November 6, 2021

Download as PDF

View on The Wall Street Journal

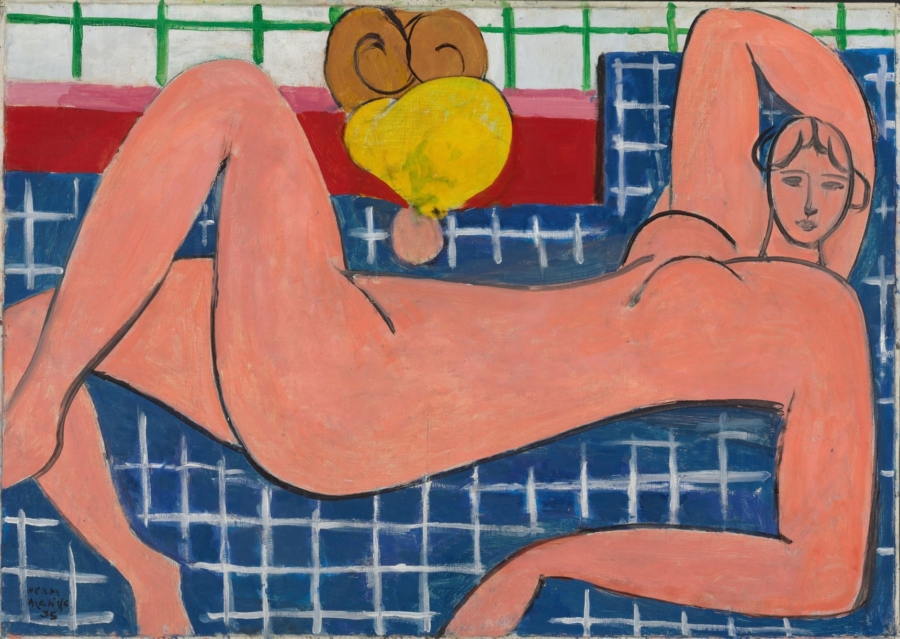

Henri Matisse’s ‘Large Reclining Nude’ (1935) PHOTO: SUCCESSION H. MATISSE/ARS, N.Y./ BMA

The Cone Collection at the Baltimore Museum of Art has long been a required destination for anyone wanting to understand, or simply enjoy, the art of Henri Matisse (1869-1954). Formed by two Baltimore sisters, Dr. Claribel Cone (1864-1929) and Etta Cone (1870-1949), it comprises some 600 works in all media by the artist as well as some of his illustrated books.

The Cone sisters first came into contact with modern art in Paris in the early years of the 20th century through their friendship with the writer Gertrude Stein and her family, who were some of the earliest collectors of Matisse and Picasso. The received wisdom has been that Claribel was the more adventurous of the two. Yet Etta lived for 20 years after her sister’s death, during which time she continued to acquire Matisses, enlarging the collection and working closely with the artist in deciding what to purchase.

“A Modern Influence: Henri Matisse, Etta Cone, and Baltimore” invites us to reconsider the standard view, bringing Etta out of her sister’s shadow to explore her role in making the Cone Collection what it is today. Jointly organized by Katy Rothkopf, senior curator of European painting and sculpture at the museum, and Leslie Cozzi, associate curator of prints, drawings and photographs, it consists of 167 paintings and sculptures; the preliminary studies for Matisse’s first illustrated book, “Poems” by Stéphane Mallarmé ; and abundant works on paper, among them portrait drawings of Etta and a Matisse self-portrait. Some works have rarely been seen, while others are on view for the first time. Though marred by one large missed opportunity, it is an important, even revelatory, exhibition that shines a bright light not just on Etta but on the way Matisse thought and worked. And it inaugurates the new Ruth R. Marder Center for Matisse Studies at the museum, which Ms. Rothkopf heads.

The exhibition opens with Etta’s earliest purchases, made in 1906. The most striking is “Yellow Pottery From Provence” (1905), a painted still-life whose eponymous jug is not just yellow but green, purple, ochre and red, and casts brown shadows. The work is loosely brushed in and there are patches of unpainted canvas, leaving one to wonder if Matisse abandoned it or considered it in some sense finished.

In works like this Matisse was forging a new direction in painting, where color wasn’t used descriptively but expressed the painter’s emotional response to the subject before him. It was a turn that famously elicited strongly negative reactions from most of those who saw Matisse’s work at the time. Therefore, for Etta Cone—newly exposed to the avant-garde and with no deep background in art—to have bought “Yellow Pottery” was bold and visionary.

As we move through the show we learn that it was Etta who was responsible for acquiring works that are not just masterpieces of the collection but of Matisse’s art generally: “The Yellow Dress” (1929-31) in which he upends convention by making the sitter’s attire, not her physiognomy or character, the focus of his attention; and “Interior, Flowers and Parakeets” (1924), considered a keystone work of that decade.

One of the highlights of “A Modern Influence” is a show-within-a-show. “The Yellow Dress” is displayed surrounded by over a dozen preparatory drawings recently donated by the Matisse family and another benefactor. In the painting the model is shown seated in hieratic frontality before an open window. The drawings show Matisse beginning by studying the isolated figure in a variety of poses and attitudes, then situating her in an interior before finalizing the pose, after which he was ready to begin the hard work of painting.

But while “A Modern Influence” tells us a great deal about what Etta bought, it tells us almost nothing about why she did so—in other words, about her taste. Almost the only insight we are offered is that, as one wall text reports, “Cone appreciated Matisse’s celebration of the female body and all of its postures. This subject may have resonated with her own intimate same-sex relationships.” (Etta never married and had a longtime female companion.)

This reading strikes me as owing more to the zeitgeist than to a close study of Etta’s actions and artworks. The reality is subtler and more interesting. For all the breadth and representativeness of Etta’s acquisitions, there is none of the Cubism-inspired work of the years 1913 to 1917, in which Matisse’s art came as close as it ever would to pure abstraction. The absence of such work suggests that while Etta was willing to follow almost wherever Matisse led, her taste was circumscribed by the need to remain tethered, however tentatively, to what she knew, the world of visual appearances. This is no judgment against her—she was hardly the only modern art collector of the time who felt Cubism asked of them more than they could give.

There are exceptions to this rule, notably “Large Reclining Nude” (1935) with its radically simplified figure and pancake-flat pictorial space. More’s the pity, then, that “A Modern Influence” does not take the opportunity to explore the relationship between audacity and conservatism in Etta’s collecting. Perhaps the new study center can put it on the agenda.

***

Prior to the 20th century, sculpture was made by modeling or carving. Then Picasso invented assemblage, the practice of attaching disparate elements together. Thaddeus Mosley does both: He carves and shapes pieces of felled timber and then assembles them into abstract sculptures. The magical results of this effort can be seen in “Thaddeus Mosley: Forest,” a show of just five works. It was organized by Jessica Bell Brown, the museum’s associate curator of contemporary art, who has displayed them

Mr. Mosley (b. 1926) is largely self-taught, and this redounds to his benefit—he never became hostage to any particular aesthetic dogma. Thus his sculptures, vertical and mostly human-scaled, blend the innocence of folk art, the forms and textures of African art and the formal language of modernism. They are equally wide-ranging in what they evoke: bodies in motion as well as physical forces such as weight and balance. This is a buoyant, deeply engaging display by an artist who deserves to be far better known.