC

I vividly remember your whole apartment. It was so beautiful the way you redesigned it. It was classic as a motherfucker. I remember you had a studio in the apartment where you painted. And Williams was living next to you too. When Mel Edwards first came to New York, he stayed with William T. Now, were you showing in the ’60s at all?

PB

Yeah. I showed at the Museum of Modern Art. MoMA had a group show, In Honor of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968, months after King’s assassination. I had a painting in that show. I was also in a show called Art for McGovern, in 1972. It was a joint exhibition between Pace Gallery and the Sidney Janis Gallery to raise money for George McGovern’s election campaign. I showed at a lot of places. But they weren’t giving contracts out to black artists at the time. But Noland and Clement Greenberg were instrumental in my success and they knew Emmerich Gallery—which was a premiere gallery of its time.

SC

So, how did the Museum of Modern Art know about you before you started showing at Emmerich?

PB

Maybe something got out from Perls, I’m not quite certain. I made a lot of money at Perls—a lot of money. And they were quite generous. They made sure I had everything I wanted in the world—everything but freedom. They wouldn’t even let me go out to lunch. I had to eat lunch with them inside the gallery because they didn’t want me to eat lunch with the girls from Sotheby’s.

SC

Right. Yeah, I got you. (laughter) Now, that was about the same time when I met your son, wasn’t it? He must have been a little baby at the time.

PB

My son Miles and my daughter Lisa were born in Detroit. I went to Detroit in 1959. I stayed with my sister, Ellen. She had a house there. I was at the Society of Arts and Crafts in Detroit for three years. I dropped out and came to New York.

SC

Well, I met your wife at the time, [Grace Burney] here in New York, I remember that.

PB

If you met her, you must have met my son.

SC

‘Cause she just came through for a visit or something.

PB

Well, she lived here for a few years, but she couldn’t adapt to New York living.

SC

Right.

PB

And I just didn’t have time to play the game because I was interested in painting. When she first came along I was working at a framing company making frames. And I’d work all day long at the frame shop and paint all night on Ann Street, my first studio in New York.

SC

Yeah.

PB

I first got to New York in 1963. I met Alex Katz’s wife Ada at the framing company. She worked there with me. All painters worked at framing shops at the time. She was a very funny lady. Tall, skinny girl. She said to me, “You need to get a studio,” I was like, “Alright, I’ll get a studio. Find me a studio.” She told me about a loft downtown on Ann Street, which I rented. And from Ann Street I would leave at two or three o’clock in the morning and go back up to Lenox Terrace in Harlem, where I was living, and back to work the next day.

SC

Now, let me shift real fast. How did that show come together that you curated for the de Menils in 1971?

PB

Well, I used to spend a lot of time talking to Mark Rothko. He used to come to Perls and spend at least two to three hours there every week. That’s how I got to know him. He’d come visit me on Thursdays. He smoked so many cigarettes his whole chest was always covered in ashes. And the Perls [Dolly & Klaus] gave me a lot of flack for spending so much time talking to “this idiot,” as Dolly called him. They hated him ‘cause he would come over all the

time and not buy anything. I think that Rothko turned the de Menils onto me. I’m not quite certain. I still don’t know how it ever happened. But I know it was John de Menil who came to Perls and asked me if I would put a show together for him. And I told him, “Why me?” And he said, “I think you’re the best person to do this, that we know of.” And I said, “Well, why don’t you take a look at some other black people? Because I’m really busy. I’m really busy.”

SC

Yeah.

PB

But later John de Menil called me on the telephone and begged me to take the job.

SC

‘Cause I remember Joe Overstreet had a show down there in Houston before you, with that crazy guy who died, the dope fiend… What was that Jewish artist’s name? Oh, I can’t remember the name. He had the loft up there on Fourteenth Street and Second Avenue.

PB

Oh yeah, Larry Rivers.

SC

Yeah. ‘Cause I remember hanging out at Danny LaRue Johnson’s place and Larry Rivers was there. Larry had that show [Some American History (1971)] with the de Menils in Houston before you. He showed a bunch of images from the 1920s of black folks being lynched down in Houston. I never understood why he did that. That show was a huge disaster, and that’s when the de Menils decided to contact you to curate a show for them. Joe Overstreet was involved with Larry’s show, wasn’t he?

PB

I really didn’t pay much attention to Joe Overstreet. I know his wife, Corrine Jennings, gave me a show at her Gallery [Kenkeleba Gallery in ‘91 and ‘93] because it was the only place that would show the sculpture that I was trying to make. I was making large steel sculptures at the time.

SC

So you curated the show for the de Menils in Houston, called The De Luxe Show. How did you decide who you were going to show? I remember you called me up and you wanted me to write the catalogue essay. That’s how I met Clement Greenberg.

PB

I looked for anyone who was painting and making good, hard abstraction. When I say the word “hard,” I mean artists who were making abstract art and who had suffered to make it; living in poverty and so forth—black and white artists alike.

SC

Mm hmm.

PB

I felt in order for it to be relevant in the arts society there had to be some master painters or prominent people in Color Field painting—abstract painters. Let’s put it that way.

SC

Yeah.

PB

And Greenberg didn’t even know I painted pictures until I went to Emmerich.

SC

Are you serious?

PB

I never told him I was a painter.

SC

Now, how did you make the contact with Emmerich? Now we’re shifting back to that.

PB

I think that was done through Noland or Greenberg, I’m not sure. I know André Emmerich had no interest in showing me as a black artist. He was only concerned in showing me as a very gifted artist.

SC

Right.

PB

And that’s the way it went.

SC

So, André Emmerich got in contact with you?

PB

Yeah, André called me up and asked me if I was interested in showing with him. And I didn’t even know who he was.

SC

Oh, that’s interesting. He was a big time guy.

PB

Even though I was working at Perls. I didn’t know who the hell he was at the time.

SC

Uh huh. Would Emmerich come into Perls at all?

PB

Yeah, you know… Klaus Perls was head of the Art Dealers Association.

SC

Uh huh!

PB

And Emmerich was involved in the Art Dealers Association, so I saw him all the time. But I didn’t know that he had a gallery on Fifty-Seventh Street, because once I left Perls, I didn’t want to go to another gallery. I was sick of galleries.

SC

Now, when you first came here in ‘63, you worked at the Guggenheim Museum. How long did you stay at the Guggenheim? What was your job there?

PB

I was in the installation department.

SC

How long did you stick around with those people?

PB

I was there for three or four years. I quit and went back to Detroit in 1968. And the Perls asked me if I would come back to New York City and work for them. And I had no idea who the Perls were. So, when I came back I said, “What do you want me to do?” He said, “I wouldn’t ask you to do something I wouldn’t do myself.” I said, “Well…you’re very rich. Am I gonna get very rich here?” He said, “You will always be very rich.” And I said, “Good. Thank you.” And I started working as an installer for them.

So one day I was helping the janitor move a crate at the gallery. And this woman walked up to me and asked me how much this painting was that was hanging in the gallery. And I said, “I have no idea.” So, she started talking to me, and we discussed the painting. And she said, “I wanna buy it.” And I said, “Great!” So, I went to Klaus Perls and I said, “This woman wants to buy the painting.” And he said, “What!?” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “Who, who, who, who did she talk to?” I said, “We’ve been talking for a half hour or so.” He said, “Oh really?” So, the woman told him that they should hire me as a salesman because I had such a great mind about painting.

SC

Oh, fantastic.

PB

And the painting went for $180,000. So, Dolly Perls asked me to come to dinner with them and I went. And the minute we sat down, they said, “Have you ever worked in a gallery before?” I said, “No.” And they said, “Well, how much would you be expecting financially?” I said, “The woman paid $180,000 for that painting, right?” He said, “Yeah.” I said, “That’s a lot of money! Do I get some of that?” (laughter)

SC

Yeah, right. (laughter)

PB

He said, “Of course not.” I said, “I don’t get it.” (laughter) “What the hell do I do here?”

