Spring 2022

Download as PDF

View on Nuvo Magazine

Photographer Guillaume Simoneau

“We don’t have the biggest stories, legends, and characters, but we have this incredible landscape,” Lausanne-born, New York–based artist Nicolas Party says regarding the influence of his home country, Switzerland, on his practice. Though known for his figurative, colour-saturated portraits, sculptures, and murals, the concept of landscape, and its relation to national, geographical, and cultural identity, fascinates Party, and in certain ways his multicoloured murals and backdrops could be considered landscapes of sense and feeling. His forthcoming exhibition, L’heure mauve at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA), explores, he says, humanity’s current anxious relationship to nature. In light of this, Party connects landscape and cultural zeitgeist. “It wasn’t until the late 19th century that the British began popularizing mountain tourism in Switzerland,” he explains. “Before that, the countryside was something to travel through en route to European cities.”

Party has been on something of a global tour himself of late. During 2021, he had high-profile, solo exhibitions in Dijon, Hanover, New York, and Switzerland. He also created a large-scale mural, Draw the Curtain (2021), that wraps 360 degrees around the famed cylindrical exterior of the Hirshhorn Museum beside the National Mall in Washington, D.C. And a new monograph, Nicolas Party, came out in February 2022 as part of Phaidon’s Contemporary Artists Series. In addition to receiving critical acclaim, Party’s work has been surging on the commercial market.

When we speak via phone, the artist is in Montreal to install L’heure mauve (Mauve Twilight) at MMFA, bringing together watercolours, pastels, and sculptures that include about 20 recent works not previously exhibited. As part of the exhibition, Party has also curated 50 pieces from the museum’s permanent collection to be shown in seven thematically organized rooms alongside his own work. Given his frantic pace and mounting success, I half expect Party to sound exhausted, yet he’s alert and affable. He’d been in Montreal briefly before the holidays, he says, and then returned after New Year’s Eve to discover the city in lockdown with a 10 p.m. provincial curfew in place.

These days, Party works between New York City and a home he and his partner recently purchased upstate in the Catskills. “I always say that I moved [to New York] for love, though in the end it was also good for work,” he says. He was living in Brussels when he met his partner, a writer. “It made sense for her to be in a place that was English speaking,” he adds, noting that he didn’t mind returning to an English-speaking place after living in Scotland, where he completed his MFA at the Glasgow School of Art in 2009. I ask how living in New York has affected his trajectory. “It’s very active and dynamic,” he observes, continuing, “There are the big commercial painting galleries, but there’s also a lively museum culture. It sounds cliché, but being in New York has definitely made certain opportunities more possible, but it also promotes a very specific type of career. I still feel very, very lucky that certain things have worked out for me.”

When we return to discussing L’heure mauve, Party tells me the title was taken from a painting by the same name by Ozias Leduc, a self-taught Québécois symbolist. Party discovered Leduc’s L’heure mauve (1921) in the MMFA’s collection, and it’s one of the pieces he’ll be showing alongside his own works. Upon first look, Leduc’s painting of a branch that has fallen into snow is deceptively simple. Dry, delicate oak leaves and partly covered tree limbs peek through warm, sepia-tinged snow. There’s a sense of both permanence and change, with the dead leaves alluding to growth and the smooth snowdrifts emblemizing winter and, by extension, death—showing the symbolist trope of landscape revealing interior truths.

