March 2024

Download as PDF

View on The Brooklyn Rail

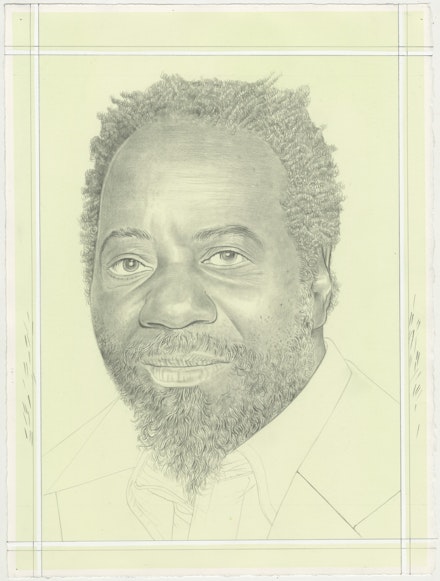

Portrait of Ouattara Watts, pencil on paper by Phong H. Bui.

Ouattara Watts is a painter whose works are infused with abstraction, symbolism, history, and alchemy, which embody a fusion of cultures throughout time and place. Painterly, gestural, and tactile, his work focuses on the crossover of semblances that we share as humans. It is how we relate to one another despite our differences which interests Watts, and feeds his symbolism and philosophy in life. His work seeks to have no borders where he moves and embeds painting, drawing, fabric, and photography seamlessly while working simultaneously on multiple industrial canvases ready for his compositions. Hugely influenced by music, his life is an ongoing play of rhythms that follow a feeling for improvisation closely related to that of jazz. From Côte d’Ivoire where he spent his childhood, to Paris where he studied at the Beaux-Arts, he then settled in New York in 1988 after his friend Jean-Michel Basquiat encouraged him to pursue his painting here and New York has embraced him as an influential artist ever since. Karma gallery first exhibited his recent work in 2022 prior to the current show in their LA space this year. This conversation (translated from French) between Ouattara Watts and Rail contributor Amanda Millet-Sorsa took place in his Bushwick studio located near the Morgan Ave stop on the L train on a sunny afternoon over espresso.

Rail: When you were working towards the current exhibition at Karma LA, was there a specific spark or something that happened during the process of working, that steered you towards any specific symbolic imagery for this group of work?

Watts: I thought about a potential new series of images and ideas. These you cannot control—that is the act of creation. When you’re in front of a painting, you don’t know what might happen, and I don’t employ sketches. I am very direct. It’s like music and when I play music, it’s like improvisation in jazz, you just go at it so one plus one doesn’t make two, it makes three, because you have the swing to the rhythm. For me, that’s painting! When I’m working, I almost spend all my time dancing! I dance—a lot.

Rail: Do you also work on the floor?

Watts: I do. It’s very physical since I fluctuate from working on the floor to putting the work on the wall, then back down on the floor. It’s a choreography.

Rail: That makes sense, as I notice there are traces of shoe prints on your drop cloths, the substrate for your paintings, much like the presence of your hands, which can be observed in the tactile movements of the paint pigment.

Watts: When I place the drop cloths on the floor, I also like to dance on them as if I’m going to attract or generate different energies, and then afterwards, those energies continue and might transform through the use of my hands, brushes, and other materials. I love starting out with a rhythm that stems from an organic and bodily source. I work a lot with my hands and very little with brushes.

When I get to the studio, I always put on some music, and let it dictate my body. Once the body gets into the rhythm, the painting really begins. We remember in the 1910s, for artists in Europe, it was absinthe, but for me it is music. Music really is an essential part of my work.

Rail: I know that you admire the music of Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Charlie Parker…

Watts: Yes, absolutely, especially the late Ornette Coleman who was a friend. I really love jazz. I had a studio on Lafayette Street, someone had lent me a studio in the early nineties, and Ornette appeared suddenly at my studio’s door. He was looking to buy a loft. He said, “You Ouattara?” I said “Yes…” [Laughter] I didn’t know him at the time, just his music, but he had already seen my work which was exhibited in the New Museum, the Vrej Baghoomian Gallery, University Art Museum, Berkley and others at the time.

Also, one of my first trips with Jean-Michel Basquiat when I first came to the US in 1988 was a surprise trip down to New Orleans. It was Jean-Michel, myself, and Kevin Bray. We had a wonderful time in New Orleans listening to jazz right next to the Mississippi River and realizing that Africa is just over the Gulf of Mexico and North Atlantic Ocean, and here we were in the United States!

