Autumn / Winter 2024

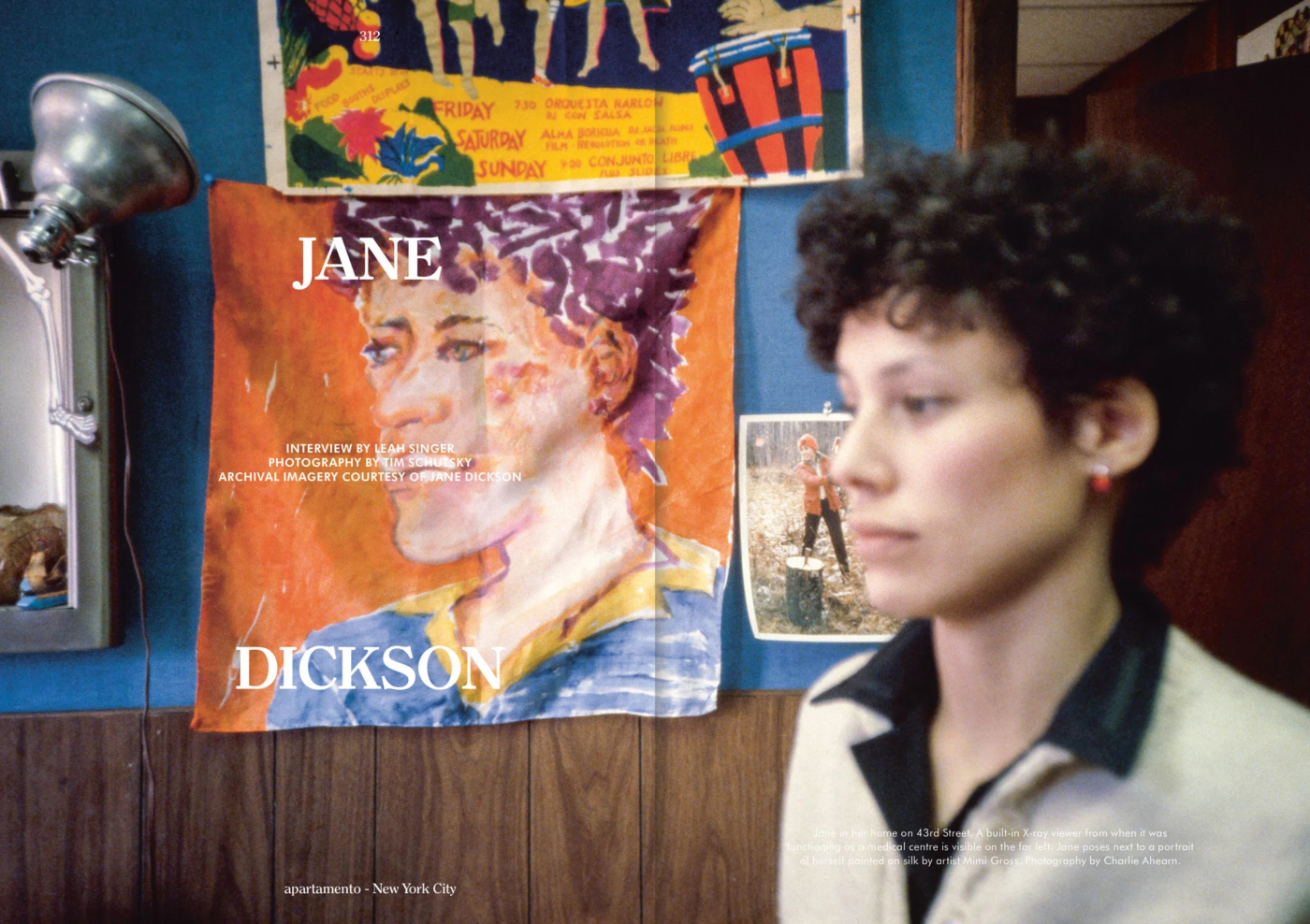

When the painter Jane Dickson and her husband, the film maker Charlie Ahearn, lived in New York’s Times Square in the ’80s, their apartment was like a tourist attraction for out-of-town friends. Jane knew it was an odd place to live, especially at that time when a level of lawlessness and neglect ruled the area, but it became fertile ground for her burgeoning forays into artmaking. Her enduring connection to Times Square began in 1978 when she got a job creating the computer generated animations for the Spectacolor sign, the district’s first electronic billboard. Attached to the New York Times Building, the sign sat beneath the iconic Times Square Bail. She ran the countdown to midnight a few times, flashing the numbers across the screen. Three decades later, she created 70 life-size mosaics, called The Revelers, for the Times Square-42nd Street subway station. They depict the range of people who gather in the streets each New Year’s Eve to celebrate and watch the ball drop, and Jane and Charlie are known to still celebrate in their old hood. But there is much more to Jane Dickson than her noted association with New York’s everchanging Times Square. With a deep interest in exploring serial themes, she is equally recognised for her paintings of demolition derbies, Las Vegas casinos, suburban houses, bridges, highways, and street signage all done with a curious but suspicious eye, reminding us of the potential danger that lurks beneath the sanguine surface. A move to Brooklyn, after years of living in Tribeca, post Times Square, finds the artist couple living with their grown daughter, son in law, and granddaughter. I’ve known Jane and Charlie for years, partly from their former lower Manhattan neighbourhood but also from the downtown art scene where they hold a distinctive place of honour. During my visit, the studio was getting ready to ship out work for her first show in Los Angeles with Karma gallery. Titled Are We There Yet?, the show will feature paintings of the highway seen from the front seat of a car; most are depictions of LA. Even as she captures the scenery outside the window advancing towards the horizon, we know that Jane is still peeking in the rearview mirror.

You have a studio building in your backyard!

As a mom and a spouse, you know that when you’re at home, people run in all the time: ‘We’re out of toilet paper’, ‘Can you show me how to unlock my phone?’ The biggest challenge during the pandemic was making boundaries. I’d drift into the kitchen for a cup of coffee, but my head was still in my studio. I didn’t want to switch gears by having to talk to someone. Even in my first studios, I would get into this dream state and forget that I was hungry. I’m still that way.

