September 3, 2024

Download as PDF

View on Artforum

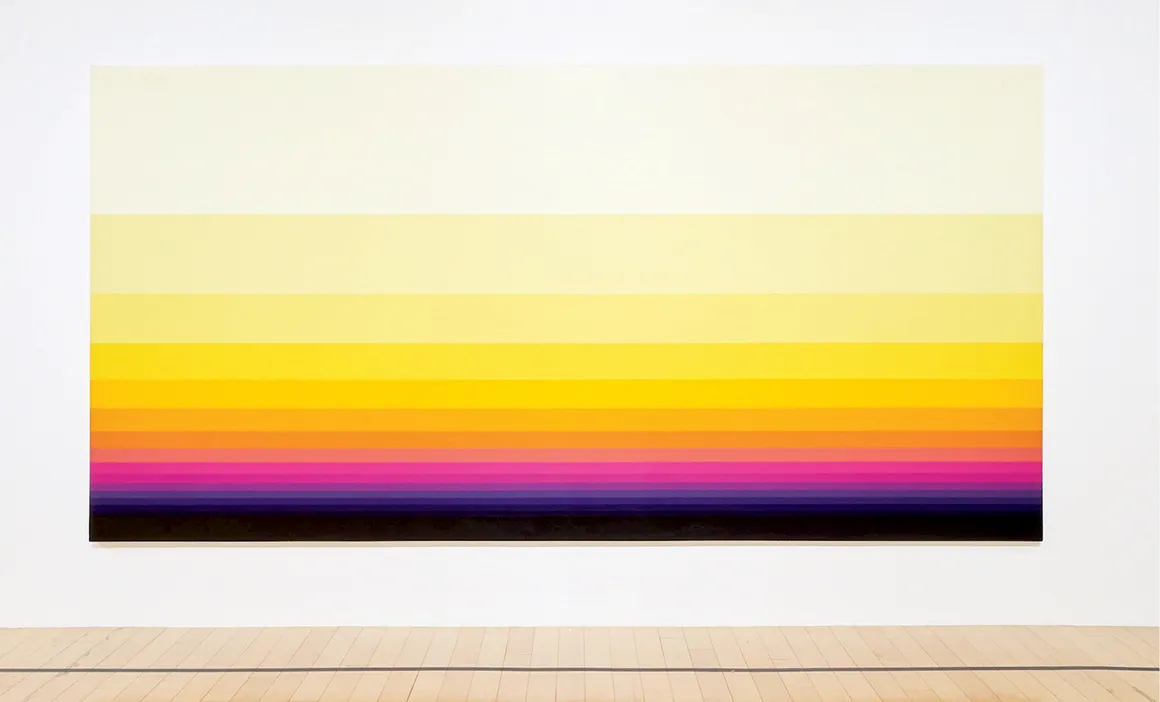

Norman Zammitt’s retrospective at the Palm Springs Art Museum begins with a version of an establishing shot: Visitors are sandwiched between two golden walls, their vision narrowed toward One, 1973, a monumental, stuttering painted horizon that effectively introduces the artist’s signature Gradations. Following a recent show at Karma—Zammitt’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles in more than a decade—this larger presentation, deftly curated by Sharrissa Iqbal, makes a case for the artist’s significance, and not only regarding the frequently remarked adjacency of his work to the Light and Space cohort. Zammitt (1931–2007) reemerges here as a phenomenologist set on describing relations and values, and how one apprehends them. Tall rodlike sculptures from the 1960s lean somewhat precariously against a wall, while nearby their denser, smaller brethren occupy pedestals like giant oracular paperweights. The latter, in particular, are acrylic prisms, which the artist made by sandwiching or congealing painted translucent sheets, which he sometimes offset. The label for Caugnawaga II, 1966, a plastic block of trailing psychedelic colors, notes how the artist “invented a kind of pigment that could withstand the liquid acrylic glue used in the laminating process.” And, indeed, Zammitt as engineer is a throughline in the exhibition, suggesting in its chronology a developmental logic of experimentation within shifting materials and tools.

The inclusion of these early sculptures facilitates such a reading, as their superimposed layers foreshadowed the logic of the Band Paintings that followed for some twenty years. As did One, these works further Zammitt’s approach to material tiers—now pigment in an acrylic medium—set in close proximity, the better to conjure depth. (The stratified lines of color might invoke the sedimentation of geological deposits, except that the indication is so insistently sky, given the weight of their hues observed in its endless permutations.) Green One and Arctic Yellow, both 1975, are hung within eyesight of One, which serves as a historical precedent for the related paintings and a baseline from which to glean how Zammitt tries out different color combinations: nocturnes to rainbows, some fiery neon, others muted sherbet pastels. Some are massive, and many are more diminutive, less than a foot wide, but each is an instantiation of a willfully dissimilar temperature and mood. As a group they variously feature thicker or thinner bands, as well as increasingly subtle gradations. In keeping structurally consistent with his 1960s sculptures, Zammitt continued to work with novel technologies (a point of connection with the upcoming 2024 theme of the Getty’s PST ART: “Art & Science Collide”)—in the case of the Band Paintings, relying on calculations generated by an Atari 800 computer program that he developed with scholars from Pasadena’s California Institute of Technology.

These clean and bright abstractions come close to the appearance of hard-edge LA abstraction (e.g., that of Frederick Hammersley, who also made computer drawings in the 1970s), even as they admit the impossibility of the autonomy from referent that critic Jules Langsner originally described in the work of Zammitt’s Southland predecessors. Yet beyond the coruscating light so specific to Los Angeles, the predominantly near-but-not black, yellow, and orange North Wall, 1976, introduces the apposition but not the appropriation of Mexican serapes and Indigenous textiles. As a child, Zammitt lived on the Kahnawá:ke Mohawk Territory near Montreal before moving to California: This point of origin is referenced in the altered spelling of the reserve’s name in Caugnawaga II. The works are consistently grounded, bands terminating in—or ascending from—the pictorial floor extending across the panels’ lower edges. Yet from the 1980s on, Zammitt focused on what hovers above them, forgoing their gradual changes for an exploration of an untethered and seemingly perpetually reorganizing space caught in some determined if arbitrary moment. In these “fractal” paintings, derived from his study of patterns emergent from the mathematics of chaos theory, outlines of shapes hover before and merge with their environment. These are images of mutual penetration and, in the context of the show, stand in for the more literal self-portraits that the artist made in his last years, which are bracketed out. What remains are the representations of environments and reciprocal becoming.