January 8, 2024

Download as PDF

View on Art Basel

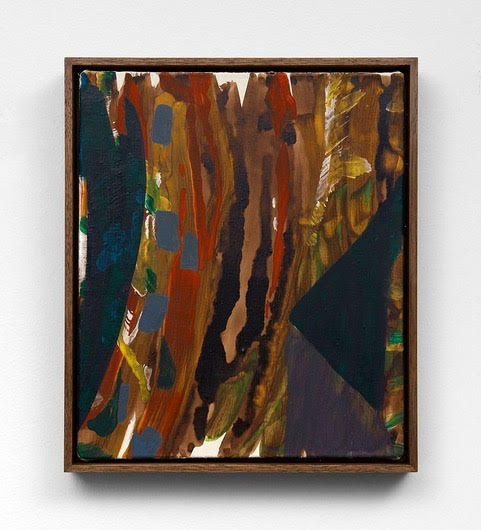

Photo by Joss McKinley for Art Basel.

In just a few years since graduating from art school, the London-based artist has shot to international stardom. He’s now set his sights on creating a new hybrid art space in the Whitechapel district.

‘A door can be a metaphorical way of telling somebody that maybe they don’t belong in a place, or that they have to have the keys to get in. What is the design that says, “You’re allowed to be here”?’ Such is the question preoccupying the artist Alvaro Barrington as he shows me around a late-19th-century, dreamily neo-Jacobean assembly hall on a site he has recently purchased in Whitechapel, east London. It was once the location of England’s first free school, established in 1680 by a local parish rector. When the school was relocated to Essex in 1965, its buildings continued to serve the neighborhood – becoming home to trade union offices, a welfare advice bureau, and a computer literacy scheme, then later a music venue and finally a youth center – until the doors were shut to the public in 2017. This is something the artist now intends to rectify.

Since graduating from the Slade School of Art, London, in 2017, Barrington has charted a meteoric rise that’s seen him work with some of the world’s leading commercial galleries, stage a rapturously received solo show at the South London Gallery in 2021, and become the latest recipient of Tate Britain’s prestigious annual Duveen commission – more on which below. He is primarily a painter, although this designation struggles to contain both the range of the materials he employs (which commonly include burlap, concrete, yarn, and found postcards) and the way the images he creates often break out into three dimensions and become embedded in installations (his first institutional solo show, at MoMA PS1 in 2017, saw him present what appeared to be a wholesale recreation of his studio space).

Born in Venezuela to a Haitian father and Grenadian mother, the artist was raised in the Caribbean and then Brooklyn and is now based in east London. ‘Part of my identity is that I come from an immigrant working community,’ he says, and this ‘emotional narrative’ informs his interest in Whitechapel, a gentrifying if still largely working-class district with a long history of absorbing new arrivals to the city. As Barrington puts it: ‘You had the Huguenots, the Irish, the Jews, the Bengalis, all these different groups of people who said to themselves, “This place makes me feel welcome.”’

Having established a studio across several of his site’s Regency-era school rooms, he is in the process of transforming the Victorian assembly hall into an event space (under his auspices it has already hosted the fashion designer Jawara Alleyne’s Spring/Summer 2024 collection show). This will be complemented by what he calls ‘a kitchen, not a restaurant,’ designed to promote free-flowing interaction among its patrons (he cites the Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija’s practice of bringing people together through the sharing of food as an important touchstone). The menu? ‘Modern versions of working people’s cuisines.’

A garden is being planted next to the assembly hall, and Barrington is in dialogue with community leaders, a local preschool, a neighboring block’s tenants’ association, and ‘folks who’ve used this building in the past,’ to explore ‘what they’d like it to be.’ One thing is certain, it will be renamed Emelda’s, in memory of the artist’s late mother. If this nascent project has elements of a social enterprise, then Barrington also sees it as an extension of his studio space, saying that what he works toward in his art is ‘an emotional understanding of how people exist. So this is the perfect way to bring the world to me.’