SC

“Where’s my cut?”

PB

Yeah, “Where’s my cut in this deal?” He said, “Well, not there.”

SC

(laughter)

PB

So he said, “Do you have any clothes?” I said, “Yeah I got clothes.” And Dolly said, “We’re gonna get you a charge account at Bloomingdales.” I said, “No you’re not. I want a charge account at Meledandri. I only wear handmade shoes. And handmade, tailored suits—Italian cut…”

SC

Right!

PB

”…And shirts. I want shirts that are handmade.”

SC

Uh huh!

PB

And she said, “Who do think you are?” I said, “Who do you think you hired?”

SC

I bet.

PB

So she said, “Fine.” That was the end of it.

SC

(laughter)

PB

So, that persisted for seven years through Europe and America. And of course I got into enormous trouble at different times that they got me out of. At a hotel one time, I rang up an enormous bill. It was at their private suite that they kept year-round, at the Royal Monceau Hotel. It was like $6,000 a week, something like that. I had a good time… They paid for everything, no questions asked.

SC

Now, who was this woman who seemed to be super rich then? You remember that dame?

PB

Oh yeah, Mary Frances Rand. I met her at Perls. She was the heiress to International Shoes in St. Louis.

SC

I think I met her through you.

PB

Yep. You did. Everybody black met her. I introduced her to everybody I knew that was intelligent and black. She collected my work, and later when she died, she left me all her childhood photographs. She died in 2011.

SC

Now, how did I meet Simone Swan? Did I meet Simone through you, too?

PB

Simone Swan came through John de Menil.

SC

And what is she doing nowadays?

PB

I don’t think she’s still alive. She was the founding director of the Menil Foundation. She collected my work also. She donated one of my paintings to the Met in 1980 [Pink Elephant, (1970–1971)].

SC

So, she left the planet a long time ago?

PB

Mm hmm.

SC

Now let’s go back. You showed at André Emmerich at least twice uptown.

PB

Yeah, and once downtown. I showed in Zurich with him, too.

SC

Yeah, I remember you showed down at the gallery in SoHo, too.

PB

Yeah.

SC

That’s when Nathaniel Hunter “Junior” was still alive.

PB

Yeah.

SC

Now, did you sell a lot of stuff through Emmerich?

PB

According to André’s records they sold everything that he showed of mine. He was quite a guy, André. We had one falling out because of Noland’s wife Peggy Schiffer. She told me, “Don’t show downtown. Only show uptown.” This was maybe 1973. And André said, “I’m trying to show you downtown. You’re the one we’re trying to show downtown big time.” I said, “I don’t want to do it.” So, I missed one show with him. I eventually showed my last show with him downtown.

SC

I see. I remember sitting in your studio on Broadway with you one time, and Clem Greenberg was sitting there, drinking scotch. You were preparing for a show at Emmerich. I think I was writing something about the show, and Ken Noland was there, too. And you were doing spray painting at the time. You were spray painting on a ten-by-thirty-foot canvas on the floor. And you guys hung this large canvas on the wall and starting taking stuff off, “Edit this out, leave this in, and edit this out…”What you guys were concerned about was whether there was any shadow or semblance of a human figure on the canvas, and if so you would cut it out. You would keep the best parts, frame them, and then throw away the rest.

PB

Right.

SC

And that’s where you made those spray paintings.

PB

The only problem I ever had painting was the difficulty, physically, of getting the paint out of the jar and onto the canvas. The spray gun showed me how to do that quickly. Before Perls, I was working for Rambusch Decorating Company. I had to paint two gallons a day, seven feet in the air. I painted all night. That’s when I started losing my shoulder. It slowly started to deteriorate from there. And that was the end of it.

SC

Now, let’s go back to that show you curated down in Texas for the de Menils. What was your experience working on that show?

PB

That was a very strange situation. I don’t know who put it out, but a rumor came out that I was scheming to steal everyone’s art. And Ken Noland had to step in and handle it.

SC

SC

They accused you of stealing people’s art?

PB

They said I was planning a major scheme to steal everyone’s art. People said Michael Steiner started the rumor. I don’t know why.

SC

Oh God!

PB

They weren’t doing me any favors. Noland put his own Olitski in that show because Jules Olitski and I could not make it as friends. And then Larry Poons came in and Dan Christensen behind him. Michael Steiner came in at the end. They all fell in line after Greenberg came on board. I have no idea what Noland and Greenberg did, but they squashed whatever the problem was.

SC

I see, yeah.

PB

It was like a museum show. They had to handle things the same way: fill out an application to send the paintings in, and paperwork to send them back out—all kinds of stuff.

SC

Right. You made it very professional.

PB

To this day, I don’t know why the show is held as one of the greatest shows of its time. I guess because it was the first exhibition that had first-class abstract painting in it.

SC

Well, what I admired about it, more than anything else, Peter—I remember when you came over when I was living on East Third Street. You walked in and said, “Guess what Stevie? These people asked me to put together a show.” And what I admired was your courage—you didn’t make it a black show.

PB

Yeah, I couldn’t do that.

SC

Because those people were busy talking about black this, black photography, black music…

PB

I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t do that. I wanted to have an integrated show.

SC

You went the other way. You made it multicultural. I said, “Goddamn!” Now, did you get any flack from the black community because of that?

PB

Oh, of course! I don’t want to mention names, but there are several black artists that would like to shoot me today because they weren’t in that show. Some of them are dead, but the ones that aren’t dead still give me a lot of bullshit every time I see them.

SC

Well now, how did you meet Nathaniel Hunter “Junior”? And how did you guys become friends? Because I met him with Chester Wilson at Saint Adrian.

PB

I met him before then. I met him at the Drone? Something like that, on Eighth Street. What’s it called, the Dome or the Drone?

SC

Oh, I know that joint. Yeah.

PB

I met him in there. And I realized he was a very unique individual. He made me laugh.

SC

He made me laugh too. He made everybody laugh. (laughter)

PB

And he spent twenty-five years in my house from eight o’clock in the morning to three o’clock in the morning every night.

SC

I know, I know. (laughter)

PB

And he drove every girlfriend I had away.

SC

I know. (laughter)

PB

And when he died I said, “That’s enough. I’m not going to his funeral.” I don’t go to funerals. I didn’t go to my mother’s funeral. They’re too much for me.

SC

Now, tell me this now, in terms of your art, when you started showing your work at André Emmerich and places like that, why did you decide to go into abstraction and Color Field, as opposed to figurative or anything like that? Had you done a lot of figurative work as a young man?

PB

I painted a lot of figurative paintings as a kid. And this was another way to look at things, as far as I was concerned. And this term “Color Field,” I never knew what it meant. I still don’t know what it means. And I don’t know if I’m part of that school or not. If I was part of that school, someone should show me.

SC

Yeah, Clement Greenberg labeled that, you know. He came up with the title.

PB

I had no idea.

SC

Why do you paint Color Field art instead of figurative or representational work?

PB

I knew this guy from Detroit who painted surrealist, figurative paintings, and they were interesting to look at for a half hour or so, or twenty minutes. But then after that—there was nothing going on for me. I just didn’t understand it. It’s just like how I don’t understand all this black art that’s going on now. Doesn’t make much sense to me to make “Aunt Jemima,” or whatever that Kara Walker piece was [A Subtlety (2014) at the Domino Sugar Factory in

Brooklyn]. I don’t care about that. I’m not interested in that kind of look of things. And I’ve been accused of being anti-black or whatever. But that’s not true, and you know that’s not true.

