October 1, 2024

California may contain all the majesty of heaven on earth, but you’ll mostly see it at 65 miles per hour. Framed through a car window, the shudderingly beautiful landscape can seem as far away as paradise, while every destination feels discrete, as though it exists in its own private compartment of space and time. The promised land at the far end of the vast American desert was a real place, not a mythical one, and in less than a century’s time it was paved over with concrete.

“At the worn-out end of the 20th century, much of our degraded American environments project the sadness of lost glory or the sadness of careless design,” the painter Jane Dickson once said. Exhibited in Are We There Yet? at Karma Gallery’s West Hollywood location, Dickson’s paintings of Southern California streets are undoubtedly landscapes, even if they contain few hallmarks of the genre. Greenery, including the region’s iconic palm trees, is often mere suggestion, while epic sunsets seem to shrivel and wilt under the single-point perspective, as if sucked into the vacuum of the road’s horizon.

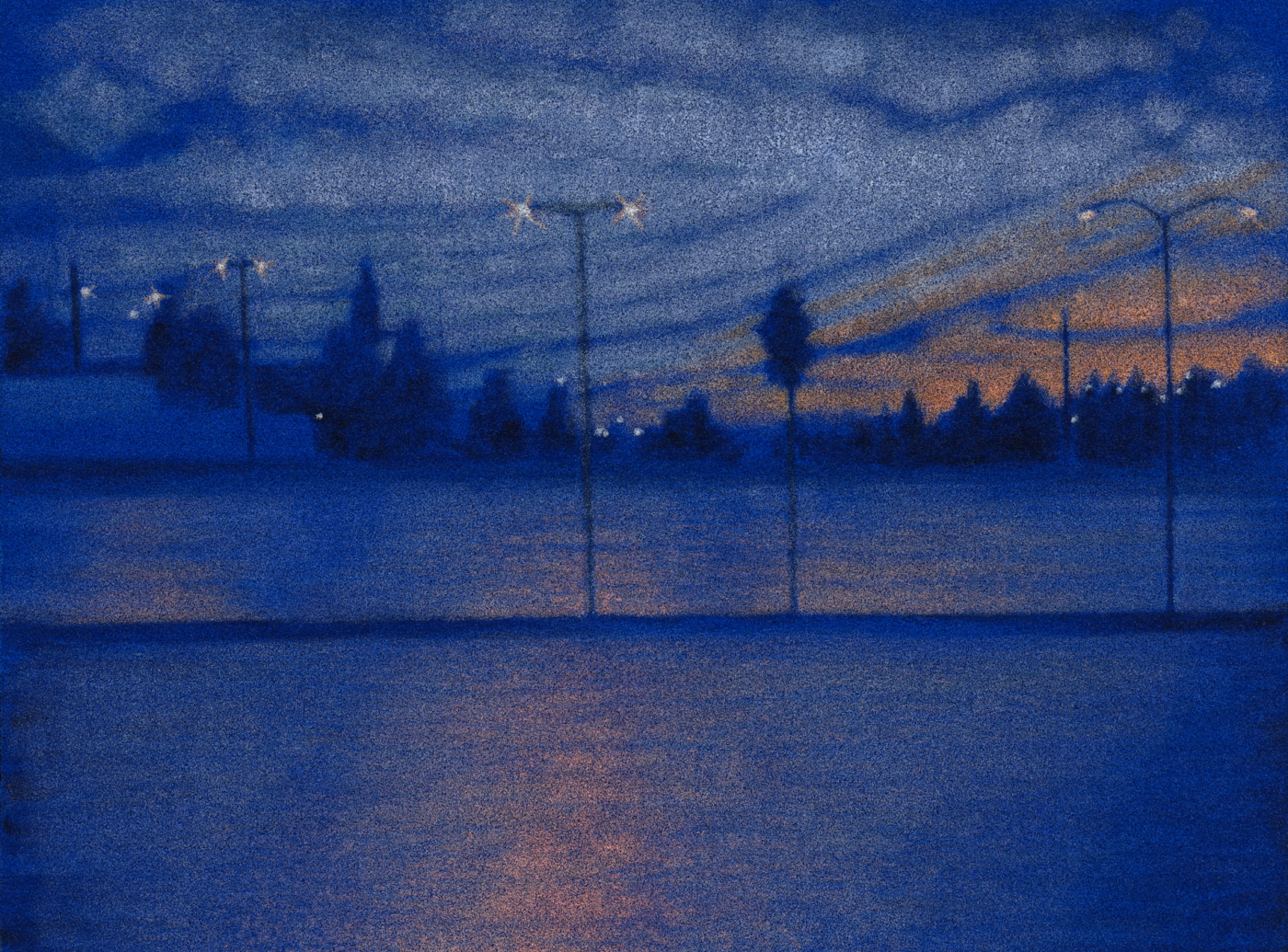

Dickson works in crepuscular scenes, dawns and dusks described in carefully controlled palettes. Moody yet humming with life, they capture Hopper-esque visions of low concrete buildings and highways cutting through California terrain. North State Rainy Parking Lot (2024) depicts an empty car park, streetlights shining like shards of glass above a glistening plane of asphalt. In Red Tail Lights (2000), half a dozen cars glow under a cerulean sky, while a heavy wave of clouds threatens rain. Despite their disquieting anonymity, the paintings are imbued with a powerful sense of place, sharpened by Dickson’s attention to regional detail—the blue-and-yellow advertising balloon floating beside palm trees in Smog Check (2024), or the stuffed animal perched in the rear windshield of a well-maintained pink vintage car in Big Dodge (2024). You could draw a straight line through these works connecting Ed Ruscha’s coolly ironic icons of the American West to Cynthia Talmadge’s Pointillist paintings exploring the banality of bliss.

