December 7, 2023

Download as PDF

View on Turning Point

Take a quick look at an American “type B” A/C power outlet. How long until you see those three little openings—two flat vertical notches above an elongated half circle—as a human face? Not long. The intensity of our semi-conscious urge to anthropomorphize even the most unpoetic, matter-of-fact elements of our surroundings is indeed shocking; we’ll take meaning wherever we can find it. Likewise, non-mimetic art, especially abstract painting, has, since its inception, been pitched against a single adversary: the arbitrary, by which any principle or structure will do, so long as it’s something. Textbook1 art history of the nineteenth century, going into the twentieth, has it that the elements of artmaking were, through successive movements, freed from depicting objects—the world around us—in favor of isolating and enhancing “expression” as a stand-alone dimension. In painting, Post-Impressionism broke color and mark loose from the medium’s long-reigning mimetic parameters. Fauvism, and Matisse himself, continued from there until others like Kandinsky soon bore “pure” abstraction, which finally banished any “recognizable,” world-bound content from the canvas entirely.

Painter Mark Grotjahn is known for his large “abstract” paintings and unabashed exploration of paint application as a proprietary idiom. His is a painting of the “mark,” or “mark making,” to be more exact—a technique often treated as the stamp of “expression” and abstraction, those two concepts that in this gesture are compounded into one easily traceable development. Grotjahn’s work has, in general, redeployed the generous marks of gestural abstraction pioneered by the likes of de Kooning—the kind of abstraction that always, still (and contra Clement Greenberg, the apostle of the “purified” medium) hovered at the base limit of legible figuration, or, at the very least, of worldly representation. It is this last aspect of the Dutch American master’s work that resonates most with the distinctive element in Grotjahn’s project: Grotjahn’s “face” paintings (not to mention his “mask” sculptures) almost always, in one way or another, come to rest upon some basic unit of anthropophizog legibility. The main reason: bilateral symmetry, an almost unfailing orientation for Grotjahn. Going beyond “the figure” (i.e., the face), Grotjahn has more recently produced many abstract canvases, which ultimately resolve themselves along a horizontal axis into “landscapes” evocative of the Romantic “sublime.” Karma Gallery has showcased another different, but loosely concurrent, body of much smaller-scaled work: his single “skull” paintings.

These little “vignettes,” which Grotjahn has been producing since 2016, retain many of the artist’s signature stylistic elements. The paint still comes mostly straight from the tube in vibrant, “classic” colors (the kind that supplied mimetic painters’ mixing palates for centuries). Its application still looks as loose and spontaneous as it does in his “faces” and “landscapes”; in fact, here, it’s even wilder. Though the “faces” and “landscapes” often cultivate an overall sense of vibrancy-amid-chaos, they are actually elaborately constructed across layers of carefully nestled, adjacent “rays”—an operation that, at its most characteristic, is rarely performed with surgical neatness. With the “skulls,” Grotjahn has kept his trademarked corrugated cardboard supports, giving these works too a sense of non-archival immediacy. The cardboard lends them an unsentimental, but no less substantial, presence that can stand up to their heavy-handed—often just squeezed-on, and then just slightly brushed over—style of paint application.

Untitled (Skull VI 48.32) (2016). Oil on cardboard, 6 1⁄2 × 4 7⁄8 inches, 20 × 17 inches (framed). All images courtesy of Karma.

With many of his earliest “skulls,” Grotjahn overwhelmingly likes to let multiples of a heavy mark of color—streaks—delineate his forms. Untitled (Skull VI 48.32) (2016) may be the smallest, simplest, and the most direct work in the show, at least as far as palate is concerned. A contrast of red and green planes divides figure and ground, while thickly applied lines—set in wonky, horizontal parallels of pure white (a vague, if not generic, “tribal” motif)—sketch the skull’s general form and physiognomy. Its white almond-shaped eye sockets are outlined with the same red, building contrast through amplification, and resolving below in a red nasal cavity that is set slightly off-center, anchoring the little composition.

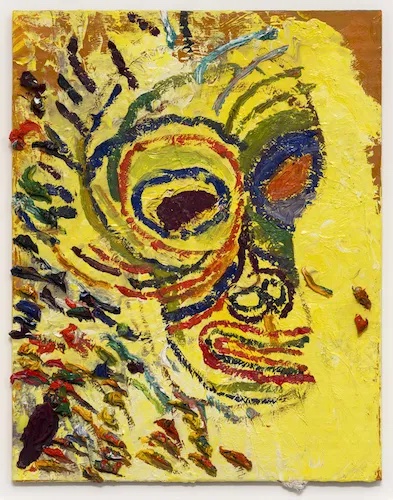

Untitled (Skull) (2019). Oil on cardboard, 12 × 9 1⁄2 inches, 25 × 20 5⁄8 inches (framed).

Untitled (Skull) (2019) catches the artist using his most descriptive linework. However, taking a cue from Matisse’s “systematic” Fauvist sensation The Woman with Hat (1905),2 Grotjahn also simultaneously lets color disparity and plane build the features surrounding the right eye socket. The socket’s architecture vibrates outward from a pinkish orange almond encircled by a halo of blue, which is banded at top and bottom by two shades of green. The top shade, an otherwise ugly olive, drives—with the help of four jibing bands of color above—a delicate, little cascade down the upper-right quadrant of the picture. The left socket, in what is perhaps an unintentional pun on medical terminology, emits rings (orbits)—some broken, some fully intact—of red, blue, green, and orange, done more in keeping with the rest of the skull’s line-based execution. All of this is staged on a lemon-yellow field, which is swept over with a blizzard of variously colored “toothpaste stripes” at the bottom left. The stripes turn to dark mauves and blues as they continue up and around the outer “cranium,” radiating a choppy, hair-like halo that seems to be the one feature nearly all the works share.