SC

I know that’s not true.

PB

Maybe it’s because I’m not easy to be around. I’m not comfortable around a lot of people. I know that.

SC

Well, I know that the de Menils held you in high respect, high esteem. They thought the world of you.

PB

Well a lot of very wealthy and important people felt that way. But I don’t get that attention from the Studio Museum in Harlem, for instance. I don’t get any attention at all from any black situations coming my way. The only black woman I know that’s ever paid any attention to me in New York City was Halima Taha.

SC

Now, when did you get that place upstate? I can’t remember that either.

PB

I’ve had it twenty-six years now. It’s in Saugerties, New York. I’m there most of the time now.

SC

Now, have you been showing of late? And are you still getting your stuff collected all over the place?

PB

People are still collecting things occasionally. But I haven’t had any shows, no.

SC

So, what kind of stuff are you doing now?

PB

I’m just painting, and making sculptures, too.

SC

Oh, fantastic.

PB

I’ve never stopped working, you know. Regardless of what goes on.

SC

What kind of material are you using for the sculpture, just metal or wood?

PB

Steel, very thick steel, some of it’s thin, yeah. Stainless steel, mild steel, brass…

SC

And it’s abstract?

PB

It’s abstract, yes.

SC

And how are you doing physically, in terms of moving all that shit around with your shoulder? I know you dislocated it not too long ago while you were driving your tractor over a tree stump.

PB

I can’t really work without someone helping me. My grandson helps me sometimes. And I have another guy that helps me too. There’s a big tractor that comes in and does the heavy lifting.

SC

Now, do you ever run into any of those people we know, William T. Williams and David Hammons, and all those other artists that were around back in those days?

PB

No, we haven’t kept in touch since I lost the firehouse in the early ’80s.

SC

Oh that’s right the firehouse. That was your place on Lafayette. What’s the story with that?

PB

The city just didn’t want me to have it. It was a national landmark, and they went after it in a very strange way. My Chinese landlord, Thomas K. Wong, gave me a lifetime lease for $500 a month. The city went after him for being a crook in Chinatown, and as a result they evicted me and my family and gave the entire firehouse to Jon Alpert and the Downtown Community Television Center.

SC

Oh, Jon Alpert from downstairs?

PB

Yeah I had the whole top floor and he took it from me. I let it go because my daughter Garrett Bradley had just been born.

SC

Yeah, I remember. But before that happened you were teaching at Franconia College in New Hampshire. This was after you left Perls. I think it was 1975 and you invited me and that goddamn, crazy Jose Fuentes up to that school. How did that teaching job come about?

PB

That came through Noland. They wanted Noland to teach at Franconia and Noland said, “Peter Bradley should teach here.”

SC

Oh, I see.

PB

And so, I went to Franconia and Leon Botstein, the president, hired me. I don’t know, begrudgingly or what. But he hired me.

SC

He was a young man then, yes. And now he runs Bard College. Did you get along with him at all?

PB

Yes, I did.

SC

Yeah, all I remember is coming over to visit with Jose Fuentes, and I gave a little lecture on jazz up there. Now, you were teaching them abstract art, weren’t you?

PB

Right. Abstract painting.

SC

The building that Jose and I stayed in when you were in New Hampshire—you told me Jack Tilton owned that building. Is there any truth to that?

PB

Yeah it is true. It’s Tilton’s building. It was on the main street of Littleton, New Hampshire.

SC

I think you told me you threw Jack out of the goddamn building.

PB

I did. That’s why I don’t speak to him till this day because he came to me and said, “Where did your money come from?” I said, “Who the fuck you talking to?”

SC

I hear you.

PB

“‘Where’s my money come from?’ You ask any other artists where their money comes from?” You see, he was coming off racist to me and I didn’t like it.

SC

You threw his ass out.

PB

I told him to get out of my house. It was his building, but I was renting that apartment.

SC

So, how long did you stay at Franconia? Because that school closed down after you left, didn’t it?

PB

Yeah, it did. I taught there for two years, from 1974 to 1976.

SC

So, how did you like it?

PB

I thought it was great. If it hadn’t closed, I think I would have never come back to New York City. I’m not crazy about Manhattan, you know. I like the country. Manhattan’s got too many games going on. (laughter) The hell with it, you know what I mean? I’m not crazy about the city.

SC

(laughter) Well, how often do you come down to the city?

PB

This is the first time I’ve been here in two months.

SC

Now Peter, you gotta tell me something: How did you get Miles Davis’s horn?

PB

Which one? The blue horn?

SC

Yeah, how did you get it?

PB

Kenneth Judy bought it for me. Kenneth Judy is a dentist who’s collected my work for years.

SC

Oh, you’re talking about when they had that auction of Miles’s drawings and stuff at Lincoln Center.

PB

Yeah, I went to the auction. David Hammons bought some of Miles Davis’s drawings.

SC

(laughter) Oh yeah, I remember that. And you know what he did? They asked David to be in the 2006 Biennial and he put Miles’s drawings in the show instead. Now, Peter, how in the hell did you get into Yale? How did that come about?

PB

Jack Tworkov came and begged me to go to Yale.

SC

What year was that?

PB

I don’t know, ‘65, ‘66. I dropped out a few years into the program.

SC

And where were you living at that time?

PB

I was living on 103rd Street. No, no! I was on West Sixteenth Street and Seventh Avenue. Next to Blackburn’s—

SC

Oh, Bob Blackburn.

PB

Yeah, next door to his printmaking studio. I was there. Tworkov couldn’t stand the fact that I had a white girlfriend. It drove him crazy. He just couldn’t handle it. And then he tried to fuck me over at Yale. He was saying I couldn’t have a Ferrari on campus, while my white roommate had a Jaguar. He said, “He lives on Fifth Avenue, that’s another story.” And I told him, “Hey, listen man, I painted with you when I was eighteen years old. What is your problem? I don’t get you.” He couldn’t say anything back to me. And then I said, “I’m going to leave Yale and I’m going to prove to you that I’m probably the best student you’ve ever had. I’m the best of my peer group at this university.”

SC

So, William T. Williams was up there at that time?

PB

He was up there, yeah. He was walking around being the person they wanted him to be there—for black people.

SC

Yeah, right. (laughter)

PB

Tworkov told me if I got rid of my Ferrari, he’d give me a degree. I said, “Fuck you!”

SC

(laughter) Now Peter, does your love for jazz come out when you get in front of a canvas? Do you use some of the things you know about music and apply them to your art-making?

PB

Well, sometimes I’m consciously making a move with color and it might have a sound to it, against another color. So, I’ll either stop and go, or go around or embellish—something like that. Also I paint for myself. I don’t paint for a movement.

SC

Do you listen to music while you paint?

PB

I used to.

SC

And why did you stop?

PB

The studio is a long way from my house and it doesn’t have electricity right now. (laughter)

SC

Oh! Well that’s reason enough. Let me ask you the same question in a different way. When you are standing in front of the canvas making a piece, do you hear music in your head?

PB

No.

SC

So, what do you focus on when you paint? The colors and the composition?

PB

I’m not quite certain. I mean, it’s just something I’ve done all my life. It’s like going to work, like you writing a letter or something. It’s about a message I wanna try to get out that day. I don’t think about it any other way.

Peter Bradley & Quincy Troupe

Quincy Troupe

Okay Peter, I want you to tell me the story of your childhood again. I know you had to be born somewhere around 1940. I realize that you were adopted and you don’t know who your father was—maybe you do, maybe you don’t want to tell anybody. (laughter) But start from there and just fill in the blanks. Tell me what you know; for example, Miles Davis said his earliest memory was when he was trying to touch the goddamn flame from the stove and almost burned his ass. So, tell me about your earliest memory.

