June 1, 2022

Download as PDF

View on Artforum

I remember seeing the films of Mungo Thomson in 2009 at John Connelly Presents, one of the NADA galleries that occupied a row of storefronts on the western end of Twenty-Seventh Street in Manhattan’s Chelsea district. Derek Eller Gallery, Foxy Production, JCP, Oliver Kamm/5BE Gallery, and Wallspace all used to coordinate their openings for the same evening, encouraging a block-party atmosphere that reliably spilled out onto the street—so much so that the NYPD caught on and started rolling through to issue tickets for outdoor drinking. (Once, as two of my friends were being written up, I heard a senior critic wonder aloud whether police officers were consulting the calendar of openings posted on the Douglas Kelley Show List.) At JCP, Thomson screened two works shot on 16-mm film, both silent but for the clanking whir of their projectors. Each hearkened back to the 1960s and ’70s. The first took the blank leader from Nam June Paik’s Zen for Film, 1962–64—one of the pieces in George Maciunas’s Fluxfilm Anthology—and reversed its polarity. The dust-flecked white of Paik’s original became a glittering starscape. The second focused on the archived Rolodex that Los Angeles’s Margo Leavin Gallery had maintained since 1970. Through jerky stop-motion animation, the Rolodex came to life, flipping through the phone numbers and addresses for a fabled assortment of names: CASTELLI, JUDD, KOSUTH . . .

I guess I’m being doubly nostalgic here, reminiscing about a gallery scene where you could sip a can of PBR while contemplating the 1960s. Though usually considered an inheritor of the cheerful LA Conceptualism promulgated by John Baldessari, Thomson (b. 1969) identifies as a child of Northern California, raised among the dissipating energies of the counterculture. A film such as Untitled (Margo Leavin Gallery, 1970–), 2009, recovers the past through both medium and message. The celluloid reel, Rolodex, and roster of art-world contacts are all perfectly synced to evoke the same period style. (Side note: Don Draper’s famous Mad Men soliloquy on slide carousels first aired in October 2007.) The consistent anachronism of Thomson’s earlier work stands in contrast with the temporal drift of his exhibition “Time Life,” a series of seven digital videos with references drawn freely from the nineteenth century to the present.

