October 1, 2024

Download as PDF

View on Artforum

I tend to think of Photorealism as an -ism like any other. It had its moment (the late 1960s), its question (how to paint after Pop), and its heroes (e.g., Chuck Close). Against this assumption, Dike Blair treats it as something closer to a medium, so that, in principle, there could be as many types of Photorealism as there are photographic styles. Inspired by Edward Hopper’s 1939 canvas New York Movie, this exhibition, titled “Matinee,” solicits obvious comparisons with cinematography. The show asks, What would it mean for a painting to capture the specific mood and syntax of a film?

“Matinee” takes place at the Edward Hopper House Museum & Study Center, located in the riverfront town of Nyack in New York’s picturesque Hudson Valley. The building’s facade boasts wisteria vines and a prominent bay window, exuding Americana. Inside, decorative moldings and wide-plank wooden floors implicitly rebut the nondescript sparseness of urban gallery spaces, as though claiming that this setting best complements Blair’s work, which probes the relations between domestic and psychological interiority.

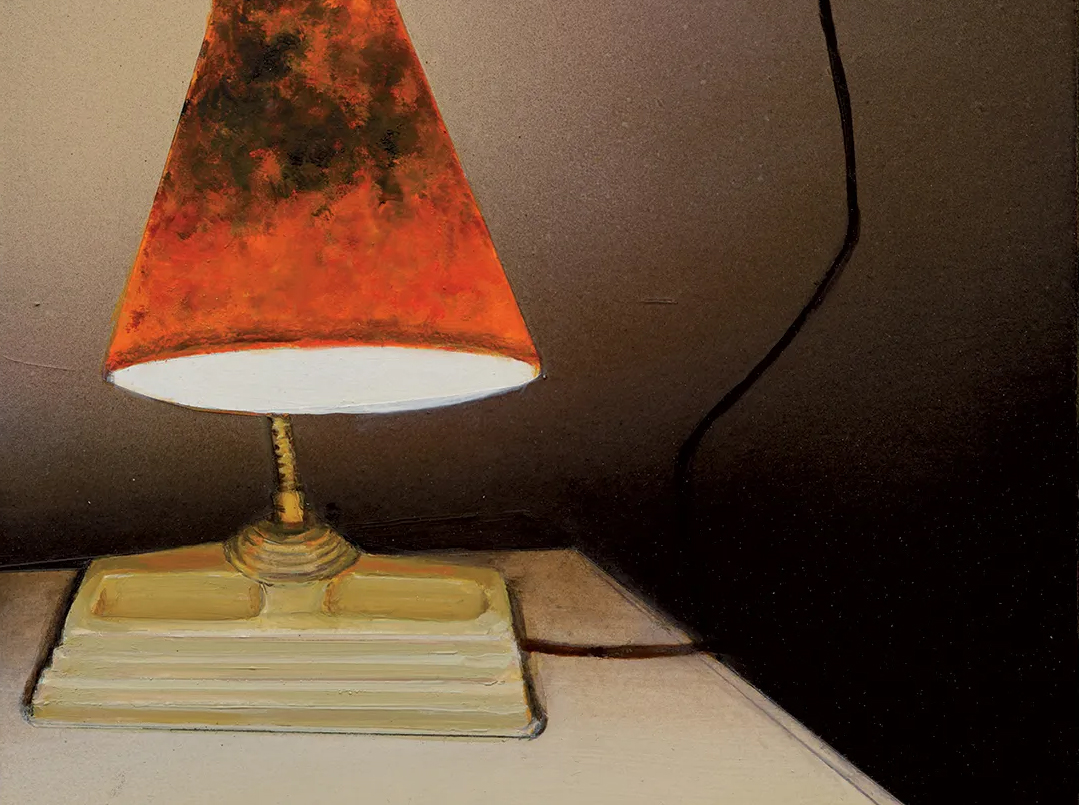

Exploring this theme, the mostly untitled paintings are divided into roughly three moods, each evoking a cinematic genre and its characteristic mode of artificial lighting. A trio of works seem to epitomize these categories. In one from 2009, the white lines of a parking lot phosphoresce before unseen headlights, summoning the eerie asphalt of neo-noirs like David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (2001). In another from 2007,a sad-looking microwave glows under cheap fluorescents, recalling the depressing kitchens in dark comedies such as Jill Sprecher’s Clockwatchers (1997). And in a 2021 canvas, a red-shaded lamp castsits golden halo on a bedroom wall, conjuring the incandescent moodiness of thrillers like Paul Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct (1992). This last genre appears to be Blair’s favorite. It lends itself to a forensic sensibility, which animates his compositions of isolated objects, seen in shallow focus at close distances.

Apart from this milieu, Blair also invokes cinema in his preferred viewpoints. A lamp, a microwave, and an electrical cord are all things we look down on. We encounter them at steep angles, our chins moving toward our chests. Portraying these objects from this tilted position, the artist emulates a conventional unit of cinematic editing, the point-of-view shot. Here again, however, Blair maintains a frictional difference between media. While any frame could, in principle, be from a POV shot, most require the syntax of montage––e.g., first a picture of a hungry face, then one of soup, and finally one of hands reaching for a spoon. In a single painting, however, this context is not possible without some shorthand convention for first-person perception: here, the canted viewpoint.

Crucially, these tactics do not one-sidedly surrender painting to cinematography. Unlike the brushwork of canonical Photorealism, which is slick and seamless, Blair’s can be blunt and textured. More slyly, he defends his medium in witty moments of self-reference. For example, when he portrays a cord on a garage floor, he renders the concrete surface—splattered with multicolored flecks of paint and marked by the diffuse spray of aerosolized pigment. Likewise, in another image, the cord abuts a traffic-cone orange bucket. As a depicted object, the container alludes to the packaging of store-bought house paint. As a depictive surface, it serves as a metonym for color as such via its saturated hue. The same goes for the lime-painted wall in another untitled 2016 work, which both depicts and bears its lurid tone. Or, finally, the white lines of parking spaces which are, after all, painted on the ground. Thus, while Blair emulates film photography’s mise-en-scène, he refuses to let it subsume his medium. Instead, he recursively reinscribes painting into his otherwise cinephilic images.