Peter Bradley

It’s this foster brother I had named Perry Wright. He later became a doctor and lived in Owen Hills, Jersey. He must have passed by now, I don’t know. But anyway, he taught me how to tie my shoes.

And he said, “Once you know how to tie your shoes you can break any knot in the world.” My adopted mother’s name was Edith Ramsey Strange. She was born in 1888, and raised in Roanoke, Virginia. She was a beautiful woman; well-dressed, and she kept a hundred dollar bill in her stocking at all times.

QT

Lord. What did she look like?

PB

She had pure white curly hair, similar to mine. She was about the color of this wine cork, a little bit darker. There are some great photographs of her, too. I just found one of her with my Jaguar.

She worked for this very wealthy family from Chicago. I wouldn’t say she was a maid exactly, but she was something different. Meanwhile, they set her up in this house that was designed for the engineers of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad. The guy she worked for was just some rich white guy who lived in the town. He had a large property. The house we lived in had twenty-seven rooms and it overlooked the Youghiogheny River.

QT

What’s the name of this town?

PB

Connellsville, Pennsylvania.

QT

Where is that exactly?

PB

Just outside Pittsburg. It’s the hometown of Johnny Lujack.

QT

The quarterback from Notre Dame?

PB

Yeah, and the hometown of that fellow who ran the 500 meters at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, Germany.

QT

Mal Witfield?

PB

No, John Woodruff. Same town. And Harold Betters from the Betters Band, is from there. Anyway, this rich white guy made it possible for my mother to buy this twenty-seven-room house and then she went right to business.

QT

He must have liked her a lot. What was his name?

PB

I forget his name, but he was part of the Capehart family from Johnstown, Pennsylvania. That man liked my mom a lot. But she said she just didn’t have time for sex. She only had time for money. She was very serious about money. She went to the state and in a period of thirty years she had sixty-four foster children in that house. And she got some good money for each one of them at the time. She also monopolized all the sweat-work in the town. She employed all the janitors for all the movie theaters: there were three of them. My mother had enough influence to have the all-white drugstore hire my foster sister for two hours every Sunday afternoon. She was probably one of the most successful women of color in that town

along with Harold Betters’s mom. My mother ran a jazz club from her house, so a lot of major jazz musician came through when I was kid. She picked up the jazz bands, too.

QT

She picked them up? At the train station?

PB

Yeah. They were all coming through there you see, on the way back to Chicago, from Philadelphia, leaving Pennsylvania. They didn’t go much to the South.

QT

Did she have a car?

PB

She had a Buick Roadmaster and later an Oldsmobile. But she never drove. Bradley drove.

QT

Who’s Bradley?

PB

Bradley was a waiter for the Baltimore Ohio railroad. His name was William Alexander Bradley III, which makes me the forth, technically. Because he worked for the Baltimore Ohio railroad, he would give me train passes to go anywhere I wanted to, anytime. I went to California by myself when I was maybe fourteen years old.

QT

Wait, let’s go back. You went to California by yourself when you were fourteen? What made you want to go to California?

PB

Because I could! I wanted to see what it looked like. I saw those Lone Ranger movies and stuff like that. I wanted to see if that shit was real.

QT

So you wanted to see Hollywood?

PB

I didn’t know the Lone Ranger had anything to do with Hollywood. I didn’t even know what Hollywood was at the time. I thought he was out there for real, riding around on the range. I thought I might see that dude on the train.

QT

Oh, you thought he was real? (laughter)

PB

Yeah. Same thing with Flash Gordon; that’s what got me interested in planes I think. ‘Cause he had all those rocket ships. And you know when you draw rockets, things that are pointed, they can be sitting on the ground or in the air, you know it doesn’t make much difference. It makes the same statement.

QT

Is this in Los Angeles?

PB

Yeah.

QT

So what did you do?

PB

I walked around and called my mom every day. She would wire me money at Western Union.

QT

So you walked around, what did you see?

PB

Well, I really went to go see this girl. Her name was Gloria Maise and she lived at 1410 Golden Gate Avenue in San Francisco. I made a mistake. I went to LA and I didn’t get to go up to San Francisco. (laughter) I never found out where the fuck she lived at.

QT

You were supposed to go there?

PB

Yeah! She said, “Come to California,” you know. I was in Western Pennsylvania. She was a Katy Keene pen pal. That was way before computers.

QT

She was a what?

PB

Katy Keene was an Archie Comics character; she was a model and a fashion designer. Kids would submit all these little drawings of clothing for Katy Keene to wear. If your drawing was chosen they’d put it in the comic and place your name at the bottom. It would state that it was designed by such and such person and your address as well—you know, pen pals.

QT

Okay, so you went to LA looking for her?

PB

Yeah. Not really looking for her, I just thought maybe I’d find her. I just thought California is California.

QT

Let’s go back to Mr. William Alexander Bradley. Let’s talk about him a little bit.

PB

He was from Columbia, South Carolina and he had two sons. I think one of them went to Howard University.

QT

What did he look like?

PB

He had thick hair. He wasn’t conk-headed at all. His hair was waved up—had natural wave on its own. He was short. He smoked cigars and he was very smart. He was a player to a certain extent. And my mom married this fool—that’s what she called him, a fool—and I got a last name.

QT

Do you have any angst about who your real father was?

PB

No. I never did. Do you know the Miles thing with my adoptive mother’s brother?

QT

What do you mean?

PB

Miles Davis used to come to Western Pennsylvania. My mother knew him ‘cause he used to come there with Errol Garner, the jazz pianist. And something happened one day. I wasn’t even in the house. I was a child. I was out playing somewhere. We got to the dinner table: my mother, my uncle, myself, and all the other adopted children. And my uncle Tom, my mother’s brother, would sit at the table and just start eating. (chewing sounds) He told me, “You look just like that ugly black motherfucking father of yours that’s in the other room over there.” And my mother picked up a dishcloth. Bam! Hit him in the face with it. Almost knocked him out ‘cause he was drunk all the time.

QT

A dishcloth?

PB

Yeah, she kept a dishcloth. She hit him and knocked him off the chair. He was drunk all the time. He was making that cheap ass wine and drinking it day and night.

QT

So he was talking about Miles Davis?

PB

Yeah, Miles was in the house at that time. I didn’t know.

QT

But he said that Miles was your dad?

PB

That’s what he said. And I didn’t pay much attention to it, because I didn’t know who Miles was at the time. Didn’t make much difference to me. So when I came to New York City for the first time by myself, my mother gave me a note and said to take it to this address and tell him that you’re looking for a place to live. So I did.

QT

He lived on West Seventy-Seventh Street.

PB

Yeah. I went to The Met first. I had this little blue suitcase with a star on it. And my mom told me to always put my money in my socks. And she said, “If your suitcase is terrific people will leave you alone. They’ll know that you have some stature.”

Anyway, so I go to Miles’s apartment and I knock on his door and this little woman comes to the door. She said, “What you want?” And I said, “Oh, oh, here,” and handed her the note. She took it and Bam! She slammed the door in my face.

QT

How old were you then?

PB

Twenty-two.

QT

So this was like 1962.

PB

Yeah, exactly around that time. So I walked away. And then I hear this strange voice—I’d never heard Miles’s voice in my life before; it sounded like some frog. “Come back here now!” So I go back to the doorway and he says, “Come on in.” So I went inside his house and he just sat there and stared at me. He asked me one question: “What are you doing here in New

York?” And I said, “I’m looking for a place to live.”

