February 17, 2023

Download as PDF

View on ArtReview

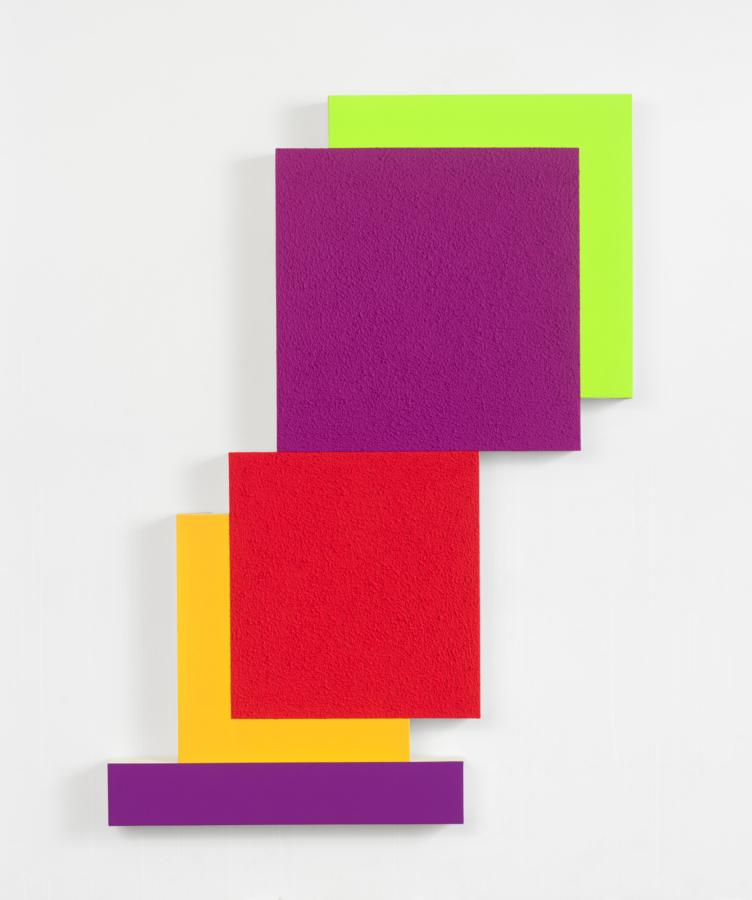

Peter Halley, White Noise, 2022, acrylic, fluorescent acrylic, Flashe and Roll-a-Tex on canvas, 216 × 151 × 10 cm

A new show at Karma, Los Angeles, foregrounds some of the most balanced unbalanced paintings out there today

It didn’t seem possible that ‘unbalanced’ would ever be used to describe a set of Peter Halley paintings, but – wait, just kidding, it still doesn’t apply, not in the case of these ten new paintings shown at Karma’s flawless space in Los Angeles. They may be the most balanced unbalanced paintings out there today. In them Halley’s signature conduit and prison-cell geometric motifs have been reconfigured into shaped canvases that bring to mind the careful yet playful joinery of Memphis-style furniture, not to mention videogames like Tetris or, better yet, Tricky Towers. (Strikingly, the conduits have been removed, suggesting that the structural fitting-together of the paintings is now where all the connectivity operates.) Many of these new paintings may be top-heavy, but surely none of them will topple. Some of them look like they’re levitating, but they are still heavy, no matter how flamboyant their colours and configurations may be.

Writing in 1993, I marvelled at Halley’s ability to shake off, but not totally abandon, the 1980s ‘endgame’ death-of-painting trap of the geometry-as-prison mantra by changing his titles from, for example, Black Cell with Conduit (1986) to Teen Dream (1992). His titles have always mattered, and in the case of the new paintings (all 2022) they seem to relate to recent mainstream, but not blockbuster, movies: Babylon, End of the Road, Slumberland. (I have a feeling the titles could be the best thing about these films.) It’s a bad joke that the paintings could be called literal block busters, but I’m making it because despite the literal reshaping of their supports they continue to prioritise and power up form as the tool to manifest Halley’s symbolic content of architectural and social circulation and containment. That content is extended to the legacy of mono-chromatic painting itself by two especially jerry-rigged works – Brazen and White Noise – that forgo the cell image and stick to squares and rectangles (and right angles) of various solid colours, some of which are particularly resplendent in Halley’s classic, often called

‘suburban’, Roll-A-Tex paint. They bring the entire show home.