January 28, 2025

Download as PDF

View on Paper Magazine

Tabboo! Tabboo! Tabboo! With its original spelling and self-excited punctuation, the artist and drag legend’s name makes for its own glittering trademark. It’s name as announcement! Appellation as event! A florid-fun self-invention meant for top billing on a Broadway marquee! When scrawled in the painter’s hand, his signature gathers around itself before branching off into curlicue spirals, flowering across the canvas like an Art Nouveau fever dream. In his starring turn (as who else? himself!) in the cult documentary Wigstock, he was told to drop the exclamation point from his own credit in respect to the other girls. Fair enough. He stole the show anyway! Taking to the stage in a too-short mini-dress, while squawking out “It’s Natural!” over a rudimentary rap beat, you’d be forgiven for thinking that this was his defining moment; when “the Daffy Duck of Drag,” shone bright beside the likes of his world-conquering co-stars Candis Cayne, Lady Bunny, Leigh Bowery and a certain Supermodel of the World.

But Tabboo! has never stopped being a main attraction. For decades, the artist born Stephen Tashjian has helped shape the visual sensibility of everything from Deee-Lite to Drag Race, Marc Jacobs to Madonna. He is probably the only working painter who can confidently claim both RuPaul and Nan Goldin as his peers. Like them, Tabboo! honed his craft in the cross-currents of downtown nightlife, serving as an all-purpose creative; eternally game to paint a backdrop, design a costume, staple a flyer, model a collection, perform a reading or high-kick onstage. His glamour was messy, make-do and completely sure of itself, applying impasto blobs of mascara and rouge until his face resembled a Liz Taylor Halloween mask. If Candy Darling and her fully realized fantasy represents one tentpole of Queen-dom, Tabboo! was a star student of Jackie Curtis: rough and ready, with a burning commitment to his own imagination.

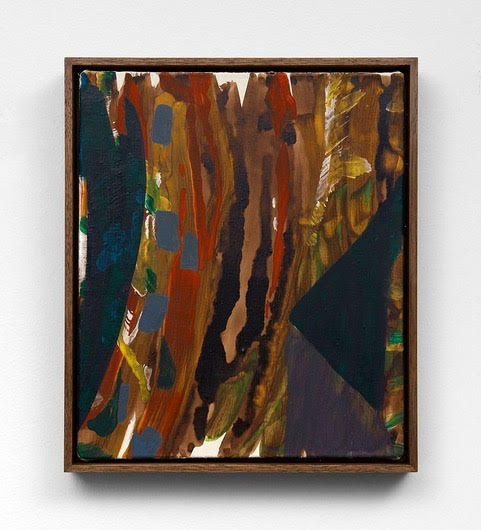

His latest show, Early Works at Karma and Gordon Robichaux, is a snapshot of the artist at play, corresponding to a period when he was gleefully pumping out work as the pace of New York Culture began to rapidly pick up speed. After making a small name for himself in a clique that included Jack Pierson, Mark Morrisroe and Goldin (later dubbed “The Boston School”), Tabboo! moved to New York in 1982 and immediately threw himself into nightlife. Most of the work on display is actually quite practical, whether that means announcing a club night or enticing you to try on hot pants. Hand-painted advertisements for Fiorucci, Williwear and “drag racing” at the Pyramid Club are jagged but punchy little collages, where the coherence of arms and legs gets chopped and screwed for proper formatting. Individual words are either singled out and manicured to perfection or detonated into graphic supernovas. For the latter, check out Jane is Sexy (1981) and Yes (1984), which look like someone stuck a stick of dynamite into a Charles Demuth painting. The artist’s loopy, spiralling calligraphy is the show’s great standout, and is as immediately recognizable and compelling a tag as anything Keith Haring ever did.

The work has the same vibrancy and lurid color scheme as Expressionist paintings but without the abjection or smell of death. Even in pieces that are exceptionally gnarly like Self-portrait in Drag as Popcorn (1983) or explicitly meant as tributes to the fallen like Ethyl Eichelberger, Freddie Mercury, and Jackie Curtis (all 2005), there’s a funny way that sorrow or angst is kept at bay. It’s counterintuitive that turning your life into a cartoon would give it a measure of depth but at his work’s best, Tabboo!’s unyielding cheer is an attitude that resists ever being diminished.

PAPER spoke to Tabboo! about JetBlue, Basquiat, Beyoncé, penmanship, puppets and much much more.

The first time I ever saw you was through watching Wigstock. And then the last time I saw you it was on an airplane because it was playing in-flight.

On JetBlue? Isn’t that wild? Over the Mid-Atlantic! That’s part of the woke agenda. They needed an LGBT film and they had three: Wigstock the Movie, To Wong Foo and Paris Is Burning.

The first time I saw Wigstock I really had to look for it and now it’s right there next to like, Inside Out or Paw Patrol. I was curious if you could talk about the trajectory of that movie.