Now, I found a place to live, but it was too much fucking money. It was across the street from The Metropolitan Museum. He didn’t say anything for a while. He just stared at me. (laughter) So then he says, “What’s the story with this other place?” I said, “Well, this woman walked up to me and said her husband had died a couple weeks ago and that she needed some help. She has a room and she would give it to me for $400 a month. I told her to go fuck herself ‘cause I’d just come from studying at the Society of Art and Crafts in Detroit where we had a house on Web avenue—big as a motherfucker—and the whole place cost $300 a month.” But it was a hip apartment in the right neighborhood. I just thought the price was crazy because I had never paid rent in my life. And Miles told me to go back now and get it. “Go back now!” So I ran back there, two days later, and got the apartment.

QT

So okay, I want to get back to this whole thing about Miles and you. ‘Cause he and I had known each other a long time, so what you are saying is that because the guy said, “That’s your daddy,” it put a seed in your head?

PB

Right, “Your ugly black daddy.” ‘Cause at that time Miles was considered ugly.

QT

He was dark as hell, I know that.

PB

Very dark. “Little Dark Davis,” that’s what they called him in Detroit.

QT

Well, in St. Louis they called him “Little Dark Fauntleroy,” after that book by Frances Hodgson Burnett, Little Lord Fauntleroy (1886).

PB

I’ll tell you something very interesting I’ve never told anybody else in my life. There was this woman. She was an albino and she lived near us in Pennsylvania. She was a black albino and she was crippled. She had straight, long hair, and freckles. That was her shit. (laughter) She assumed that she was white. That was it.

She said to my mother, “Edith, as pretty as you are, why would you adopt the ugliest little black baby in the world?” And my momma told her, “No this is the most important little black baby in the world.” That was the end of it. I never asked for anything. Mother gave me everything I ever wanted.

QT

Now let’s segue a little ‘cause I wanted to get your thoughts on Basquiat. When I saw Basquiat on the front cover of the New York Times Magazine in 1985, Miles called me and said, “Who is this motherfucker on the front cover?” “Motherfucker, you think I know?” That’s what I thought in my mind, ‘cause I knew a lot of people. I said, “I don’t know shit, I’m trying to figure out who the fuck he is, too.” You know what I mean? So after I saw that photograph, Margaret, my wife, and I went down to see his work. We went to the Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat Paintings show at Tony Shafrazi Gallery with some friends of mine and this architect from St. Louis. He told me he hated Basquiat’s work. And I said, “I don’t hate it.”

PB

There’s nothing much to like, but I don’t hate it either.

QT

I said, “This guy is doing what he is doing and this guy is going to be really big.” It had something to do with his art and his personality. Here comes a motherfucker who’s younger

than you, sitting up there with a suit on. And to think he became the shit, by making primitive work and people are in awe, is incredible. That’s why people got all fucked up about Basquiat becoming famous, especially in the art world. Black painters got all bent out of shape.

PB

And the dealers took over and most of them were assholes. They weren’t real dealers. Leo Castelli was a fucking advertising agent. André Emmerich was the only real art dealer. People don’t know what they want, I tell them what they want. They don’t know any better. That’s how I got successful.

QT

Well, we got closets full of books on Matisse, Cezanne, Picasso; we got the whole history of painting in the back room.

PB

Do you have Picasso by Christian Zervos? It’s a serious volume of books documenting almost everything Picasso has ever done.

QT

No I ain’t got that.

PB

It costs thousands of dollars. It was in my hands because I had to read it every night when I worked for Perls.

QT

Let’s talk about the house that you lived in in Pennsylvania, and everybody coming through there.

PB

Yeah, it sat on top of a hill.

QT

Describe that.

PB

The address was 127 Witter Avenue, Connellsville, Pennsylvania.

QT

How far was it outside Pittsburg?

PB

Connellsville? Sixty miles. I used to sit there and watch trains and locomotives, as big as this block, go up to the mountains. It was unbelievable.

I would sit on top of the hill closest to my house, watching. I was amazed. They were so big, and made all kinds of sounds. They could go up steep hills. Then there was this whole engine house, all stone with all kinds of steel in it. They worked on trains all day and all night. All the black guys would be in their cars at five in the morning going to Pittsburg, working in steel mills. Funny shit.

QT

So it’s really in the country. How big was it?

PB

I don’t know because black people stayed in one section mostly.

QT

(laughter) Ain’t that normal?

PB

Right, that’s what happens.

QT

So tell me about the people who came through your house when you were a kid. Who were the musicians that played at your mom’s jazz club?

PB

Clifford Brown, Max Roach, Alma Jamal, Fred Jones, and Art Blakey of course—they all came through.

QT

Miles?

PB

Miles, The Turrentine Brothers…

QT

Stanley and Tommy?

PB

Yep. Everyone came through to see her!

QT

They liked her?

PB

They liked her and they liked the way she was able to make money. She was able to start a black enterprise before anybody else in Western Pennsylvania.

QT

So you grew up around those kinds of musicians and artists, right? So tell me about when you first started to draw.

PB

From day one. My momma would come upstairs and she’d say “Pete, turn on the radio.” And I’d turn on the radio and she’d sit in a rocking chair. She would read the New York Times and she’d have The New Yorker, too. I’d look at the cartoons in The New Yorker. She’d say, “Well you can draw, too. Okay, get to work.” And I would draw her every day.

QT

Your mother?

PB

Yeah. And she said well “I’m going back downstairs now, take care.” I never really left the room. I didn’t want to go outside. Then she said, “Why don’t you take a sleigh ride?” I’d say “Okay,” go outside take a sleigh ride and come right back in. Fuck the sleigh ride, ‘cause in Connellsville the hills are very steep. You could kill yourself.

QT

Now, you were telling me the other day a story about Joan Mitchell. Can we go back to that?

PB

Yeah, we were in France: Snuff, Mary Frances Rand, and me.

QT

Ed “Snuffy” Clark?

PB

Yeah, we went to visit Snuff at Joan Mitchell’s place. And Joan Mitchell was acting nasty to me, which she should not have done. She should have known better than that. And meanwhile we came to visit Ed Clark. Joan Mitchell was married to Jean-Paul Riopelle at the time. He was a Canadian painter. Anyway, she got very upset with me.

QT

Why? Was it about race?

PB

Could have been, I don’t know. She asked Mary Frances, “What’s your name?” And Mary goes, “My name is Mary Frances Rand.” Immediately, Joan yells, “You’re a liar!” In other words, “What are you doing with this nigger if your name is Mary Frances Rand, the heir to International Shoes in St. Louis?” So she ran into the house and looked up her social registry, came back, and was very friendly with us. And Mary Frances said to me, “It’s time to go. We’re going to Calder’s house.” And Joan goes, “Can I go?” And Mary Frances said, “Well, ask Peter.” And I said, “Who are you?” And then we left. That’s my Joan Mitchell story.

QT

Amazing. Now Peter, what makes a bad painting and a good painting for you?

PB

I don’t know…maybe an articulation of what you’re trying to do, see, and how you promote it—and if you promote it honestly. Honesty is the best way to see it. And how you use color. Other than that I don’t know.

Everything you see, when you look out the window, the color is set up right. When you see butterflies, when you see humming birds, anything you see in nature the color is set right. It’s a code, but we don’t know what the fuck the code is.

QT

What do you think the code is?

PB

Who knows! Could be danger, could be love, could be anything… but it’s beyond a vocabulary that we can understand.

QT

So it’s a mystery.

PB

I think so.

QT

So you think great paintings are like that: a mystery?

PB

Yeah.

QT

Tell me, who are some your favorite painters?

PB

The Italian painter, Paulo Uccello—the color in his paintings is outrageous. And there’s a whole lot of movement going on at the same time. Horses that look like they’re going forward,

but they’re standing still. I mean great stuff. But black people invented abstraction, whether people want to believe it or not.