During the pandemic, you hadn’t moved to Bushwick yet.

We wanted to move, but we couldn’t sell our Tribeca place during the pandemic because no one was looking. People thought no one would live in cities again. As the pandemic waned, my professional life changed. I knew I was going to be in the upcoming Whitney Biennial because they came to my studio the week before the pandemic. Then it was postponed a year, so I had a lot of uninterrupted time to work. The Biennial generated renewed interest in my paintings. I realised it was now or never-this was when I needed a bigger studio and if I gave myself the space, a lot of great things could happen. It was a leap of faith.

At what point did you decide this was going to be a multi-generational family house?

I always fantasised about having a little grandchild who could toddle up the stairs to visit Grandma and Grandpa. Rita was born during the pandemic. Eve and Robert started looking to move because they were in a one bedroom and worked from home it wasn’t sustainable. I thought, ‘Wait a minute, what if we look for a big place together?’ When I found out that the studio listing I saw came with a house, I went, ‘Oh my God, it’s got a two family house. This is the perfect place for us’. They were sceptical at first, so was Charlie, but I was ready to jump in.

How long has it been, and how is it going?

A year and a half. From my vantage point, it’s fantastic. I think from Charlie’s, it’s also great. As you get older, your children tolerate you with various levels of enthusiasm, but I would say they’re happy here.

Moving to Bushwick with your extended family and starting anew was a pioneering decision. You’ve always been a trailblazer you moved to Times Square in 1980 and started your family there.

I always wanted to be an artist, and I always wanted to be a mom. We moved from Times Square to Tribeca in October ’92 when Joe was six and Eve was three. We were trying to leave Times Square as soon as Joe was born, but we couldn’t manage to find a place to move to until there was a downturn in the real estate market.

You moved to New York in 1977 at a heavy time-the city was suffering from financial ruin, electrical blackouts, the Son of Sam serial killer on the loose, and lots of street-level crime. A year later, you landed a job working on the Spectacolor billboard in the epicentre of the city.

I started working on the first digital light board in Times Square as an animation designer on the weekend night shift.

What were the circumstances that led you to eventually move to Times Square?