I remember there were groups of musicians and orchestras that would pass through rather than individual musicians. We went just to listen to music, wandering and dreaming on the Mississippi River.

Rail: Music, it seems, is central to you as a source of creation. Did you know other composers or musicians in the years you have lived here in New York?

Watts: When I was still in Abidjan, my good friend Alpha Blondy played reggae music. We lived in the same neighborhood, and we got together with other people also practicing music. Later, I got to know Salif Keïta from Mali. In Paris, my friendships with musicians grew as well with Fela Kuti, and then in New York, Ornette Coleman was a friend, and then much later I followed the music of Henry Threadgill and we got to know each other. Music and musicians have always been part of my life. I’ve been to concerts at Smalls, Blue Note, Paris in Harlem, and Shapeshifter Lab in Brooklyn.

Rail: Did you ever want to collaborate with musicians?

Watts: That’s my dream. I had a project with a musician called Keziah Jones, from Nigeria, but nothing yet happened. Here in the US, there is another musician, Melvin Gibbs, who I consider one of the most talented young bass musicians in jazz. I have seen him in recent years in Brooklyn at Weeksville Heritage Society. I’d love to collaborate with him.

Rail: What would a collaboration with a musician or a composer look like?

Watts: They’d play and I would paint, for we both improvise simultaneously. When I was seventeen, eighteen years old, I already dreamt of doing something like that because I come from Korhogo, where both of my parents were born; it’s a city in northern Ivory Coast, where Senoufo and Bambara are spoken. There you can see a ceremonial dance called Boloye, the panther dance, where the dancers wear costumes dripping with paint, which makes me think of Jackson Pollock paintings. Along with the dancers, there are about sixty musicians that play bass at the same time; imagine that, sixty basses! I would love to work with those people and I think it’s going to come. That would be something! Yes, in fact, it would be incredible.

I love music. I practiced music a bit, but it really wasn’t my thing. I stayed with painting because I could feel it was my thing. You know, when I was a kid, we were cradled into music. You’re really immersed night and day—you sleep in the music, you wake up in the music, you really are in the music, it’s part of life’s fabric. Your neighbor might come to you the day after you’ve been playing some music and comment, what was the piece you were playing between 2 and 3 a.m. last night, what was the name of the group or title of the song? You can get a sense of the intensity. Music is so immersive that no one would complain when you’re playing your music. It’s the contrary, they’d appreciate it. We are cradled into music all of the time.

Rail: It’s a poetic phrase: to be cradled into the music. Here, in the US, it’s the opposite: if your neighbor hears you at 2 a.m. playing your music, they’d come knock on your door or call the cops to do it for them…

Watts: [Laughter] Music did me a lot of good. When Jean-Michel went to Africa, he went all the way there to the North where I’m from, to listen to music.

Rail: Do you work in series? What are your views of a finished painting?

Watts: I don’t like to work in series, so I don’t think I’m finished with this group of work. I’m going to just keep going until I may slow down in a couple months and then resurge again.

In any case, a painting is never finished. You feel it or you don’t. In two, three years, afterwards, you’ll know whether it was any good. You also have to leave it alone because it can be ruined. But at the same time I’m not afraid because I welcome challenges. So as long as the painting is in the studio, I can keep working on it. Even if it’s no good, I can just erase it, which gives it more body and enriches the material, and one day the work will explode. There are some paintings that have also stayed in my studio five years without being touched, and then one day, a thought comes, and I go working on it. In two weeks, it will be resolved, but it took me five years! In my way of working, there are no rules, no direction, there are thousands of possible directions when you start a painting. If you paint an object representationally, like a mug, or a bottle, for example, I think it’s different, but if it’s abstract then all kinds of ideas as images can come to you. There is a lot of energy.

Rail: Your dedication to painting is immense, yet you have exhibited your photography recently, and you also make drawings. How do you relate these different material practices to painting?

Watts: Drawing is treated similar to a meditation. I use pastels and watercolors on paper, and then once I begin, I let the images and the water flow into a rhythm like a river. I can sit down and draw for hours and hours, which I also like to do when I’m traveling.

Rail: What about your photographs? How do they relate to your creative thinking?