QT

Tell me why you say that?

PB

Because everything we do is abstract. The art that we make is abstract. Abstract art is a very special thing that means something to us. But Picasso and Braque jumped up on it with Cubism. They didn’t know shit about abstract art before that.

QT

You like Picasso and Braque?

PB

Yeah I like both of them. And Braque was a nice guy. He smiled and shook my hand. Frank Perls said to Picasso in French, that Picasso and I look alike. And Picasso says, “No he looks like Soutine.” But Merton Simpson said I was the black Picasso. (laughter)

QT

Merton Simpson said that. I didn’t know him well, but I knew him. You respected him?

PB

Yeah. Major art dealer. Didn’t know him very well, but I have a lot respect for him and what he did. I don’t know how good of a painter he was, but he was a great dealer.

QT

Who are the African American painters, going back and going forward, that you think are important?

PB

I think that David Hammons is pretty much carrying that line, you know, “I’m a negro. This is what’s going on…” And I like it, but I don’t wanna be involved in it. I just wanna paint and step outside of the politics behind art. The politics are always there, but I don’t want it to be the subject of my work.

QT

What about William T. Williams?

PB

As a friend, I’m worried about William.

QT

Why?

PB

Because he deserves more recognition. He’s a great artist. I’m gonna tell you a funny story about William T. Williams. One day he came to me and said, “Peter, Rockefeller is coming to my studio to see my art.” We shared a studio together. I said, “Alright Will, that’s cool with me.” Rockefeller came.

QT

David?

PB

Yeah. I used to see him at Perls all the time. I brought a painting to the studio, a 1919 Cubist painting by Picasso. I brought it home to look at, because I had to sell it in two or three weeks to someone important, so I had to study it. And William T. Williams is showing his paintings

and on the way out the door David Rockefeller looked at the painting and said, “Beautiful reproduction,” and walked out the door.

QT

Why did he think that?

PB

What do you mean? He sees a Picasso in some nigga’s studio, he’s not gonna think it’s real. It couldn’t be for real.

QT

But it was?

PB

Yeah!

QT

(laughter) That’s fabulous. Let’s go back to Basquiat. What did you think of his work?

PB

He came to my studio on Broadway a couple of times. We talked. He showed me what he was doing, and I said, “It’s great, keep on doing it.” There were a lot of black artists at the time selling art on the street. I think David Hammons was one of them.

QT

Yeah he was. Did you think Basquiat had any weaknesses?

PB

I wasn’t thinking about any of his weaknesses, I just wasn’t interested in what he was doing.

QT

You weren’t interested at all?

PB

His paintings don’t interest me. I mean, I like them to a certain extent, but I didn’t pay much attention to him. I’ve been a huge proponent of Ken Noland’s work.

QT

What is it about his work that you like?

PB

It’s all about color. Fuck the bullshit. It’s all color. A painting can be broken down to the simplest forms—just like that. And that’s what he did. And it got cleaner as his work progressed. It’s broken down to sixteen colors. Color can create anything you’ve seen before. But I was not a color-straight-down-on-the-canvas type of guy. I was more emotional. And Noland told me before he died, last time I saw him, “Peter you have an opportunity. You’re one of the great painters of your time. Don’t let it go.” That’s the last time I talked to him. I took his advice.

QT

So what happened to you after you lost the firehouse? That’s when I lost track of you.

PB

I was in the streets after that. I would go to the crack houses so I had a place to sleep. I was never homeless in my life; I didn’t know what it meant to be homeless.

QT

So you started going to crack houses?

PB

Yeah, I had nowhere else to go. I was with my boy Levy Moore. Yeah, we would get high as a motherfucker.

QT

How long did you do that for?

PB

I think two years. I think I lost the firehouse in ‘89 and then I got clean and went on tour with Blakey in ‘91.

QT

So you were looking for the pipe?

PB

I was looking for something to wrap this shit up in. The pipe was something.

QT

So that’s when I lost track of you because I didn’t know where you were.

PB

Neither did I.

QT

And then after that you went on the road with Art Blakey. What were you doing with him?

PB

Handling the money and telling him what he couldn’t snort. “This is dangerous, don’t touch it. What are you doing?”

QT

Did you know I used to manage Hugh Masekela?

PB

I didn’t know that. I talked to him in South Africa.

QT

I just saw him. But I used to do the same thing. I handled his money, because he thought I was good with money.

PB

Blakey said because he knew my mom he could trust me.

QT

What did he think of Miles?

PB

He didn’t like him that much. He didn’t care about him.

QT

Why?

PB

He never said why. Boo [Blakey] didn’t care about anybody.

QT

He was cold.

PB

Yeah, he was. He liked me though.

QT

You introduced me to him in Los Angeles once.

PB

Oh, I don’t remember that at all. I could have died if I wasn’t smarter. There was so much dope. I mean that’s why he had me around. There was so much dope. And meanwhile, I’m in Paris with this fool, Blakey, in a hotel room asleep, and he’s creeping on the floor. (laughter)

QT

He’s creeping on the floor?

PB

He grabbed my leg, thought I was some girl. He was crazy.

QT

Let’s talk about color? What is the strongest juxtaposition of color for you? What makes a painting great? Tell me. Describe.

PB

I’m trying to get the shape of you. I’m trying to get the shape of what I’m looking at through this window. I’m trying to get the shape of music, I’m trying to get the shape of love. And the sound is more important. Sound, to me, created color and light. The thing that interests me the most is how color dictates sound, feelings, the whole bit, it’s all there. It’s all color. Ed “Snuffy” Clark has a lot of red in his paintings. There’s a lot of anger there. I mean, you could see it. It’s how he expressed himself.

QT

What you think about Sam Gilliam’s work?

PB

I like Sam. I promoted Sam early.

QT

What do you like about his work?

PB

He came out of the Washington School with Noland and all of them, but wanted to stay under the wall. I told him to get his hand off his art. He’ll tell you that. Take your hand out of it and make it go somewhere else. And he did it. He started doing drapes and stuff. I like Sam. Myself, I just paint. I don’t worry about anything else but painting.

QT

Do you start with an idea when you put the canvas on the floor?

PB

No.

QT

What is it that you start with?

PB

The color.

QT

So does the color jump in your head?

PB

Not at first. I think you have to push and then all of a sudden the color comes out.

QT

I see things in your new paintings like the sponges or whatever they are…

PB

Yeah, the sponges and stuff like that…

QT

What makes you put that in there?

PB

‘Cause it’s nature, they absorb a lot of color and they sit in space—it looks like they’re underwater or in outer space.

QT

Is that why you like living in the country? ‘Cause you want to be around nature?

PB

Yeah, I came outta that. And I was in Manhattan for fifty-eight years and I just had enough.

QT

So you wanted to go back.

PB

It’s not quite a return, it’s just what I know. It’s how to paint. The paintings I painted in Manhattan—I know what they look like, but now I’m doing something different.

QT

You think your work has changed a lot over time?

PB

I have no idea. I don’t pay much attention to that.

QT

You don’t look back at it.

PB

No, I just keep painting.

QT

So when you get up in the morning do you see color?

PB

I see it, whoa! Knocks me out in a second and I’m alive. I’ll tell you there’s something weird about this color thing that you don’t want to believe. The world can’t exist without color. Everything we look at, color is involved. And it’s weird as a motherfucker. Like the light here, it’s magnificent. You know what I mean? And it bounces off, boom, boom, boom… all kinds of shit. I mean it’s outrageous. And it’s color.

QT

You paint in a shipping container in your backyard, right? That’s your studio.

PB

Yeah. I’ve painted in some huge lofts in Manhattan. I don’t need that anymore.

