June 6, 2022

Download as PDF

View on Fresh Water

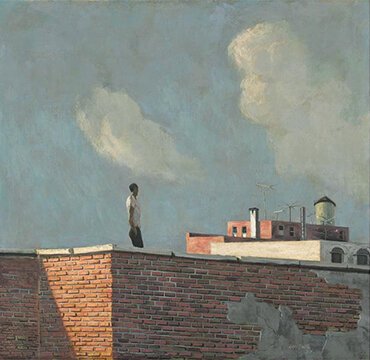

Rooftop, by Hughie Lee-Smith; Cleveland Museum of Art

The most highly acclaimed Black artist to have come out of Cleveland is, by general consensus, Hughie Lee-Smith (1915–1999). The Cleveland Museum of Art website describes him as “one of the most gifted figural painters of his generation.” One of Lee-Smith’s most famous paintings, “Rooftop,” is waiting there for you to consider and contemplate, and maybe discuss with a friend.

If you’re interested in learning more about this strangely compelling work, and what led to it, the museum will host a free talk by the Cleveland Institute of Art (CIA) associate professor of art history David C. Hart tomorrow, Tuesday, June 7 at 12 p.m.

In fact, Lee-Smith learned his craft at CIA, and Hart says he thinks Lee-Smith’s paintings have a lot to say to us about life in America.

Especially the experience of Black men in America.

It has been said that Lee-Smith “found art lurking in loneliness.” It’s no accident, says Hart, that so many of his paintings depict isolated, solitary figures in desolate urban settings or remote landscapes with foreboding skies, often positioned with their backs to us. Sometimes with the subjects’ backs to one another.

It’s as if the whole scene is saying something important to the painter. As many commentators have remarked, the human subjects are almost invariably pictured in what the Canton Museum of Art calls “real world” settings, with “boarded tenements, crumbling brick, crackled facades, and empty streets.”

Lee-Smith’s paintings have been called a blend of the “cool urban realism” of Edward Hopper and the “metaphysical surrealism” of Giorgio de Chirico.

For Hart, it’s all about the loneliness and introspection Lee-Smith attributed to his experience as a man of color in mid-20th Century America. He came to see his attraction to certain subjects and situations and the way he rendered them, though he says it was largely unconscious, as having “a lot to do with alienation.

“In my case, aloneness, I think, has stemmed from the fact that I’m Black,” Lee-Smith concludes, according to the Smithsonian website. “Unconsciously it was a lot to do with a sense of orientation.”

On another level, Lee-Smith’s work speaks powerfully to the inability of many of us to reach out to, and connect meaningfully with, our fellow human beings—especially people of other races.

Growing up in Cleveland in the 1920s, Lee-Smith attended East Technical High, where he ran track with Jessie Owens. A young Lee-Smith soon found himself spending a lot of time at Karamu House, learning the art of printmaking under Langston Hughes while taking classes at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

With the help of artist Charles Louis Sallée, Hughes secured Lee-Smith a scholarship to CIA, (where he hyphenated his last name to stand out from the sea of Smiths) and graduated with honors in 1938.

But Lee-Smith was soon forced to take a job in Detroit in one of Henry Ford’s factories. It was in the Navy—where he undoubtably endured many indignities at the hands of the white sailors and officers—his talent finally paid off.

As one of three Black sailors commissioned to do morale-building paintings, he produced a mural, “The History of the Negro in the U.S. Navy,” which depicted portraits of several Black naval officers, before he returned to Detroit and doggedly pursued a bachelor’s degree in art education from Wayne State University so he would have a way of making a living as an artist.

In 1953, the same year he earned his degree, Lee-Smith was awarded Detroit Institute of Arts’ Top Prize for Painting.

Years later, he recalled his feelings on receiving that signal honor: “I was no longer called Black artist, Negro artist, colored boy. When I won that prize, all of a sudden, there was no longer a racial designation.”

Today Lee-Smith’s paintings are found in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the San Diego Museum of Art, Howard University and New York Public Library Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. He was the second Black person to be elected to the National Academy of Design.

This year Lee-Smith is being celebrated in his own home town as one of Cleveland’s Past Masters, a joint initiative of Cleveland Arts Prize and the Western Reserve Historical Society. He is being honored not merely as a trailblazing Black artist of distinction, but simply as a wonderful painter whose lifetime of work still has a great deal to say to us.