Watts: I am a painter, so I relate to photography through the eyes of a painter. Some of the first photos were taken when traveling in Colorado for a show I had there organized by Raymond Foye with Baldwin Gallery in 1998. I take a photo when something speaks to me, much like how a textile might speak to me when constructing an image, a painting. A photo will be used like collage, the image can be scaled up or left in its original scale. It really happens in the moment, as I don’t have a particular subject that I’m after.

Rail: You have mentioned that you make your own paintings with some unusual tools. How would you describe your painting process, which is so distinctly different to the next?

Watts: First of all, my main tools are my hands. I had to work on the floor for this other one because of how I work the material with my hands in a similar technique to how Sudanese house facades are built. This work here with a collaged photo of an African statue is one of the photographs I took at the Metropolitan Museum. It came to me just like that, and I glued this to the canvas directly. In this way I work more quickly. It’s about composition and I follow its journey. I hadn’t used photos in a long time, so I wanted to come back to it because in the United States they don’t really know this side of my work in paintings (except for perhaps two to three paintings from Vertigo, the exhibition curated by Vladimir Restoin Roitfeld in 2012). I have shown them mostly in Rome. I started this kind of work with photo and fabrics at the same time as the ones like La Porteuse de Connaissances (2023) in LA. I can easily go from this kind of work to another, just like when you get up in the morning with your left foot then your right foot.

But sometimes I use all kinds of brushes and at times even brooms. I’ve used this little broom [goes to studio to show me the small broom a foot in length of African origin] and I used it as a brush on The secret house the painting yellow with the house (2023). I also love letting shredded paper bathe in water and disintegrate into a pulp, into which I mix in color pigments bought from Kremer Pigments, along with Golden Gloss Medium, as a binder.

Rail: To what kind of consistency?

Watts: Like a thick sauce.

Rail: For many artists, everything begins with the deep knowledge of how the materials get materialized. Could you describe how your love for music and your sense of the materials get infused?

Watts: When I arrive at the studio, I play my music, I have all my sauces, and then I can start to move, to see, to listen to the music and then at some point I don’t listen to the music anymore. I am elsewhere. There is a magical moment that occurs between yourself and the canvas. I think every artist will tell you this, but nobody can describe it. Nobody. The one who describes it is probably a liar. I should mention I use a lot of different fabrics and textiles with patterns as collages, which began as early as my first works when I came to New York in 1988 and it continues to this day.

Rail: Do you collect them a little from everywhere when you travel?

Watts: Yes, everywhere I go, I come back with fabrics. When I lived on Broadway, there were fabric stores right in front of my home, and all I had to do was cross the street and sometimes I would go to the Garment District in Midtown for others.

Rail: However, the work in this show seems to be without the use of fabrics?

Watts: That’s right, there aren’t any! It’s mostly drop cloths, industrial canvas.

Rail: Do you find that this polyvalent way of working surprises people when they get to know your work?

Watts: It surprises me. I love it when it surprises me, but I think that when you’re an artist, when something surprises you, it’s usually a good sign! It HAS to surprise you.

Rail: Syncretism is often noted as a principal subject of your work as seen through combined symbols of spirituality and faith. How would you describe your own take on syncretism?

Watts: I was very lucky in my life to have been born in Africa and that one of my great uncles was a shaman. I started learning from him as young as seven, eight years old, and he would teach me about the stars, the universe, and what it means to be an artist. Like most children, I scribbled and drew, but he would tell me when I was older that if it is really what I wanted to do, I absolutely had to understand certain primordial things as they relate to the cosmos. That is what it means to be an artist, he would say. As a kid, I would just listen. It was later, around seventeen years old, that I really started to understand it was my thing and I wanted to pursue it. I went back to see him and then he started to really load me with ideas and everything. One has to understand that to be an artist, one cannot be the artist of the tribe, of your city, nor of your country, but an artist of the cosmos. The artist is the guardian of the cosmos. This is how my education began and everything else followed.

Rail: I love that the artist is the guardian of the cosmos!