The idea of home – lost, found, remembered, reimagined – is central to Barrington’s practice, and his two most recent solo exhibitions cast lingering glances back at his childhood and teenage years. For ‘Grandma’s Land’ (2023) at Sadie Coles HQ, London, he presented three shack-like structures that supported paintings soaked in the light and heat of the Caribbean, featuring motifs of hibiscus flowers, huge orange suns, and a carefree woman splashing in the waves of a blue-green sea. His current show at Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris, evokes a very different environment: New York in the 1990s. This was a place and time in which, as the artist notes, there was a ‘mass incarceration’ of Black youth, and politicians such as Rudy Giuliani and Hillary Clinton framed ‘my friends, my neighborhood, my community’ as a threat to more privileged American lives. Reflecting on this era, and looking at Pablo Picasso’s early paintings of working-class Parisians, he began to ask himself, ‘What’s my Blue Period? How can I make art that feels honest to the way we understood ourselves?’

The answer was provided by Truman Capote’s novella Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1958). In its protagonist Holly Golightly – who Barrington sums up as ‘a 19-year-old girl who moves to Manhattan, reimagines herself as a high-end sex worker, and becomes the center of everybody’s conversation’ – he detected a kindred spirit to the Brooklyn teenager he once was. The artist recalls how, often having slept on the subway, he would exit Prince Street station early in the morning and wait for SoHo’s stores to open, so he could buy ‘a fresh shirt, or new jeans, and change into who I wanted to become, or what I wanted to present myself as.’ (Golightly, of course, famously did her window shopping at the Fifth Avenue jewelers Tiffany & Co., the only place where she believed ‘nothing very bad could happen.’)

Featuring 1990s Black icons, including the rapper Tupac Shakur and the singer Mary J. Blige, a number of the paintings in Barrington’s Ropac show are displayed behind glazed cardboard storefronts, like objects of desire that lie just beyond our reach. Perhaps the most affecting work, however, consists of a quintet of closed, wall-mounted metal shutters, of the type the artist encountered as an adolescent, gleaming with promise in SoHo’s morning light. To access them, visitors must first step through a heavy chain curtain, as though entering a new world, a new life. These shutters, Barrington says, are ‘my streetscape, my landscape painting,’ with a genealogy that includes the sacred vision of Piero della Francesca’s The Baptism of Christ (1448-50), the grand, Manifest Destiny-infused American vistas painted by the Hudson River School, and the diffusing fields of form and space in Mark Rothko’s abstract canvases. The artist, who sees the work as essentially ‘spiritual [and] all about anticipation,’ plans to make a smaller version of it that will hang, totem-like, in his Whitechapel studio.

In May Barrington’s project opens at Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries, which will see him take on the institution’s 300-ft-long, barrel-vaulted neoclassical central space. He can’t disclose any details right now, but he says he’s been looking at the different formal decisions made by previous recipients of this commission (who include Mona Hatoum, Martin Creed, and Phyllida Barlow), and that he sees his task as making ‘a brand-new interjection.’

Barrington is more forthcoming about an as-yet-unrealized idea he has for an exhibition themed around the seminal 1990s New York hip-hop collective Wu-Tang Clan, whom he describes as ‘a perfect North Star for creating a body of art.’ Having invited one of its members, Ghostface Killah, to perform at the opening of his 2022 solo show at Blum, Los Angeles, the artist is intrigued by the different personalities that make up the Clan, and how they reflect the breadth and complexity of urban experience: ‘You can’t be more punk or more avant-garde or more Baroque or more Dada than [the late] Ol’ Dirty Bastard. [Then there’s] the charisma of Method Man, the cerebral-ness of RZA and GZA, the braggadocious-ness of Raekwon… .’ Named after a Hong Kong martial arts movie, Wu-Tang Clan are what Barrington terms an ‘embodiment of locality, but also global-ness.’ We might well say something similar about the artist and his work.