December 15, 2021

Download as PDF

View on Art in America

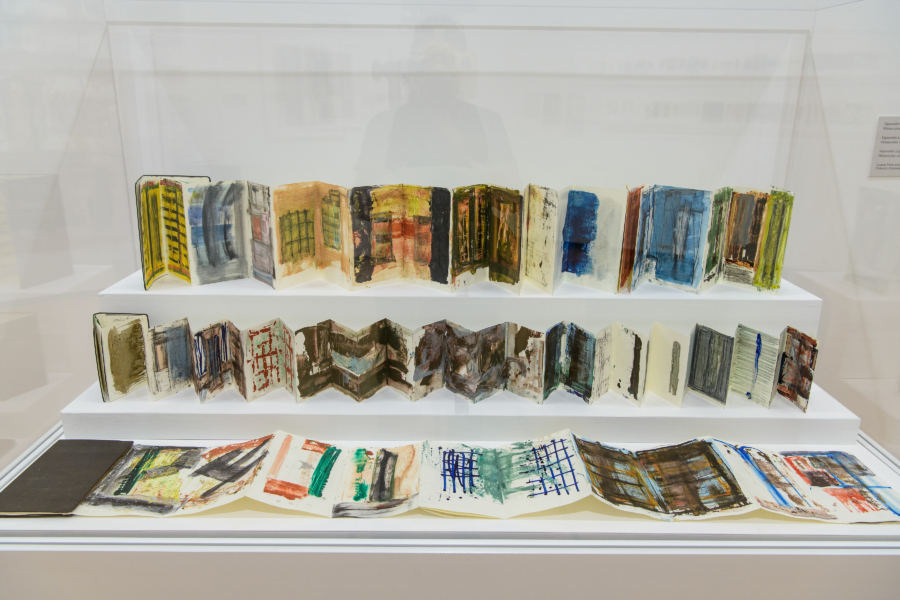

View of “A Question of Emphasis: Louise Fishman,” 2021–22, at Krannert Art Museum. PHOTO DELLA PERRONE/UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS KRANNERT ART MUSEUM

“Abstract painting is not easy to write about,” the late artist Louise Fishman once said, expressing both a general truth and a personal concern. Perhaps finding that paper—a medium for verbal as well as visual articulation—was most useful for helping her negotiate this dilemma, Fishman annotated many of her works on paper with all-caps script, an ever-expanding set of diaristic fragments and ideas that thread throughout this sensitive and immersive survey of her drawings. “This is working class Jewish lesbian art. In case you didn’t already know,” one pencil sketch from 1973 puckishly asserts. The image portrays an idiosyncratic pie chart in which a circle is partitioned into variously shaded segments accompanied by notational self-talk. Fishman’s inner dialogue is alternately chastising (“not tough enough”) and vulnerable (“What I often forget is that headaches are being scared—these 3 drawings are being scared”), making the otherwise modest piece feel like a significant summary of her perpetually interrogative practice, which has heretofore been defined by her large-scale paintings.

Spanning the course of Fishman’s career, from her years in the MFA program at the University of Illinois in the early 1960s through 2018, the more than one hundred works on display at the Krannert Art Museum are taken almost entirely from Fishman’s personal collection and most have never before been exhibited. Eschewing a linear, developmental structure, the show—which was organized by the museum’s curator of modern and contemporary art, Amy L. Powell, in close collaboration with the artist, who passed away just a month before its opening—is instead arranged according to Fishman’s formal grammar, with sections titled “Transfers,” “Grids,” “Curves,” “Flat Folds,” and “Expressions.” Within each, graphic and painterly gestures, chronologies, and materials collapse and intermingle. In “Grids,” for instance, a thick and blocky oil-on-paper drawing from 1975 appears near a loosely scrawled oil-and-oil-stick painting from 2001; in “Curves,” a grid of broad crosshatches from 2001 hangs adjacent to a series of sketchy ink-on-paper silhouettes of horses from 1995. Walking back and forth through the galleries, one becomes attentive to Fishman’s creative strategies but also detached from their specificity—seeing, instead, how they fueled an ongoing process of invention and revision, disclosure and occlusion.

The show’s most consistent form is the accordion-style leporello book, nearly a dozen of which are dispersed throughout the exhibition, their interiors unfolded to reveal intricate paintings that either embrace the rhythm of sequential images or traverse the pages to create a continuous whole. Fishman turned to the leporello in 1992, after a fire destroyed her studio, along with all of her art and belongings within it. It was a paralyzing trauma from which she slowly rebuilt herself by filling up the small pages of these little books, whose origins can be traced to Don Giovanni’s long scroll of romantic conquests, as well as a Buddhist tradition in which pilgrims chronicle their visits to sites on the Buddha’s journey to enlightenment. Channeling both lineages, Fishman’s books are often specifically addressed to past or current lovers and serve as meditative registers for her varied formal approaches. They also act as collapsible works that combine literary and artistic associations, asking to be both read and viewed. Book of Abuse (1993–94), a particularly powerful example, is dedicated to her former lover Bertha Harris. Its pages move from ripped, gouged, and crudely layered black-and-white painted collages to darkly hued color fields with a bright central gash; midway through the book, the gash slowly becomes the compositional focal point, and shifts from a watery maroon mark to a crisp column that ultimately bursts into a colorfully effulgent grid. Such transformations give the sense of a narrative arc, from tangled tumult to an erotic climax that resolves in ecstatic clarity. While less explicit, this narrative impulse, once identified, can be seen throughout the show, whether in Fishman’s intermittent self-reflections, the trajectory of her gestural experiments, or her more serial imagery. Another book, from 2013, is inscribed: For the dear one, my love, Ingrid on your birthday April 9, 2013 your loving and doting and still trembling spouse, Louise—a love story writ in sensually saturated drips, stains, and pools of green, yellow, and blue paint interspersed with clippings of Ingrid’s hair.

In a 2016 interview, Fishman explained: “It has always been a problem for my career that I am one, queer, two, a woman, and three, doing plain old abstract paintings. There’s not the subject matter that you see in other lesbian work—subject matter that makes things more accessible and easy to write about.” That tension—between legibility and illegibility, abstraction and representation—is at the center of this exhibition. And the leporello books—private artifacts, here made public, that can be expanded into near-epic compendiums of a lifetime’s worth of emotive marks or collapsed into pocket-size archives of affection and artistry—feel like its intimate guide.