When Wizard of Oz came out the same thing happened. It came, it showed a couple months, and then it disappeared for years and years and years. Then they started showing it on TV every Christmas. Now that movie has been seen more than any other movie ever.

I didn’t realize Hollywood would come downtown, but I knew the whole underground was bursting out. It was too big to be held underground. But in the middle of making it the producer died, so there was no push. The movie played in the small theater under the staircase at Film Forum or Angelika, so no one in New York even came. It kind of died in the woods. 10 years later, it showed in a midnight thing on Turner Classic Movies, so it’s out there as a gay movie to be seen. So we need a movie, we need an LGBT movie and they went with that. I have pictures of me sitting on the plane up in the air over the Atlantic, and I’m on the screen as a movie star for everyone to see.

What I really like about the show is that a lot of these pieces are practical. These are works of art that were made for the Pyramid Club, for Wigstock, for advertising drag shows. It sounds like there was a really interesting thing going on where it was “all hands on deck — we’re all putting on a show together,” but also about standing out and positioning yourself to pop off for stardom.

But for instance, here’s an interesting thing. I did many backdrops, so since I knew what the backdrop and the colors were going to be, I worked my outfit to go with it. And [Lady] Bunny was always like, “Damn! That’s not fair! That’s not fair!” I did have a little extra artistic oomph to push myself at that.

I recently read Do Everything In the Dark by Gary Indiana where he’s very clearly making fun of the idea of the “Boston School” being a thing.

Oh, I haven’t read that. You have to really dumb it down for the people to understand or explain stuff. I mean, we were all friends. We were all from Boston. Why not call it the “Boston School”? And it worked for museums. What’s the next show going to me? How about the Boston School?

Did it mean anything for you apart from branding?

It helped to be included! Especially since for the most part they’re all photographers. Like Jack [Pierson] and Mark [Morrisroe] did other things too, but they were always pushing that photography. I was sort of an outsider in that group and yet at the same time I was the model or the muse for all of them. Not the only muse, but I was like the linchpin of that whole thing.

There are many great photos of you.

Every photographer had one of their best pictures of me, yeah? And we were all friends, and we were all growing up together and starting things together.

You kind of come from two different backgrounds, right? Two different scenes that at one point or another became very, very big. The art world blows up and eventually drag becomes a whole big industry as well.

I kind of see it all just as “culture” and everyone likes to say, “This is one thing and this is another thing.” I know a lot of people in the art world never even heard of any of the major references from the drag world. A lot of the drag world has no idea about the art world. But there are a lot of people who are invested in all of it, the music world, the art world, the culture world, the restaurant world, the drag world, the performing world, the Broadway world, the music world. And I like to get my hands on all of them.

I think of you almost as somebody like Keith Haring, right? You’re somebody who can bop around in all these different worlds and your style is the thing that binds different threads together. It works in an art world context. It works on the cover of a Deee-Lite album. It works on the Wigstock poster.

I was doing full pages of Sports Illustrated for years. Interview magazine, Entertainment Weekly, you know, pop stuff, cultural stuff, art stuff. Why not get whatever change you can get? Very few doors open up in any field unless you know someone. It helps if you’re good, but say the art world dies down a bit then I’ll do the theater world; that dies down, you do a lot of graphic design; that dies down, you go back to art. Just keep it coming.

I love your calligraphy. The way you write letters and words is so beautiful. How did you come to that style of making words so pretty?

It’s funny because I think it goes back to when you used to have to study penmanship. Like in even one of my paintings, “Jane Is Sexy” (1981), which has the yellow lined paper, you have to do the middle of the E in the middle of the line. I don’t know if you remember that kind of stuff. But I was always flunking my penmanship. I’d have to stay after class and write 100,000 times and it’s funny that now I get paid for that. I always liked a lot of cartoons that wrote like that.

What kind of cartoons were you looking at?

A lot of those Bullwinkle shows… all that stuff. It’s very Borscht Belt humor, very New York twisted humor, but also very light and funny as a fairy tale. The Addams Family. Aubrey Beardsley, all the art nouveau stuff. Then by the time I was a teenager, it was all like the psychedelic ’60s stuff and the album covers and the poster art. But by the ’80s, that had all gone away and it was a different whole, linear type. And so especially at PAPER magazine, they started advertising in PAPER, and [founder] Kim [Hastreiter] would hold them up: “try to make your ads more like Tabboo!’s” Everything was black and white, so I made them boldly black and white, and then the curl caught your eye. Mine jump off the page.

One thing that seems common to both your drag performance and also the figures you depict, is that everybody becomes a drag queen. When you have a subject in front of you, how do you think about them to make them a little bit more fabulous?