QT

You don’t wanna live in New York?

PB

Never again.

QT

What do you think about Frank Stella?

PB

I think he’s a better sculptor than a painter. I mean his paintings are hip, but no one knew Bob Gordon. He’s a black guy who worked for Stella. No one talks about him. He was in the De Luxe Show. No one knows who he is or if he’s dead or alive. He set up those black Stella paintings. But no one knows that.

QT

He’s a painter?

PB

Yeah, a great painter. So much shit goes on and they don’t know about it. It’s ridiculous. I can’t put up with it.

QT

But this is everything. They want to take everything. The other night the American Music Awards didn’t have any black recipients. You know they didn’t have it. Hollywood… it’s just the way it is.

PB

It’s changing though, slowly, but we still ain’t there yet.

Peter Bradley & Cannon Hersey

Cannon Hersey

So I want to say, Peter, that some of my fondest memories as a child were of running around my father’s gallery—Gallery Hirondelle—in SoHo, and seeing your paintings and steel sculptures just towering over me. Those are very vivid memories for me. And this is in the ’80s when you started showing with my father, John Hersey, Jr., who is here with us today. This was after you were showing with Emmerich for most of the ’70s. I grew up being a huge fan of your work.

Peter Bradley

Gallery Hirondelle was extremely influential to me and my work in the early ’80s. It was the only gallery that wanted to show my work. Your father was a good friend to me and was instrumental to my career at the time.

CH

What year was this?

PB

It was about 1983.

CH

And you were working out of the firehouse?

PB

Yeah, I was still at the firehouse.

CH

And you were in and out of the city, right? You said something about Emma Lake Artists’ Workshops. Were you in Johannesburg around the same time, too?

PB

Emma Lake came right after Johannesburg, through Kenworth Moffett who was an art citric, a student of Greenberg, and was a big proponent of the Triangle artists. Moffett introduced me to the Emma Lake Artists’ Workshops. It’s a program affiliated with the University of Saskatchewan in Canada. I didn’t know it was such big deal.

CH

What was it like? Was that like a break, or a steady gig? Was it something you wanted to do?

PB

I just came out of Johannesburg and I was still freaked out by the whole experience. Then Emma Lake offered me the opportunity to go teach in Canada. And I really didn’t know much about it. But then I found out that everybody who was anybody went to Emma Lake: Barnett Newman, Ken Noland, Greenberg, Donald Judd, Michael Steiner, you name it. I was surprised. I mean it’s way deep in Canada. (laughter)

CH

So tell me Peter, how did you end up in South Africa?

PB

Well, it started from the Triangle Artists’ Workshop, which was founded by Anthony Caro and Robert Loder in 1982. Caro was a British abstract sculptor. The Triangle Workshop was meant to bring abstract artists from the US, Canada, and Britain, and later all around the world, to come to Pine Plains, New York, and just paint and exchange ideas. I would come visit occasionally to the open houses. It was a rigorous program that lasted only two weeks. In 1983 South African artist David Koloane was invited to the workshop, but because of some bullshit he missed most of the workshop. Because he was black, the South African government didn’t give him a passport or something like that. Anyway, I met David in New York City shortly afterwards through one of my students from Franconia College, Randy Bloom, who was affiliated with the Triangle Workshop as well. David and I started talking and decided that it would be a good idea to bring the Triangle Workshop model to South Africa, which later became the Thupelo Workshop. David then introduced me to Bill Ainslie, who was the director of the Johannesburg Art Foundation. Bill was able to secure funding from the United States–South Africa Leadership Exchange Program (USSALEP), and Thupelo was born, and Bill invited to me come along and be part of the program.

CH

And so South Africa for you, being from New York, what was that feeling like?

PB

South Africa was a dangerous place. You know that. For real, I mean it was no joke at that time.

CH

What year was that, ‘85?

PB

Yeah, and apartheid was still flying, big time.

CH

All I heard was you were drinking Champagne and eating caviar all up in downtown Johannesburg. That was the word on the street from Fieke Ainslie, Bill’s wife. (laughter)

PB

You know I would never drink that shit. I’ve never had a sip of Champagne in my life. (laughter)

CH

Well, she was saying that you were running around being a big shot, with the cocktails and the fine foods. You were living and working large, making big sculptures, making big art. Did you make paintings while you there?

PB

No, I painted one painting while I was there, that’s it. For some reason, acrylic paint was incredibly expensive in South Africa at the time, just outrageous. We brought some acrylic paints from the States to South Africa for the Thupelo Workshop, but we kept that for the participants of the program. I was mostly working in sculpture while I was there. Yeah, that’s when I made Silver Dawn (1985). It was a large steel sculpture that stood in front of ANC headquarters in Braamfontein that Desmond Tutu dedicated to the people of Johannesburg.

CH

So tell me more about what it was like in Johannesburg in 1985.

PB

Just pretty extraordinary. I remember me and Johnny [your father John Hersey, Jr.]—who came along as well—would hang out with Bill and Fieke and the guys that were part of the Thupelo Workshop.

CH

Yeah it was all white liberals.

PB

White liberals and a bunch of bullshit going on. I know the idea of the Thupelo Workshop was to take the Triangle model and bring that to black artists in South Africa. Bill, who is white, even started the Federated Union of Black Artists in South Africa, but he wanted the workshop to be open to all artists: white, black, whatever. The problem was that more whites participated than blacks—at least that’s what I remember.

CH

Tell me more about Bill.

PB

He was a nice man, a very nice man. I liked him a lot. One night we went out in Rustenburg—where the workshop was being held—and I thought I was in Manhattan. It was raining cats and dogs and this beautiful white woman comes up and sits down next to me at the bar. I’m talking to her big time and Bill is going crazy. “We’re gonna get murdered! Do not say a word to her. We could get killed any second here!” And I’m drinking so much vodka, I didn’t give a fuck what he was talking about. No one shot us. I could have gotten shot faster in Manhattan.

CH

Yeah that’s what I felt in Johannesburg. Everyone was talking about how Johannesburg was the most dangerous city in the world. I walk down my streets in New York and I have the same fear.

PB

I know—fear is fear. When I was in Alexandra I was a little scared. I spent the night in Alexandra with Fieke, but they put me—

CH

Fieke Ainslie was rolling down in the Alexandra Township?

PB

No, they laid me up in Alexandra to see what it looked like, what it was like. I went to the Leeuwkop Prison, too.

CH

Right, Fieke didn’t roll around there too much. So Peter, it was through you that I was able to meet [Mongane] Wally Serote, [an ANC—African National Congress—leader in the movement against apartheid and then a South African Parliament member]. At that time he had been a poet from Alexandra. And the self-taught artist Joe Manana was his right-hand man and friend. They both came out for the first event that my father and I did in Johannesburg in 1999: CrossPathCulutre (CPC). You know, when we did this poetry reading and an exhibition of my works entitled “Light.” Wally Serote read his poems and Joe Manana was there. They came there as an homage to you. And that was interesting, you know, that people were open to talking to me as a nineteen-year-old New Yorker in Johannesburg. A lot of that was on the back of your experience, and my father’s experience, too.

PB

But here’s what I find strange about South Africans: these motherfuckers will sit down and drink liquor with you, and you’re looking at them like they’ve never been to New York City. “Fool, you’ve never been outta Africa.” But in reality, these punks are in Manhattan a lot. I found out that they’re in Manhattan standing on Fifth Avenue looking around and shit. And they go right back to Johannesburg the same week or whatever, four or five times a year. Joe Manana is one of them. His son will tell you that. Someone saw Joe Manana on Madison Avenue one time looking at girls. (laughter) Everyone thought he was in Johannesburg.

