May 1, 2022

Download as PDF

View on The Brooklyn Rail

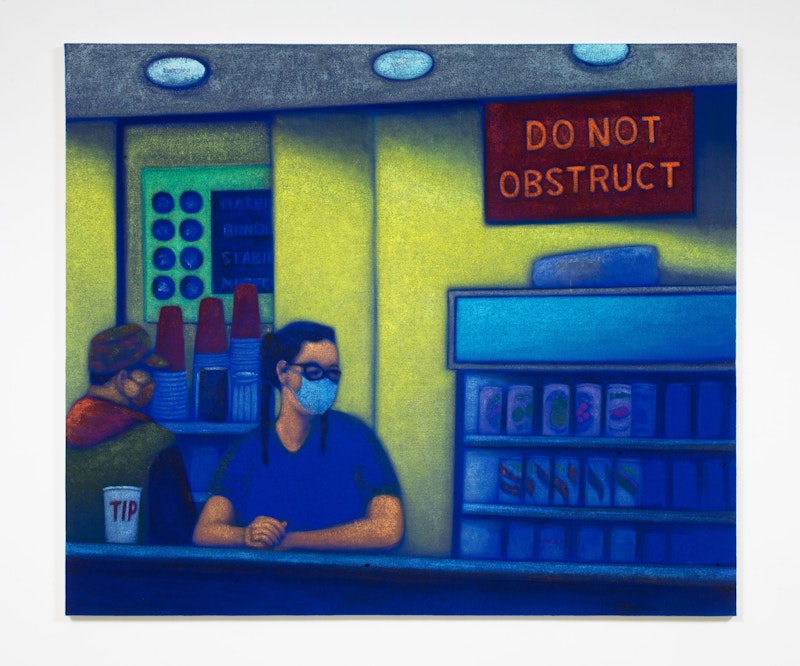

Jane Dickson, Do Not Obstruct, 2021. Acrylic on felt mounted on canvas, 63 × 74 inches. Courtesy the artist and James Fuentes. Photo: Jason Mandella.

An overwhelming desire for the past looms in the air; indeed, one reminder of this sentiment—and it’s a stunning one—is 99¢ Dreams, Jane Dickson’s current exhibition of new paintings at James Fuentes Gallery. The seventeen paintings on view were made in the last two years during lockdown; most are oil stick on linen or felt and three are acrylic. Neo-Impressionist layers of paint smudges resembling film grain call to mind the photographs referenced here, as these paintings are based off of shots the artist took after dark in the 1980s of theater marquis, flashing neon signs, dark alleys and bright storefronts that describe her personal history in Times Square. Dickson translates the still scenes into colorful and juicy paintings that seem to pull away from the gallery walls and at the same time sink into them.

In Do Not Obstruct (2021), a telephoto perspective reveals two figures working the late shift at a diner. The painting has a tone reminiscent of a modernized version of Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks (1942). The scene could be set in the 1980s, but COVID-era face masks worn by the stars of the encounter hint not. One subject stands with their back toward us, sporting a hoodie, vest, and cap, while the other faces outward, resting their arms on a countertop, hands clasped, shoulder cocked, gazing left. A cup with the word “TIP” rests beside them on the counter, and a sign in the right of the frame reads “DO NOT OBSTRUCT.” A blue felt background heightens color saturation and depth of the dominant red, blue, and yellow.

Liquors Sallys Hideaway (2021) depicts a cinematic wide-screen view looking out a window, presumably the artist’s. Shadows creep in from the edges of the frame, allowing the shop’s light to illuminate the actions of people on the sidewalk, depicting each in different states of their day. A New York Times delivery truck is on route to deliver the paper, a cab driver and friends are hanging out, two people listen to music on a boombox while watching one dance. The liquor store sign blasts a cerise glow into the gallery space. The body style of the automobiles reveal this moment happened over 30 years ago.

99c Dreams 3 (2022) depicts a detail shot of a storefront and signage with Rothkoesque blue and green color fields leaping off the gallery wall. Accented yellow squares in the lower half of the canvas resemble overhead lighting and bold orange-red sans serif type in the key of Ed Ruscha read in all caps “99C DREAMS EVERYTHING $1 & UP, 99C DREAMS.”

In conjunction with the exhibition, James Fuentes Press has published a book on the artist and her work, featuring an interview with Odili Donald Odita, in which Dickson explains, “At this point in my life, my trajectory is not linear anymore, it’s a spiral. Over the last two years, I had time to reconsider my history. I’m a different person and the world is a different place and this neighborhood, as it stood, no longer exists.” Reflecting on these words, one thing that comes to mind is the phenomena of earthly perspective of light emitted from a star that died long ago but remains visible. Observation of that light has nothing to do with the absence of the star itself, neither does appreciation of a disappeared New York made visible through these paintings; that energy still reverberates through the stroke of the artist. Desires are unchained to temporal shifts and the most lucid dreams still come at night. “My show is called 99¢ Dreams, and I’m noticing that keyboards don’t have a cent sign anymore. I’m trying to type it, but the cent symbol is gone. I guess you can’t have dreams that cheap anymore.” On the contrary, one takeaway from the last two years is that dreaming is the cheapest way to travel.