April 2, 2022

Download as PDF

View on Hyperallergic

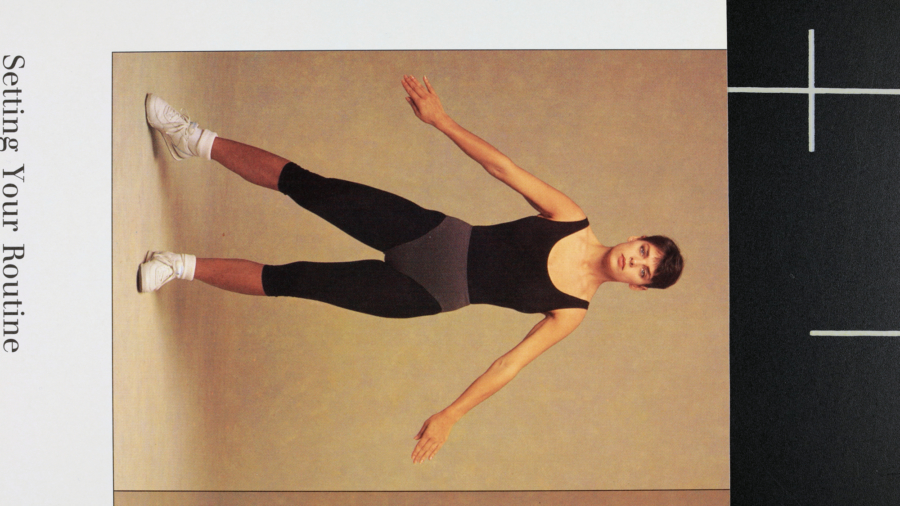

Still from Mungo Thomson, “Volume 2. Animal Locomotion” (2015-22), 4K video with sound, 5:21 minutes. Music: Laurie Spiegel, “Clockworks” (1974) (all images © Mungo Thomson, courtesy the artist and Karma, New York)

Thomson’s videos conjure up the weird sublimity of internet wormholes, the familiar, swaddling mindlessness of allowing oneself to be swept up in a deluge of content and carried — where?

First: a single copyright sign. Then, the camera incrementally retracts to reveal surrounding text — names, dates, rights holders — shifting at stop-motion’s brisk frame rate. Set to a soundtrack that overlays mechanical whirring with chiming and clanging, Mungo Thomson’s 12-minute video “Volume 1. Foods of the World” (2014-22) proceeds to flicker through seemingly infinite pages of recipes, an unremitting staccato of culinary instructions and demonstrative images: a marbled plate of neat canapés or tiered cake smothered with buttercream, hands whisking or slicing or kneading, and even — in a seriously granular approach to the language of cooking — a classificatory torrent of apple varieties.

One of seven short video “volumes” on view, movie-theater style, in Thomson’s solo show Time Life at Karma, the work culls its content and title from a cookbook series published by Time-Life from 1968 to 1971. Time-Life, a purveyor of popular mail-order encyclopedias, mined the photographic repositories of general interest magazines Time and Life to produce image-dense volumes on topics ranging from wildlife to seafaring to computers. Time-Life books, which the Los Angeles artist recently characterized as a “proto-internet,” were a staple of middle-class households across the United States in the 1970s and 1980s; in 2001, as the United States ushered in a new millennium via dial-up, Time-Life publishing folded. Thomson, for whom mass media — and mass-mediated experience — are artistic touchstones, has explored Time in the past: previously, he traced the magazine’s evolving font, and produced mirrored versions of its covers emptied of content.

Like a Soviet Kino-Eye with a wink, the videos in Time Life assign the viewer the perspective of a robotic scanner busily cannibalizing books to transform them into digital data. Laid atop a gridded base, the pages are sporadically sideways, nonsensically cropped, or atomized through proximity; at one fantastically animated moment, they even whirl around the book’s spiral binding as if it were a maypole. The image-saturated spectator, whose fixed eye is not permitted rest, operates at the machine’s pace: high-speed scanners can process eight pages per second, about the same frame rate employed by Thomson’s stop-motions. In their imbrication of contemporary and pre-digital technologies (scanner and stop-motion, e-book and print book, internet and encyclopedia), these works ask what is lost, produced, and altered through sweeping digitization. Is analogue existence transformed, on an ontological level, in the process? Are we?

In the spirit of Time-Life books, each of Thomson’s video volumes brings an encyclopedic scope to a single theme, such as flowers, search-engine-style questions, and knot-tying (the latter a metaphor, perhaps, for the Gordian knot of Thomson’s inquiry). “Volume 2. Animal Locomotion” (2015-22), aptly titled after Eadweard Muybridge’s proto-stop-motion experiments with motion photography, plucks images from fitness how-to books to depict individuals moving flip-book-style through lunges and squats, dance moves, and yoga poses — including yoga performed at desks. In a similar vein as Foods of the World’s copyright sign, which wordlessly evokes the intellectual property issues accompanying digitization, the predominant Whiteness of the bodies throughout “Animal Locomotion” implicitly gestures toward the data biases that feed algorithmic racism.

Not all of Thomson’s volumes are rooted in Time-Life. “Volume 5. Sideways Thought” (2020-22) features photographs of sculptures by Auguste Rodin depicted from so many angles that they appear three-dimensional, a feat that clearly necessitated photographic sources beyond Time-Life’s The World of Rodin book — perhaps drawing upon the thousands of photos personally overseen by Rodin, an early adopter of photography and subscriber to Muybridge’s “Animal Locomotion” (which Muybridge made available on a subscription basis). The final video in the sequence, “Volume 7. Color Guide” (2021-22), takes a macro lens to a printed Pantone color guide; in a play on the work of California Light and Space artists like James Turrell, flashing fields of pure, grainy color overtake the screen and flood the dark theater. The empty, trance-like state provoked by viewing the work conjures up the weird sublimity of internet wormholes, the familiar, swaddling mindlessness of allowing oneself to be swept up in a deluge of content and carried — where? By whom? And why? It’s something to think about.

Mungo Thomson: Time Life continues at Karma (22 East 2nd Street, East Village, Manhattan) through April 16. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.