CH

They got around, those guys. And the ANC is big on the streets of New York and in many countries. Tell me about David Koloane. What was he like?

PB

I thought he was a very quiet African painter that should have picked up his speed a little bit, in terms of color. He still held too close to Africa and I was concerned, because they want you to be a crafts person in Africa. You can’t be a painter. You have to make baskets and do some other shit—things on top of your head.

CH

He had a street style that was pretty robust, and he had a lot of dark coloration, for sure. But he’s eighty now and has become one of the masters of that time. He’s very well-recognized in South Africa.

PB

That’s great for him. He’s a wonderful guy.

CH

A lot of it came out of the Johannesburg Art Foundation and that community, because as I understand it, he was part of that community and then went to the Bag Factory artists residency or the Fordsburg Artist Studio, you know, through the Triangle Workshop and out of the Thupelo Workshop, too. How did that play into your experience of South Africa, or better, how did the whole Triangle Workshop period influence your work?

PB

The most important thing that I got out of it was the discipline to continue working, to be dedicated to the process. If you do enough of something, you become good at it. That’s all. If you stop doing it, you can’t be good at it. It’s the way it works. You know that.

CH

As an individual artist yes, but don’t you think it is also about who you surround yourself with and your relationship to the community? That plays a vital role to an individual’s success and

growth. I mean that’s what the Triangle Workshop was all about, right?

PB

That gets involved in appearances in a lot of ways.

CH

It’s just for show, you mean?

PB

Well, you know they promoted Modigliani for a long time because of his looks, Picasso too. (laughter) Most successful artists are handsome or good-looking. It’s an arrogant trip to be involved in. Every now and then you need all the help you can get. (laughter)

CH

(laughter) For sure. I felt like going to the Johannesburg Arts Foundation, and meeting Fieke when I was eighteen years old, was important to me in terms of being part of a creative community. I mean Fieke took me in because of you, and she exposed to me to a lot of shit. Right from the airport, she took me straight to the Leeuwkop Prison also. We stood outside waiting for the policemen to come and show us a beat-up man. We waited in the South African sun all day, the first day I arrived in Johannesburg. And… (sighs)

PB

But you wanted to go.

CH

It was intense. But I went because you were playing it up hard. I was coming from a Western European perspective—I’d just biked from Vienna to Paris prior to going to South Africa—I was outside my comfort zone. You basically told me I hadn’t seen anything yet and that I should go to South Africa. That changed my life.

PB

South Africa changed my life, too.

CH

And I think it must have done that for a lot of different people. I mean, encouraging people to take new steps towards freedom. And that’s the thing that inspired me. South Africa became a second home where I went fifteen times over a ten-year span. At the time, there was a feeling that the country had a fresh look forward. But I haven’t been back for ten years now.

PB

Well, now you’ll get a fresh look at it.

CH

How long has it been since you were there?

PB

Since 1990, I think. Yeah, I worked in another workshop at the Alexandra Arts Centre in 1990. I don’t remember South Africa having any problems with painting. That’s the first thing I saw. I just had trouble with them spending so much time on something that didn’t mean anything. Like this one guy, this sculptor, I forget his name. They introduced me to him. He was making this cow. And the cow was perfectly, anatomically done out of clay. And I said, “How long you’ve been doing this for?” He said, “Well, two years.” I said, “What the fuck are you doing for two years? What are you doing when you come in every day?” He stands there and does this every day? What the fuck is that? His whole mind is trapped up in this shit.

CH

(laughter) That’s because you’re a speed painter, Peter. You have the weapons of the industrial age for your art-making. Not everyone sprays the paint like you, right?

PB

I haven’t sprayed a painting in years.

CH

What? You were spray-painting down on Green Street, across from Tony Goldman’s office in that basement studio there.

PB

That was twenty years ago.

CH

That’s less than twenty years. That was like 2002, 2003.

PB

How many years ago was that?

CH

Fourteen.

PB

That’s a long time, that’s almost twenty years. (laughter)

CH

Tell me a little bit about your experience with Fieke in Johannesburg.

PB

She was a terrific lady. She was. When I got there I said, “Do they have marijuana here?” And she said “No, they don’t.” And all of a sudden some other guy appears.

CH

(laughter)

PB

He was a dealer and I gave him fifty dollars. Next thing I knew he was dragging a fifty-pound burlap sack up the road. The smoke was outrageous. There’s just tons of it there.

CH

In Johannesburg, as a creative, what was your day like? You said you only made one painting. You were making large-scale sculptures. Who was your team? Who were you working with? Were you working at the Art Foundation?

PB

I was working at Rustenburg with Anthusa Sotiriades, who was one of the artists participating in the Thupelo Workshop. She was my student, friend, confidante, policewoman, survivor, human being. She was everything. I would have been gone without her. I mean, nonsense aside, South Africa was pretty scary in the ’80s.

CH

I remember, even when I was going to Johannesburg for the first time, you were like, “No, no, no. I ain’t going back there,” because you were still shaken up by the whole experience. Now you seem a little relieved from that tension. And you seem open to returning to South Africa.

PB

I don’t know if I can sit in an airplane for that long.

CH

I always thought we would get you on a boat, you and my father. Set up a studio on a big boat for those long trips. If we get you the right set up, we could get you there.

PB

I wouldn’t go unless you were there.

CH

So I want to know more about the Gallery Hirondelle at 476 Broome Street and what you remember from those days. Do you want to tell me about some of the shows you did with my father?

PB

John, you go first ‘cause your memory is better than mine. You owned the gallery.

John Hersey

We never thought Peter was making any art after we scheduled a show with him. He would be around, but he wasn’t in his studio. A few days before the opening, he worked about 48 hours straight putting a show together. Right? Peter was always so relaxed about everything.

PB

I remember that.

JH

No problems. And we’re all back there, “What the fuck is going on?”

PB

That’s right.

JH

And Peter pulled it off. Peter was the most looked-at artist in the gallery. We showed other artists, but people would turn their heel at the door and leave. There always were people in the gallery when Peter’s work was up. And they’d linger around for a long time, talking about each painting. It was a great time for the gallery.

PB

Yeah a great time for me. To get that type of exposure was tremendous.

CH

Is there a show in particular that you remember that stands out?

PB

Oh God! I can’t remember. There was a problem with a sculpture show we did once. There were too many sculptures in the space—too dense. I was thrilled I could make so many things, but I remember that show being cluttered. That’s probably not the answer you were looking for.

CH

I remember those pieces in person as a young child. But what other pieces did you show there? I’ve seen a lot of your paintings over the years. Do you remember any of the painting shows you did at the gallery?

PB

Yeah, we did a one-man show of paintings.

JH

I think we did two solo exhibitions of paintings and sculptures.

CH

Where were you making those sculptures and paintings for those shows?

PB

At the firehouse.

CH

Was that the primary space?

PB

Yeah, at the time. It was before I lost it.

CH

Where was it?

PB

On Lafayette and White Street.

JH

Just above City Hall.

PB

Engine House 33.

CH

And who were you working with, Peter? Were you doing all the work and the welding yourself?

PB

This guy named Lawrence Voker did a lot of the welding. He had trouble lifting heavy stuff, but he was ambitious. And we got it up.

CH

That must have been fun. And your paintings, did you have any help stretching them? It sounds like you were a one-man show.

PB

Yeah, I did all the stretching myself.

CH

That was a different time. And to see art explode in the market the way it did. To see Calders being sold for tens of millions of dollars, I mean what does that look like to you, having been around all those art works in the ’70s?

PB

As more time goes on the value goes up if you hold on to them, because they’re established in the market as an innovation, a work of art. It’s American. But America boomed a while ago. But only now is it starting to hit some of the names like David Hammons—of course he’s been doing some big numbers for a while.