Watts: I was very lucky to have this shaman great uncle who imparted his wisdom to me. Since I had not stopped painting and working from a young age, the more I worked, the more his words became important to me. I remember learning about art by reading, looking at art in books in the French library in Abidjan. There I discovered Picasso, Matisse, Brâncuși, and Modigliani, and many other European artists who were completely inspired by the art in Africa. So for me it was a signal—gling-gling—and I thought, wow! As I became more intrigued, I needed to go to Paris because all of these great artists were there, then. I wanted to go elsewhere because these artists came from elsewhere. Evidently, later, the more I know, the more I further my research, I would eventually land on antiquity, ancient civilizations and learn about ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia…

Rail: It is in this moment that you start to realize that there is a fusion of different worlds. When I think about what syncretism means, it seems that it comes from different places and that on one hand it is a fusion, stemmed from curiosity, an expansion of the mind and senses; it’s perhaps the case of Picasso, Matisse, Brâncuși, Modigliani, and many others you mentioned. But it’s also, historically in ancient civilizations, the results of wars, dominance, bloodshed… I understand fusion also to be the beginning of something new: it can be a form of survival, of protecting sacred elements that can be hidden if we think about different cultures and faiths that have survived through cultural fusion. As you embrace it in your art making, does it get assimilated in your life as well?

Watts: Absolutely, it’s how I live my life. For me, this fusion is my life, and it’s how I live my day-to-day. When I see what happens in the world, all the wars, the universe is ailing, there is something that isn’t right; we have a problem, we haven’t finished with the wars—the history in Germany, and now the war between Russia and Ukraine, between Israel and Hamas, and endless civil wars happening in Afghanistan, Sudan, Syria, and other countries in Africa as well, it’s everywhere… As artists all we can do is to raise awareness with our people; we have to keep working, and showing our work, so that people might close their eyes and then urge them to open their eyes again and learn how something could go as much in the positive direction of freedom of creation as in the negative direction of oppression. We all know it can go either way, it is up to us to make the choice. Fusion is my life, and that is how I have chosen to live. It’s why I need all my time to make paintings, more paintings, as many as I can in my lifetime.

Rail: We can identify references, symbols, and images deriving from ancient Greece, Mesopotamia, and Egypt; were there symbols or fusions that you’d embraced or adopted when you arrived to New York, and the US in general?

Watts: In New York, it’s more about the energy which brings different cultures together. There isn’t one single image that inspires me in New York, as it’s really about the strength of the artistic community in cinema, music, dance…

In the United States, it’s the expansive space. Be it Colorado, Arizona, or California, where there are mountains or mounds of earth, which reminds me of Africa, especially when the earth is red like in the Grand Canyon. Oh là, là, what a space. I understand how Jackson Pollock lived through this space, when his father worked as a land surveyor in Wyoming, Arizona, and elsewhere in the Southwest, as it had a profound effect on why he works the way he does. The space is open so I learned a lot about art in the United States as well. Or the desert near Palm Springs in California. The desert is crazy, you might as well be in Mali.

Rail: You felt as though you were returning to your childhood?

Watts: Completely. Like a dream. I saw that Max Ernst had lived in Sedona, Arizona with Peggy Guggenheim, and you can see how the Zuni and Hopi cultures had influenced his imagined landscapes. Perhaps one day I would go there and settle in Arizona. I would absolutely live in the desert. I spent my childhood in the Savannah and then when I went to Mali, I discovered the desert, both are about space.

Rail: I could see you there since in your work we see big expanses of space in addition to the monumental scale. At any rate, when we were walking together around your current exhibition, you remarked that the crown of the Pharaoh appears as a recurring symbol in this work as well as the Senufo ladders from Western Africa, the cacao, and numbers. Can you elaborate more on their presence?

Watts: It’s part of the early history of humanity. Lower and Upper Egypt was a fusion between Greece and Egypt during the time of Pythagoras, which is why I keep returning to it. I had worked a lot on this in the 1980s and then stopped for twenty years or so and picked it up again since 2020. There are symbols that are not necessarily recognizable since I modify them, and I create my own language too, as well as those people recognize like letters or characters, sentences, African symbols, Catholic symbols… it goes on. When I don’t have an image and I don’t know what to paint, I go to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and there I go to different wings to look at different things, from Egyptian Art, Arms and Armor, Greek and Roman Art, to Medieval Art, fashion, everywhere!

In fact, I made a series of photographic portraits of certain objects, masks, and armor—Greco-roman. These were then digitally printed in large formats and exhibited in Rome at Magazzino gallery. In this sense, photography is an integral part of how specific images can be filtered and modified later into symbols for painting.