Throughout Dickson’s body of work—particularly in her seedy vignettes of Las Vegas casinos and sex workers around Times Square—American cities are essentially virtual environments, dark fantasias of roiling, sublimated desire. Here, billboards, traffic lights, power lines, and street signs frame the headlights and taillights of cars like distended shadows. Dickson’s vehicles offer none of the Ballardian eroticism of John Chamberlain’s sculptural junkers. Nor are there drivers or pedestrians in her California paintings. Cars, in Dickson’s work, rove herdlike across public land; they reconfigure space, creating the illusion of autonomy along preordained roads and a feeling of calculated access to the natural world. As she told the painter Odili Donald Odita, “These are my transcendentalist works, the sublime in traffic.”

That is to say, Dickson’s paintings are about the American dream. They inhabit the same parallel routes of self-actualization and Manifest Destiny that structure a Robert Frank or Jack Kerouac road trip. But there’s less optimism here. Out of Here North 3 (2013) shows a caravan of cars stuck in traffic beneath ominous power lines, the fiery orange sky tinged by aquatic green clouds. In otherworldly cool tones, the paintings suggest the twilight of empire. Rendered in oil on rectangular plots of AstroTurf, they summon golf courses, soccer practice, manicured lawns. The shadows between the artificial blades of grass lend a hyper-clarity that dissolves, as you approach the painting, into a bristly static energy. The image is only possible to apprehend at a distance.

In a side gallery are fifteen oil-stick-on-linen works depicting US highways from Dickson’s “Road Trip” series. They’re painted, like all of her work, from photographs taken by the artist, and their vantage is through a windshield, slightly left of the road’s center—probably a view from the driver’s seat. Their trancelike monotony will feel familiar to anyone who’s undertaken the Great American Road Trip—you can almost hear the hum of rubber on tarmac, or the ebb and flow of radio static that fades region into region. Yet there are no grand vistas, no awe-inspiring mountain ranges or desert sprawl—just long gray stretches of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Interstate Highway System, navigated by anonymous travelers whose lonely journeys are punctuated only by the idea of beauty.