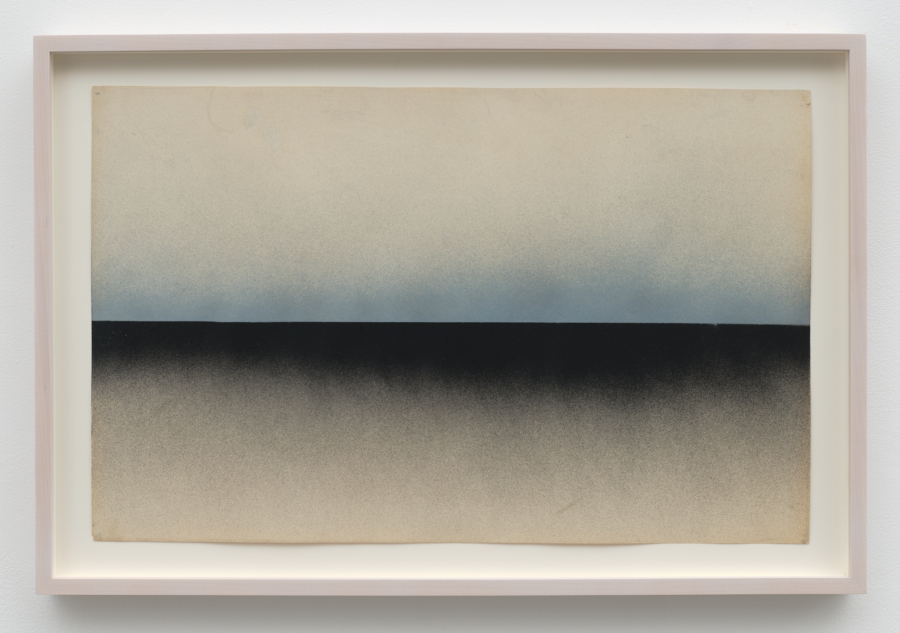

Party’s work deals in unresolved polarities. His portraits often feature figures who are ambiguous in terms of age and gender. These subjects embody a Modigliani-esque elegance and severity, and they typically appear on two-dimensional planes and in front of solid-colour backdrops. Many of the figures themselves are also brightly hued and posed with creatures or objects from nature rendered in an uncanny scale or position. Like his portraits, Party’s landscapes and sculptures evoke tension between familiarity and strangeness. A biomorphic quality threads across his work, wherein figures are questionably human, and landscapes and objects feel somehow alive. In Sunrise (2018), candy-floss-pink banks slope down to a body of icy blue water, with colourful trees with curved edges dotting the shore—the effect makes me think of Lawren Harris on psychedelics. In Still Life (2017), an assortment of purple, pink, orange, and blue fruit- and vegetable-like forms lie in a semianimate heap reminiscent of a Giorgio Morandi painting.

Party is classically trained and attended the Lausanne School of Art before completing his MFA. Before graduate school, however, he came of age as a graffiti artist in Lausanne. This heterogeneous educational background makes sense considering the control he wields over viewers’ attention. His work has an iconic quality—as assertive as 1960s pop art, but with less readily yielding, and therefore more seductive, subtexts. Beyond crafting unforgettable two- and three-dimensional images, Party is also known for altering gallery and museum architecture to facilitate more immersive encounters with his work. In Grotto, a 2019 exhibition at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels, Party painted the walls vivid colours and replaced doorways with Florentine archways. In an interview with Eric Troncy, Party explains that the arch creates a sort of leap in time, thereby summoning myriad cultural associations while also making the space more intimate for viewers.

It’s easy to be disarmed by Party’s creations. His work is often described as dreamy or dreamlike, so I inquire if dreaming feels important to him—either literally or as an imaginative tool. Party replies that dreams qua dreams are not especially important to his process, but he acknowledges a presiding interest in how ideas about dreaming are deployed within different cultural frameworks. He is intrigued by “the moment when dreams almost become a material within psychoanalysis,” also noting that “the uncanny idea of mixing two things that don’t go together has always existed.” Hybridity and the combination of opposites is part of ancient as well as future-looking cultures, so of course, Party admits, the broader implications of dreaming interest him, too. This meta-fascination with art’s historical interpretations of dreaming has no doubt informed some of the surrealist dimensions of his work. Curators have noticed, too. In 2018, Party showed alongside works by the 20th-century surrealist René Magritte at the Magritte Museum, an invitation Party still expresses gratitude for.

A standout of this oneiric influence was Party’s first solo show with Hauser & Wirth in Los Angeles in 2020. The exhibition was called Sottobosco in reference to the Dutch artist Otto Marseus van Schrieck’s still lifes, which featured objects from the forest floor seen in microscopic detail. In Party’s Portrait with Mushrooms (2019), a sea-green figure looks straight at the viewer. The sitter’s long nose, sculptural brows, catlike yellow eyes, and serious expression purport a serious mien, and yet there’s concomitant absurdity and lightness to the painting. Large yellow, orange, and brown mushrooms appear at various angles in front of the figure’s chest, with the complementary shapes of the figure’s body and the oversized fungi suggesting some spiritual, if not bodily, alignment between the figure and the fungi. Party tells me that all the mushrooms in the painting “were based on ones I saw in sottobosco paintings by Otto Marseus van Schrieck.”

Lucid attention to detail evidently fuels Party, who is anticipating another busy year in 2022. He strives to make work that is aware of its context, and looping back to our conversation about landscape and his show in Montreal, Party explains that he’s been thinking a lot lately about our extreme anxiety toward the environment and climate change. “When I think of my childhood and my home country Switzerland, landscape is a recurring theme,” Party reflects. He presents layered concepts via smoothly assertive imagery. The emotional and dreamlike vistas he reveals give insight into not a romanticized idea of landscapes but of the way that art recreates them. For him, it seems knowing something for certain is less important or pleasurable than discovering the next mysterious question—almost like following a dream.