In 1979, I moved into Charlie’s loft on Fulton Street. Cindy Sherman was our nextdoor neighbour. It was an office building that artists were camping out in there was no plumbing in any of the apartments. Cindy did all her early film stills in the hallway. In 1980, Charlie started working on his film Wild Style. The film crew was there all the time, so it became untenable. One day, Charlie came to pick me up at work and suggested we move to Times Square. I told him there were lofts for rent at 276 West 43rd Street. Half the building was empty, and the block was condemned. They were just waiting until the city paid them to tear it down. The loft was long and skinny and had two solid walls of windows. I had a studio at one end, but the film crew would come over all the time, and there was a lot of energy and excitement. I’d get distracted, ‘Oh, Jean-Michel Basquiat is here. I’m going to say hi’. I ended up getting a studio around the corner on the Deuce, 42nd Street.

What was that like?

It was really skanky. The building was being warehoused, so the landlord was renting out these small offices. My space had been a blood bank, but it closed because of AIDS. Meanwhile, the super was renting out the lobby to drug dealers.

When did you first start thinking you would have a family?

I had a ruptured ovarian cyst in ’83 when Charlie was taking Wild Style to Cannes. I remember going into the emergency room and telling the doctor, ‘Wait, I have to go to Cannes tomorrow’, and he was like, ‘You’re not going anywhere’. When Charlie called me, we had been together for four years by then, he asked what he could do, and I said, ‘Marry me!’ When he came home, we got married. Joe was born in 1986.

Were you still working at Spectacolor?

I quit in ’83. Spectacolor offered me a job as an art director, but I didn’t take it. I was happy to learn about computers there were no schools teaching computer art yet. I thought it would be a useful skill because computers were becoming a thing. But once I did it for a while, I thought, ‘It has no smell. It has no feeling, it’s not tactile’. What I love about paint is the way it smells, the way it feels, and the way you can mush things together. I always wanted to reach into the monitor and smudge something, and you can’t do that. My colleagues were going out to LA to start a special effects company, and they wanted me to come with them. I had professional opportunities to be on the cutting edge of computers or be a retro painter; I chose painting. I had my first show at Patti Astor and Bill Stelling’s Fun Gallery in the East Village.

You imagined Times Square as a canvas for yourself and other artists. With the arts collective, Collaborative Projects Inc., you were an integral part of the culture busting monthlong The Times Square Show in 1980 when artists took over a former massage parlour to exhibit their work 24/7. You also convinced your boss at Spectacolor to use the sign as a vehicle for artists.

I gravitated to Colab and another artists’ group called Group Material because I was interested in collective effort. My belief has always been that art is most interesting when it’s a dialogue and not a chorus of monologues, which I think is often nurtured in art school. I like interacting with people. I also have always been interested in spotting opportunities.

You saw the potential of the Spectacolor sign.

As soon as I started working, I thought, ‘What more could I do with this besides ads for Coca-Cola?’ We had an obligation to do public service messages between the ads. Early on, I told my boss I could do art ads because I had experience working with the animator Suzan Pitt. Her film, Asparagus, premiered at The Whitney Museum, and she made an installation around it. I asked if I could do an ad for the exhibit, and later, I did one for The Times Square Show.

After you did the art ads, you hit on an idea called Messages to the Public which featured works from a series of artists. Could you tell us about some of them?

After doing the art ads, Spectacolor was willing to do art projects. I had gone with the painter Walter Robinson to talk to Jenny Dixon at the Public Art Fund about raising money for The Times Square Show. The timing was too late, but she was very interested in funding something for the Spectacolor sign. I became friends with Keith Haring, who was still a student, and it got me thinking about all the artists I met through The Times Square Show who were making good work, not just the ones who were my favourite artists or my best friends. I think a lot of people stick with their best friends forever and pat each other on the back. You don’t grow that way. I was interested in people that I didn’t know who could challenge me. Jenny Holzer was doing Truisms already, but they were on paper cups and xeroxes, so I introduced her to LED lights. Keith Haring was a no brainer, he was doing these very simple figures, and our sign was a very crude set of light bulbs with four colours and clunky animation. I also picked David Hammons in that first year, and Crash, the graffiti artist, did a beautiful piece. I invited Nancy Spero and Barbara Kruger who proposed pieces on the right to choose, but it turned out my boss was a staunch Catholic, and he vetoed both of their projects.

The series continued in different forms after you left Spectacolor.

It was eventually taken over by Creative Time, and it moved to a real video screen, and now it’s called the Midnight Moment. It really is a project that has run since 1983.

Did you come from a creative family?