When I was a kid I was a professional puppeteer, so everyone’s sort of like a puppet. I like making my own little papier-maché puppets. I would get commissioned, “Do Bonnie Raitt.” And say we had a club night, everyone has to pick up a diva to perform as and you’re playing Bonnie Raitt. So I would think, How would I play Bonnie Raitt? And that would be how I would draw her. Even if it were characters in Sports Illustrated, they come out as a puppet. I did make-up for some movies and they would always say, “Do my makeup.” I’d say just do your own makeup. Then they’d say, “Oh, no, you. I want you to do your makeup, because you make me look like a marionette. Like I’m one of your puppets!”

It’s funny because you do see so many Drag Race girls today, have this kind of makeup book that is so marionette. I find your influence in all different places in the culture today. Do you see your influence spread out elsewhere?

Oh yeah, I’ve always seen it. And then a lot of people say, “Why aren’t you suing them?” I’m like, this is just creativity, it comes out of me from somewhere in the universe, I just do it. If someone’s inspired by it and they want to copy me exactly, it’s a little like, you could have called me, I would have probably done it for free. Way back, I could see my influence on the Janet Jackson albums, or David Bowie or Paula Abdul or The Cure. Did you do The Cure? No, I didn’t do that one. Everyone thinks I did all these things. And sometimes things pop up that are actually from the ’60s that look like I’m copying them.

Even when Deee-Lite got so big, like, at the very beginning, I didn’t think it would be so big, because at that point, the underground world was slowly coming up. Even with RuPaul, whoever thought she would have more Emmys than anyone else in the world? Have shows in every single language? That enormity of it never really was something you could think would ever really happen.

Isn’t that also true too about art world stuff? It seems like a lot of your friends also have these footprints that are just as big as Nan Goldin going to the Oscars and things like that.

Yeah, that movie that I was in was nominated for an Oscar. She didn’t win, but yeah. Anohni was nominated for an Oscar. She was in Black Lips at the Pyramid. Recently, they’re allowing the underground or the queer community or whatever to have a seat at the table. But one of the great things about Nan Goldin being so big is that she always spelled my name correctly. So in the art world, people already knew how to spell my name correctly. I’m just getting my big, big art world success, but now they’ve already had a proper name.

When I think about the ’90s and so much of the culture that comes from that time, one thing that you see is that the work is both really fun and energetic, but then a lot of it also really sad.

What my work is?

Well I don’t think yours is, but a lot of other people’s work certainly is.

I’m always a positive seed. A lot of my cityscapes might have a quiet meditation feel, they might have a little bit of melancholy. But it’s not like it’s sad stuff, right? Even, for instance, in the show where I’m talking about these different people and how they died — this one died of AIDS, this one died suicide — they’re kind of silly in their own little way with the way they’re done. Life is to be enjoyed.

I really liked those paintings, but I was going to ask you if you were making fun of Basquiat with those because of the crown on the skull.

No, that would be Ethyl [Eichelberger], I think, because we were in a play called Hamlette and she played the king and the queen, and she had a crown on her head. That had nothing to do with Basquiat. Before I even moved to New York, I knew his stuff, because he would do illustrations in Interview. When I first came to New York, the very first person I met was him.

How was he?

Quiet. He was at White Columns, like three different versions ago. Him and Ann Craig, who booked acts for the Pyramid Club, would do a show. He was in a hula skirt, and she was maybe playing a xylophone? It was a kooky little performance art thing.

I would never have thought of Basquiat as being goofy like that. I love that because people weren’t so self-serious about their brand and persona.

I think he was actually known as “Samo” back then, that was his fine performing name, or his graffiti name. They really want to just make you like a “serious artist.” I’m not saying he’s not a serious artist, or that I’m not a serious artist. Like, I guess I could go back and use “Stephen David Tashjian.” Initially I thought no one’s going to take me seriously if I don’t use my government name. Everybody knew me as “Tabboo!” and they would not even know that that was the same person that did both. So then I just said, “Fuck it, just name everything Tabboo!” It’s not even a drag name, it’s not even a female name, it’s just a word.

Could you talk a bit about your landscapes?

Well, I like to paint. I love nature. I grew up in a rural neighborhood at the end of a dirt road by a reservoir. Yeah, it’s funny, because when the internet came, it sort of erased all the galleries, a lot of my whole career was sort of just whoosh and then you have to start fresh. I’m not starting fresh. One of the great things about this show is that they’re showing it like 50 years ago. The art world is a fickle thing.

You said something really funny earlier about being a serious artist. Do you think of yourself as a serious artist? And what would that mean to you?

I guess I approach life in a light-hearted way. Maybe, yeah, but it’s very serious. Life is serious and art is serious, and when I’m making it, it’s usually by myself. So it’s very meditative, but it’s also fun. To make art is a real fun thing. Everyone wants to be a pop star or everyone wants to be Beyoncé. You know how much work it is to be her? But if it’s Beyonce, she can love her job, because look what she’s doing. You know what I mean? So that’s how I feel, very lucky.