Rail: I now can see the symbol of the Pharaoh’s crown implies an allusion to power, compared to the Senufo ladders or Brâncuși’s infinite ladders, which have a more spiritual connotation of ascension.

Watts: To me the crown again is about history. It references the origin of our human species and early ancestors having roots in Lucy (Australopithecus) who lived in Ethiopia 3.2 million years ago.

Rail: If we come back to the universal idea that unites us all, we would recognize the first steps on this ladder towards ascension is constantly finding ways to ask questions why we’re here. Could you share with us the function of the house inspired by Malevich, which appears in Spiritual Gangster 01 (2023) or Cosmogony 01 (2023)?

Watts: A place where we can meditate and learn.

Rail: It appears even more prominently in The secret house (2023). These symbols are found in Africa and yet we find ourselves in Russia-Ukraine in the North East with the house. What is it that was influential for you in Malevich?

Watts: It’s the universal. Malevich, Mondrian, Twombly, they all talk about universality. This is why I like those artists because they’re not artists saying “me!, me!, me!” It is the universe and universality that interests me. To create something new. The human being is first, and then you do what you like, but you have to understand that we are all human beings first.

Rail: And the universal is also understood through the language of mathematics as it is related to other painted images in each painting.

Watts: That’s right. Yes. Numbers, fractals. When you travel through Africa, you see fractals everywhere. The houses, I have seen how they’re built, how everything is made. It’s the fractals, it’s the cycle of repetition passing on from one generation to the next. And that’s also why I love Andy Warhol’s work, it’s about the repetition.

As for the use of numbers, for me, one can understand the world through mathematics, which is another universal language. Sometimes I use numbers and sometimes they stand in for a code. For instance, instead of A,B,C,D, I will use 1, 2, 3, 4, 5… Other people can then decipher them, but it won’t be up to me to tell them…

For instance, we could start by creating less weapons. The more knowledge there is, the more bombs are created. Mathematics is an alchemy, for it’s the infinite. So the more we do less, the less we will kill each other. For me, that’s what it means. Numbers serve to measure and differentiate quantities. You can understand medicine and science. It’s impossible to not have numbers around you. It allows us to build, to destroy, to comprehend, and do many things.

Rail: You pointed out how the number seven is significant in your work, and it also carries meaning in many cultures including Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and Hinduism, in particular.

Watts: Absolutely. In all of those cultures they know very well what seven means to them, be it a symbol of perfection, and eternal life, or wisdom, truth, etc., whereas for me, it means creation. I don’t know why, I couldn’t tell you, as it comes from so far away.

Rail: Which at times we can see it in recognizable forms of a foot or an eye…

Watts: Exactly. I’m playing with it, as I don’t want it to just be a number. I’d like to take these numbers and then modify them and bring other characters into the mix, like the @ sign. I don’t want to put too much emphasis on the study of numbers within my work because it’s not just about numbers, it’s really about painting. It’s the mystery of painting I’m interested in. I use numbers so there is a more expanded understanding about my work, but my work is not intended to be understood through numbers. In other words, the use of numbers is equivalent to the use of color or painterly gesture, as I’m expressing them visually. I’ve always said that once I’ve done my painting, it’s for everybody such that it doesn’t matter whether they like it or not, but at least if they’re compelled by it for a few minutes, they may ask questions about things.

Rail: I asked myself a question especially in front of the painting La Porteuse de Connaissances where we recognize the profile of a woman perhaps with a crown or a headdress in which there are numbers and characters inscribed.

Watts: Woman, symbolically in almost all the world cultures, represents knowledge. A woman has an energy inherent to her that is completely absent in men. I mean the energy of creativity. She has the energy. She is intelligent. She is the guardian of the cosmos, of our universe. There are symbols in numbers, letters, words, and so on that is associated with her as the bearer.

Rail: Numbers are so tied to their value attribution that we cannot easily dissociate those values from the symbol. They have cultural and historical meaning as well, and I see there is an evolution in the numbers you use, much like in history where we have Arab numbers and Greek characters used in math, which are much older than binary computer code. So there are new characters or numbers you notice and include in your work.

Watts: Yes, I am contemporary, from my era. It’s me.

Rail: We are connected to our time period by the @ symbol, which is prevalent today and ties us to electronic correspondence everywhere in the world. We are all connected through this mode of communication on Earth, perhaps even the cosmos.