My mother was creatively ambitious but frustrated. She was a ’50s housewife who aspired to be a writer, but life and her own inhibitions got in the way. When I moved into this place, I felt like I moved into my mother’s dream home because she was really into antiques. She spent so much time in each place she lived, fixing up her study where she was going to write, but she would get really obsessed with decorating and never finish anything she wrote. I think I’m established enough that I can do this house and not have it eat me. I have to be really careful that I’m not thinking too much about what kind of carpet we’re going to get. Part of living in Times Square was to get as far away from my mother’s obsessive domestication as I could. Our loft in Times Square had been some kind of a medical clinic. There was a bunch of little cubicles with one of those sinks you’d turn off with your elbow, and it had a thing to look at your X-rays. It was impossible to domesticate it. We had a hot plate and an under-the-cabinet mini fridge. It was bare bones. I’m trying as a householder to chart some middle path. I inherited my mother’s stuff, no one else wanted it. I put it all around, and now I feel like I’ve decorated the house with my mother’s knickknacks.

You’ve said that after The Times Square Show you felt an urge to paint subjects you knew well. This was the moment you recognised that Times Square was going to be your subject matter and that photography would help you to later conceptualise it in paint.

I dated the filmmaker Peter Hutton my first year in New York, and we would go see films by Dziga Vertov at Anthology. He used to carry around this small Minox camera, and I wanted one too because I was ecstatic about being in New York City. I remember as a kid looking out the window of the car at night when we’d be coming home from my grandparents’ place in Chicago and thinking, ‘If I could just capture that, people would understand how I feel’. I was also friends with Alex Webb, a Magnum photographer who invited me over one night to see some photographs he took for a magazine cover. I was astonished to see he took 600 photos of the same thing. I thought photographers magically got the perfect frame. I learnt that’s not true. Photographers take a million pictures, and in those million you find the one where the heavens parted, and the chorus began to sing, and it’s perfect.

Your paintings are so cinematic. They are reminiscent of film stills captured action shots or static shots where something just happened or is about to happen. There is also a great deal of attention given to perspective-low angles, high angles-it gives you a thrilling feeling of anticipation as you would get in cinema.

I studied Japanese ukiyo-e prints and Chinese scroll painting. I wanted to do streetscapes from above, and Western landscapes are always horizontal. My compositional choice was a very conscious art historical reference. I also inhaled the films of Dziga Vertov. And growing up in the ’50s and ’60s, I watched tonnes of film noir on TV. I remember someone asking me early on, ‘What is the source of your art?’, and I said, ‘Fear’. For the Times Square work, that is absolutely true. Other series, like the house pictures I painted on carpet, were done when I was a new mom, and I was trying to figure out what home looked like. It seems crazy now, but I had two kids growing up in Times Square, so I started painting houses. I was trying to visualise what home I could make for my kids after we moved. I would use my art, often unconsciously, to deal with things I was conflicted about, afraid of, or confused by.

How did photography help you in the process of making paintings?

The Pictures Generation artists talked a lot about the camera and its role in painting. I’m

interested in using the camera as a reference, so it helps me remember what I think I saw and what I felt. Sometimes, my photo will not be of the actual drama. It’s more like, ‘This is what the corner looked like after that scuffle that I didn’t have my camera out for’. In my early work, I would get people to pose for me, usually Charlie. They’re reenactments a lot of the time. Once in a blue moon, I’ve used someone else’s photo, often Charlie’s, because I think, well, he caught it, but I was there with him.

You don’t use found photographs as source material?

I almost never open the newspaper and go, ‘Oh, I’ll make a painting from that photo of this place I’ve never been to and don’t know anything about’. By keeping it to my photos, it means it’s things I’ve actually experienced. I’m not a great photographer. I took a photo class once, and my favourite part was watching the black-and-white photos develop. When I started to paint on dark grounds, it mimicked that process. This painting over here is in progress, it will develop, and the whites will become brighter. Maybe the darks will become darker. It starts in a very narrow central band and becomes more extreme as I go along.

What about your materials? You choose unconventional surfaces to paint on such as carpet, AstroTurf, garbage bags, Tyvek, sandpaper, and felt.

I like materials that really resist being painted on. I love that challenge of ‘How am I going to get this to work?’ I bounce between materials because I feel like once I get a good facility, it’s time to mix it up; the challenge is really important. I don’t want it to be easy. Then I don’t trust it. I’m not comfortable with comfort.