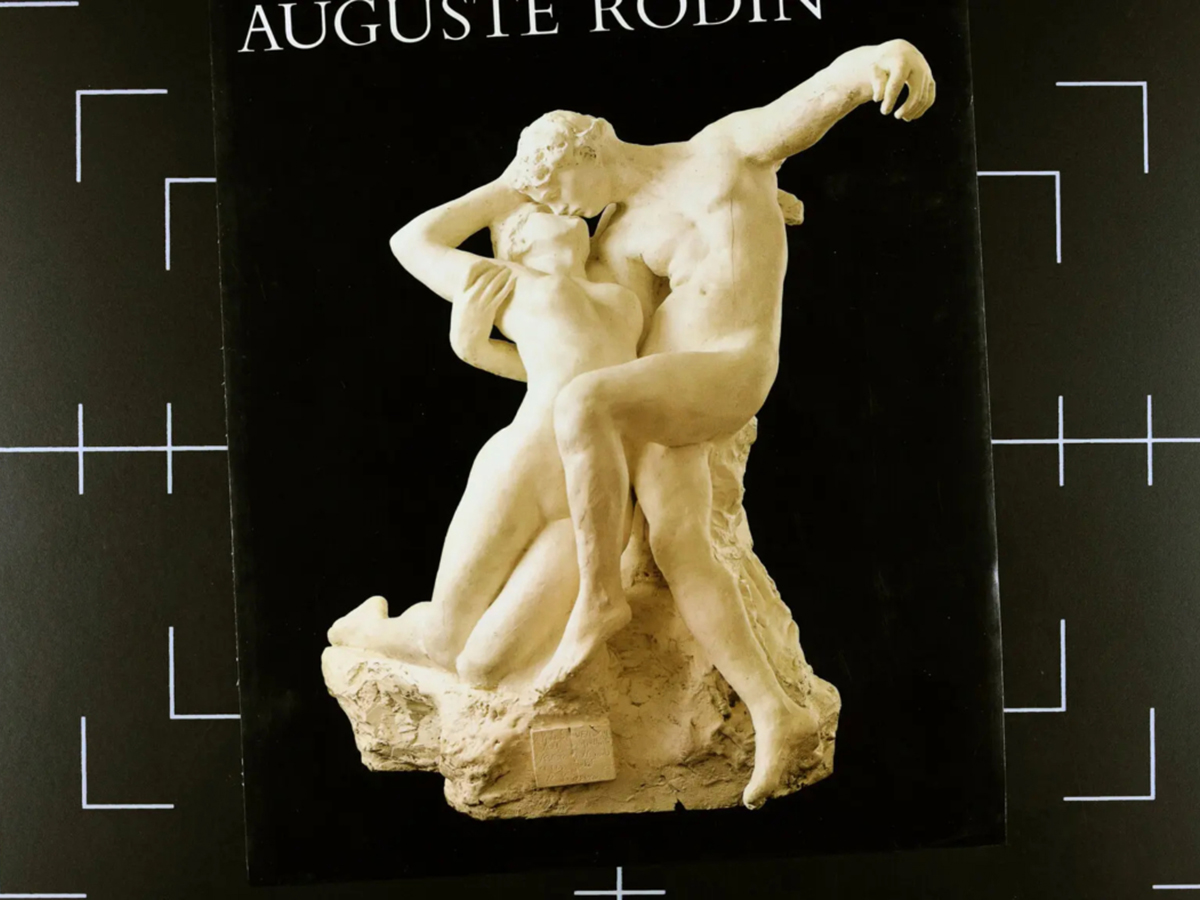

The exhibition’s title nods to Time-Life Books, a now-defunct purveyor of direct-mail encyclopedias, catalogues, and how-to manuals that, prior to the rise of the Internet, were familiar fixtures in American middle-class homes. The conceit of the videos is that we are looking at these volumes from the perspective of a high-speed scanner as it captures their pages at a rate of eight frames per second—too fast for the human mind to fully comprehend, but sufficient for creating a permanent digital record that renders the print publication superfluous. “Time Life,” 2014–22, bears traces of Thomson’s earlier films without remaining tethered to any specific era. The sentences in Volume 4. 1000 Questions, 2016–22, flash by with the same semisubliminal flicker as the text in Paul Sharits’s Fluxfilm Word Movie, 1966. The animation effects of Margo Leavin Gallery reappear in Volume 2. Animal Locomotion, 2015–22, as photographic sequences of leotard-clad models demonstrating 1980s aerobics routines. Particularly enthralling is Volume 5. Sideways Thought, 2020–22, which cycles through the celebrated oeuvre of Symbolist sculptor Auguste Rodin. Set to an original score composed by Ernst Karel, the sinuous surfaces of The Thinker and The Kiss quiver and come alive.

The “Time Life” series seems to belong to the emerging genre of “desktop videos” (or perhaps, pace Leo Steinberg, “flatbed videos”), such as those by Camille Henrot or Sara Cwynar, wherein disparate agglomerations of text and media slide across the screen to the hypnotic rhythms of a pulsing soundtrack. Alternately, Thomson’s allusions to book scanners connect the videos to investigations by Trevor Paglen and the late Harun Farocki into “machine vision”—images intended for technical devices rather than human eyes. That is, “Time Life” may be less concerned with the past, or even the present, than with an increasingly plausible future where traditional receptacles of memory are supplanted by server farms for raw data. Watching Thomson’s videos, I suddenly recalled a headline from the routinely oracular satirical newspaper The Onion: “Google Announces Plan to Destroy All Information It Can’t Index.” The article, I later checked, was published in 2005.