Watts: It’s a continuity from work started in the 1980s–90s until the present day. We are sometimes a witness of time.

Rail: Are you searching for new symbols to include? Like hashtags, for instance?

Watts: I’m open to it, so it will come and I’ll borrow them. If you find something good, you can bring it to me! [Laughter] I’m trying to be as open and receptive as I can be. My work is a result or a product of that nature. In fact, for ten years, my work wasn’t shown, and I also didn’t want to show my work with just anybody, which is why I participated in group shows or people would come and purchase directly from my studio. I don’t run after financial success; my work comes first. There needs to be a symbiosis with the people I would work with so I would wait for those moments when I encounter an artisan, a dealer, a collector, museum director, an art critic… What is important to me is this humane relationship with an individual.

Rail: Which brings me to my next question on humane relationships. Could you describe your first encounter with Jean-Michel in Paris in January 1988 and his encounter with your work, when he came to your studio thereafter?

Watts: It was at the tail end of having worked all summer and fall of 1987 during which a friend had lent me his large studio for me to work in while he was away. I really wanted to seize this opportunity to make many big paintings and worked all summer. I had more than a dozen paintings, and I was ready by the time I met Jean-Michel. The first thing I noticed was he never forgot where he came from, even though he was born in the United States. He had a strong cultural memory. So when he saw my work, he more or less said it himself—he was looking to do the same. When Jean-Michel saw my work, he immediately loved it and started jumping all over the place. I was working a lot with materials at that time, working on floating drop cloths, I retrieved objects, and worked with things that didn’t have much value. But also the subjects I was treating were of images of African origin, as well as from ancient Greece and their relationship through Egypt in Africa. I believe he appreciated all of these things in my work together, and then two weeks after he got back to New York from his trip, his gallerist calls me to say that I should come to New York and show some of my work alongside Jean-Michel’s next show that year.

Rail: What were your impressions when you first arrived to New York for the tail-end of Neo-Expressionism? Who responded to your work and who did you meet?

Watts: People were very curious! The first person who came to see me was Rene Ricard, one of the most respected critics of the time. Jean called him and he came right away. Everyone wanted to see who this artist was he had met in Paris. He spoke French perfectly, so for me it was incredible, and we started having a conversation right away. Keith Haring also, I had been following his work for years since he had exhibited in Paris. I heard about what was going on with American artists beforehand and had seen some of their works exhibited in Paris. So, to come to New York and meet all these artists, art critics, and poets, it was fantastic. At the same time, I came towards the end of Neo-Expressionism, and also near the end of the AIDS epidemic, so Andy Warhol had just died a year before in 1987, but I did meet other artists like Francesco Clemente, Julian Schnabel, among others.

It was exciting as a community, for in Paris there were no Black artists shown in the big galleries. Really, there were none. I had been living in Paris for twelve years, so I was completely embedded in the arts community, knew all the museums, galleries, and people, and had friends, colleagues paying studio visits… like Nicolas Bourriaud, Gaya Goldcymer, Gérard Barrière, Andrée Putman, and Claude Picasso. There were people at the time already interested in my work critically, but commercially there were no prospects whatsoever.

On the contrary, New York has always been good for me, since my very first day here. Again, for me the most important thing was always the work and to show that I have made important contributions, strong, and solid, and I’m thinking about history, past, present, and future all at once. My first exhibition in New York was mostly bought by one Japanese dealer (Akira Ikeda), and in Italy I’ve had great experiences showing my work since 1999 at Magazzino Gallery where nobody knows me. I love the arts community and all my painter friends in New York. I feel like a New Yorker and an American, since becoming a citizen.

Rail: You’re from the Ivory Coast and you’ve traveled everywhere, yet we all carry our childhood experiences with us and our place of origin wherever we go. Since becoming an American citizen, do you feel more American?

Watts: America is built on immigration. Each person views America as they want. When I came to America, I knew its history before coming here. I’ve immigrated to the United States much like many people who came from Europe and Asia to this new continent, so I believe that I’m no different from that group of people. I came here to build.

We are here to build and not to deconstruct in construction. For me that’s very important. This is why we have a significant affinity with artists like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Philip Guston, Joan Mitchell, etc. all these grand artists and my good friend Brice Marden, who passed away recently. Come here and you can see what I painted in bold black paint on the I-beam in my studio ceiling: CITIZEN OF THE WORLD.