It’s like your Times Square loft and its resistance to decoration.

Exactly.

I like the strippers on sandpaper series you did in the early ’90s where the desirable is presented on this rough material as if inferring ‘stay away’. There is an implied connection between the material you choose and the subject matter. The oil stick on sandpaper even looks like the pointillistic pixels of the Spectacolor sign that first brought you to Times Square.

The early Times Square work was all oil stick. Before that, I just drew and did printmaking. The oil stick only came in six colours then. Having this extremely pareddown palette was a really helpful way to start painting. If I wanted purple, I had to mix the red and the blue. If you have too many colour choices and you don’t know what you’re doing, you just make big messes. Using the oil stick was really like drawing.

In 1980, you made a series of drawings called, Hey Honey Wanna Lift? based on the pickup lines guys used on you. The work came out of frustration, but you made it your own. All of the drawings feature exaggerated penises. They are like cousins to the penis paintings by the artists Lee Lozano and Judith Bernstein.

That would make a great show! I showed them with the Brooke Alexander Gallery. It was one of the first things I showed publicly. It terrified and confused men. They’d say, ‘Oh, you’re this angry women’s libber’, or, ‘Hey, I thought you’d be in thigh-high spiked-heeled boots and leather spandex. You just seem so normal. I thought you’d be this maneater’.

What was the overall reaction to the paintings coming out of your Times Square experience?

Before we left Times Square, I did the stripper paintings, and some people were like, ‘Tsk, tsk, you have little children and you’re doing naked people’. They’re not X-rated. They’re nudes, nudes stripping. There was a lot of pushback. Mothers are supposed to be absolutely asexual, and random people feel like it’s their job to censor. I felt like I was living in Times Square portraying the street, but the heart of Times Square was the sex trade, and I wondered if I could address that before I left.

Why did you return to the series, Hey Honey Wanna Lift? in 2016?

I did a summer show with them for Johan Kugelberg’s Boo-Hooray gallery in Montauk called Dicks and Garbage Bags. Then I showed them in a big installation at the SPRING/ BREAK Art Show in New York. I can’t exactly remember why I came back to Hey Honey Wanna Lift? except that we were working on my Times Square book, which forced me to go through all my work. I think like most artists, I want to imagine I’m a tabula rasa, that at any moment I can start fresh. But I realised that I’m not a kid just starting out, I do have a body of work. I looked at all of my history and started to think, ‘What do I wish I had done more with?’ It’s not cheating to return to previous themes. I’ve done it multiple times. At different points in your life, the same subject matter can change, you can change, the world changes, and my relationship to the subject changes.

Did the pandemic pause give you time to rediscover your large archive of photographs?

During the pandemic, my then assistant needed to work so Johan lent us a scanner and she scanned all these negatives. I would not have done this on my own. With Photoshop, you can take bad exposures and find new things in them. I found all these treasures. Back to the question of why I revisited Hey Honey Wanna a Lift? I guess I felt like it was an underexplored series.

Your friend, the photographer Nan Goldin, called you ‘The painter of American darkness’.

I experienced my childhood as pretty dark and scary. There were people that loved me and nurtured me, so it can’t have been as dark and scary as I remember it. My father had a serious drinking problem, and my mother had OCD. From early on, I was the designated little mom to my parents as well as to my siblings. My parents were really negligent and checked out. When I was four, my little brother almost drowned. I pulled him out. I think everyone was drinking. I was very watchful. You could say paranoid. I always think of my marriage to Charlie. He’d suggest lying in the grass and looking up at the stars. Whereas my reaction is, ‘I can’t lie down, there might be somebody coming. I hear a rustle in the bushes’. That’s really my nature, and I feel like my art is what keeps me sane. My parents were comfortably well off. The facade was very nice. But when I moved to Times Square, nobody’s pretending they are nice, they are upfront just creepy. I never thought people would accept this work. I thought, ‘I’ll do one show at Fun Gallery and see’. I really wanted to be an artist. I wanted to come to New York, and if it didn’t work out, I would do something else. I thought people would say, ‘Who would want something so depressing?’ But people keep letting me do it.

There could easily be an eponymous adjective to describe your work.

Dicksonian. The first time somebody said, ‘I looked down the street, and it looked just like one of your paintings’. I thought ‘Well, if you know what my paintings look like, then it’s time for me to change’. But now I think it’s OK, I can embrace it.