Untitled (Skull) (2019). Oil on cardboard, 10 × 8 inches, 23 5⁄8 × 20 1⁄8 inches (framed).

Untitled (Skull) (2019) announces the major pivot in the artist’s work during the seven-year span of the series. There, the skull subject has been almost entirely diffused and Grotjahn plays with the limits of his subject’s recognizability. By extension, the entire painting has been noticeably flattened. This evacuation of depth from the painted canvas results from of a procedure that approaches the sensorially effective systems of optical approximation developed by Post-Impressionists like Seurat. In the Divisionist master’s estimation, single units of color deposited evenly and adjacently across the canvas, by producing localized contrasts, achieve something like retinal atomism—one that nevertheless coheres, and can even mimic, if not entirely replicate or magically reconstruct, the manifold operations of the human optical sensorium as it interacts with light. Painting pure form became an act of brutality: a contour on the canvas came to be regarded as a kind of violence done to what the eye “really sees,” intrusive incisions rent upon the grid of scintillating sensations that is our sight. Thus, the marks were kept small and discrete, and continuous lines were shunned. Here, Grotjahn is all about contours—or streaks, rather. In fact, they become his painterly datum of choice. To the extent that contours writhe, in sequence, across the canvas, they nullify depth, almost evanescing into each other, while still oddly providing reference to a degree that is so basic as to be semiotic. Two deep red circles at the middle of the picture form a nasal construction. The rest of the painting seems to wiggle out from there. The red circle to the right meets a line of lighter red to form the bridge of the nose that is also then a “6.” Yellow eyes appear further above like two rocks dropped in a pond. A band, formed by two parallel rows of staccato-hatched teeth, is laid underneath. The worm-like lines all evanesce outward until finally diffusing at the outer edge of the canvas, revealing a white background.

Untitled (Skull) (2023). Oil on cardboard, 16 × 12 1⁄4 inches, 28 3⁄8 × 22 5⁄8 inches (framed).

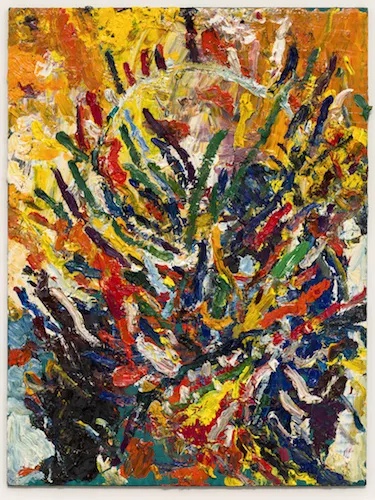

Two showstoppers from 2023, both untitled, turn up in the gallery’s backroom. Both are, at first sight, messes of blaring, intense color—primaries and secondaries (plus white… and black). Each looks equally sinister once the eye begins to parse out an image from the elements on offer. In the painting on the right (done on two pieces of board, one slightly smaller and overlaid atop the other), thick and dauby mark making mumbles out garbled descriptions of eye sockets, a nasal cavity, and cheekbones, among all the colorful noise, only to disintegrate into gauzy negative space. A non-integral band of pink pastel and light grey to the left of the figure helps maintain some hushed sense of figure and ground. Its teeth are, in contrast with the rest of the raucousness, rather clearly delineated—little white “Chicklets” contoured with dark grey, set low and at a slant as if the mouth had broken loose and fallen free of the whole. The painting to the left is a fiery riot with oranges, reds, and yellows at the fore. The marks all share an unambiguous trajectory upwards. Like a cartoonish depiction of Satan run over by a truck, this devil might have horns, pointed brows, and a Dalí mustache in there somewhere. Look hard enough and you might even find a disarrayed snarl of white teeth here too.

Untitled (Skull) (2023). Oil on cardboard, 16 × 12 1⁄4 inches, 28 3⁄8 × 22 3⁄4 inches (framed).

Why skulls? They are the most basic structure of our visage, long the locus of “expression” in pre-Impressionist painting going back to the Middle Ages. They are the seat of our cognition, the home of the mind, and, by extension, the origin of human enlightenment. Since the Renaissance—and up to, and including, the Enlightenment proper, artists (and their compatriots, anatomists) studied the skull as a near-divine object, a miracle of creation. Formally, it is reducible to a few sockets and slits, an icon—in the earthly, communicative sense. As a symbol, the skull has gained notoriety, and not only because of the Jolly Roger: Hitler’s SS wore the Totenkopf while serving as the instruments of rabid ideology and absolute evil. Now, as a semantic vector, the skull’s cultural valence traffics in much more diffuse expressions of aggression, strength, and deathlessness found, for example, in Punk Rock and biker paraphernalia—offensive, perhaps, but ultimately harmless. Still, why paint them? Why would Grotjahn land on this form—the skull assumed as a basic set of components endemic to any angry, adolescent chicken-scratch—as an underlying structure for his various, and very engaging, little painterly endeavors? For Hamlet, the would-be King of Denmark, the skull helped him foster a pose of Baroque contemplation, if not inaction. An older Cézanne took up the skull as a subject as he himself began to decline; the motif was worked out simultaneous to his redoubled efforts to consolidate and concentrate his painting as a system. Grotjahn moves in the opposite direction of this cerebral locus toward something freer. Free, in the way our minds—in all their cognitive intricacy—simply land on a face when we see an electrical socket, free and, even… fun.

- See Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, David Joselit, Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism, vol. 1, 2nd ed. (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2011), 70–77.

- Ibid., 74–75.