September 1, 2022

Download as PDF

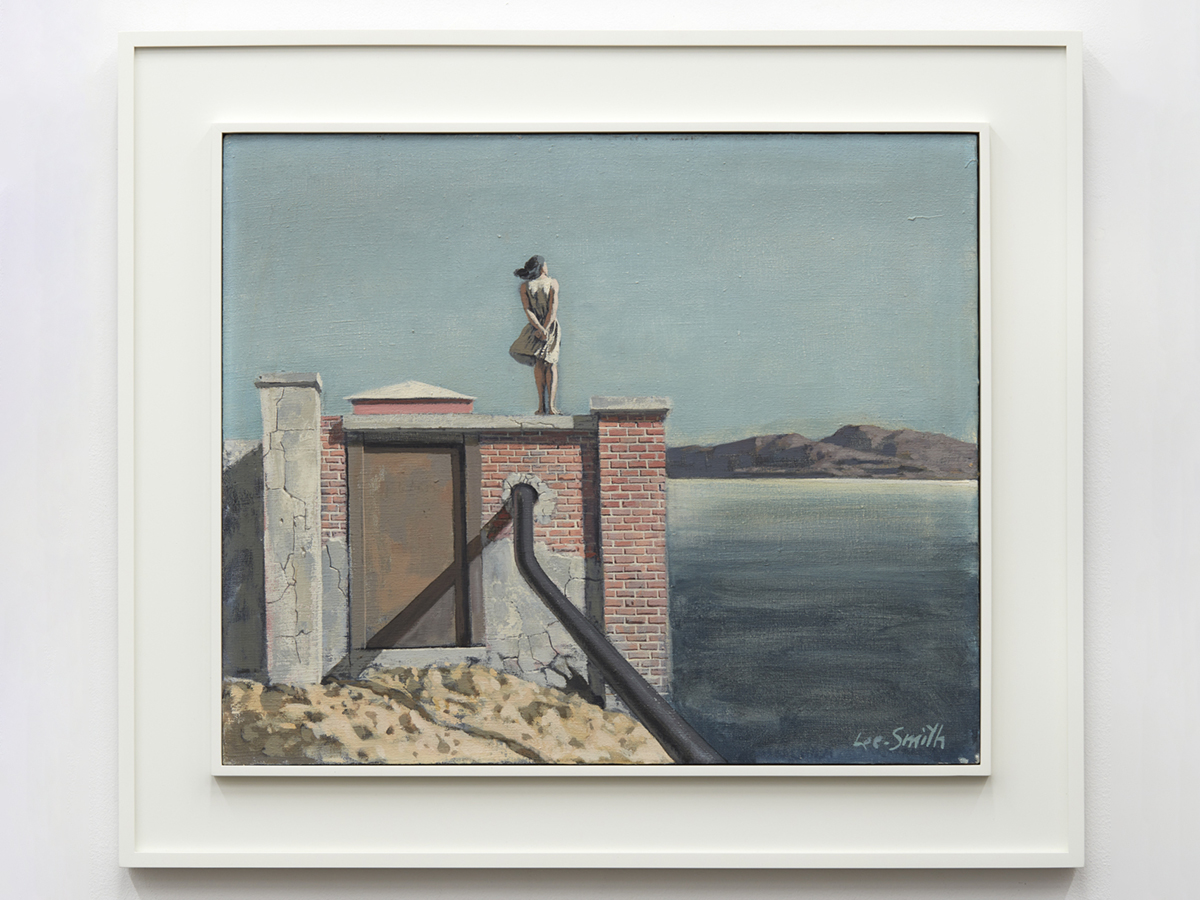

View on The New York Times

The small paintings of Hughie Lee-Smith (1915-1999) are frequently said to combine two prewar styles — American Scene realism and European Surrealism — into distinctly postwar depictions of crumbling townscapes and waterfronts. Beautiful in their play of light and shadow, and their exquisite color contrasts, these tableaus have the dreamlike stillness and artificiality of deserted stage sets. They never have more than two or three occupants; most are Black, some are white, all are isolated and alone.

Maybe Lee-Smith’s structures are being repaired, not demolished, but their patchwork disarray makes delicately yet unavoidably manifest the inherent, tragic rottenness of American society. His lithe, dreamy figures indicate this rottenness as predominantly racial and inescapable: Everyone is affected, regardless of skin color. All dreams will remain unfulfilled.

Less, however, has been made of Lee-Smith’s deft paint-handling and the ways he vacillates from the trompe l’oeil minutiae of cracked bricks and peeled paint, to the almost abstract brushwork of horizons, construction sites and buttes of dirt or landfill. At times he seems like a miniaturist Manet, loving paint for its plasticity and color, but also for its ability to create a spellbinding balance of surface and space where poetic, political and philosophical meanings are equally palpable.

With 34 paintings from 1949 to 1997, this is the largest survey of Lee-Smith’s work held in New York in more than 20 years. His art has only gained poignancy and pertinence.