April 1, 2019

Download as PDF

View on Artforum

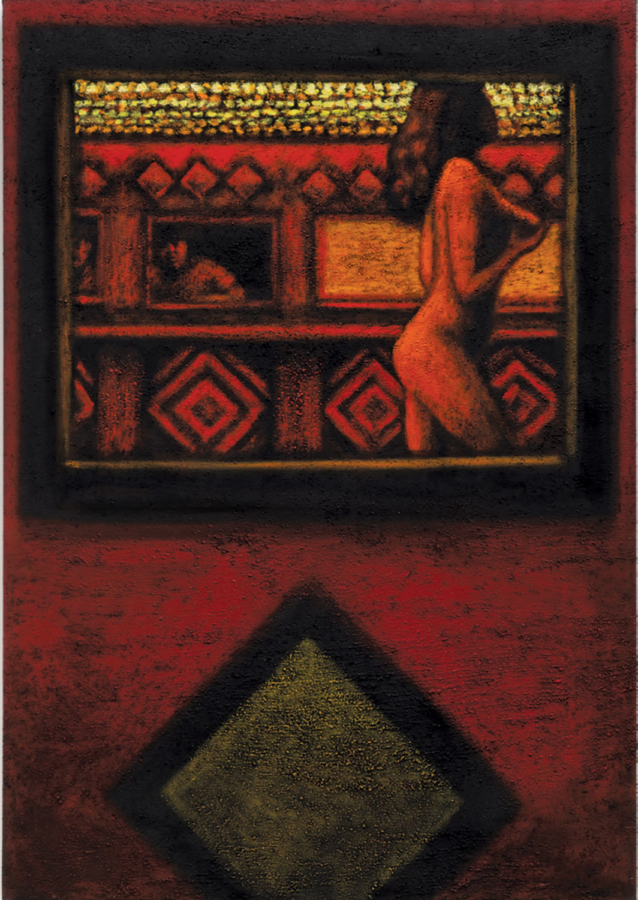

Jane Dickson, Peep VII, 1992–96, oil and pumice on canvas, 57 × 40”.

In 1978, the Chicago-born painter Jane Dickson was a few years out of college and looking for a job in New York. She answered a newspaper ad for artists “willing to learn computers,” and soon found herself on the night shift, designing animations for the first digital light board in Manhattan’s Times Square. Although she disdained what she called the “commercial propaganda” being broadcast on the Spectacolor screen, Dickson did manage to make the display work in her favor. First, she talked her boss into letting her commandeer it briefly to advertise the “Times Square Show,” the legendary 1980 exhibition held in a former massage parlor on West Forty-First Street and organized by the artist collective Collaborative Projects Inc., or Colab, of which she was a part. Later, she made the screen available to friends, including David Hammons, Keith Haring, and Jenny Holzer, all of whom used it to stage subversive interventions at the skeevy crossroads of the world. Dickson was closely connected to the city’s downtown scene, but as time went on, both her artistic practice and her personal life began to coalesce around these louche Midtown precincts. (She and her husband, Charlie Ahearn, a filmmaker and fellow Colab member, moved into a Times Square loft in the early 1980s, where they would live and raise their children for more than a decade.)

Attuned to the furtive actions in the shadows of the sex-shop neon, Dickson began photographing the scenes she came across and later started to paint them. The ten works on view at James Fuentes, made over the past thirty-five years, confirmed the artist’s reputation as a keen-eyed flaneuse with a uniquely impressionistic documentary style, reinforcing her project’s status as a vital chronicle of a mostly vanished New York demimonde. Some of the earliest paintings Dickson made in the city were done on black-plastic garbage bags, which allowed her to suggest the world of forms and figures emerging from darkness that she saw on her nighttime excursions, and throughout her career she experimented with other substrates such as carpet, sandpaper, and Astroturf. While the mostly large-scale works here were made with oil paint and oil stick on more conventional canvas and linen, they retain a vivid sort of graininess that suits her gritty subject matter. The textural effects of Peep VII, 1992–96, showing a nude dancer and a pair of leering men as viewed through the rectangular portal of a sex-show booth, or Witness II, 1991–97, in which a mostly hidden figure peers anxiously through the slats of a window blind, are aided and abetted, respectively, by pumice and Roll-A-Tex, a paint additive that provides texture. But more often the effect is simply a product of Dickson’s painterly approach, one that diffuses the surfaces and contours of people and buildings, bathing her nocturnal scenes in a dreamy astigmatic haze.

The kind of voyeuristic frisson exemplified by the peep show and the fretful watcher imbues much of Dickson’s work. In some instances, the gaze falls on the explicitly lascivious—as in Big Peepland, 2016, a large rendering of the infamous Forty-Second Street porn shop’s iconic high-concept doorway, with its carnal riff on the Eye of Providence—while others, such as Cops in Headlights, 1991 (based on footage from a home movie–style short called Doin’ Time in Times Square that Ahearn shot surreptitiously from the window of the couple’s loft in the early ’80s), evoke the frantic cadences of civic disorder. Yet in works such as Bus Stop s, 1984, in which a kid in a red balaclava is framed by a brightly lit tropical vacation ad, or Mother and Child, 1985, a familiar scene of a woman lugging her stroller-bound toddler up the subway steps as buildings loom darkly overhead, the sense of the urban environment as an inexhaustible source of tabloid fodder gives way to a more common, and arguably more affecting, ambivalence—a mix of lurking menace and utter normalcy that colors the rhythms of New York City life in any era.