April 4, 2025

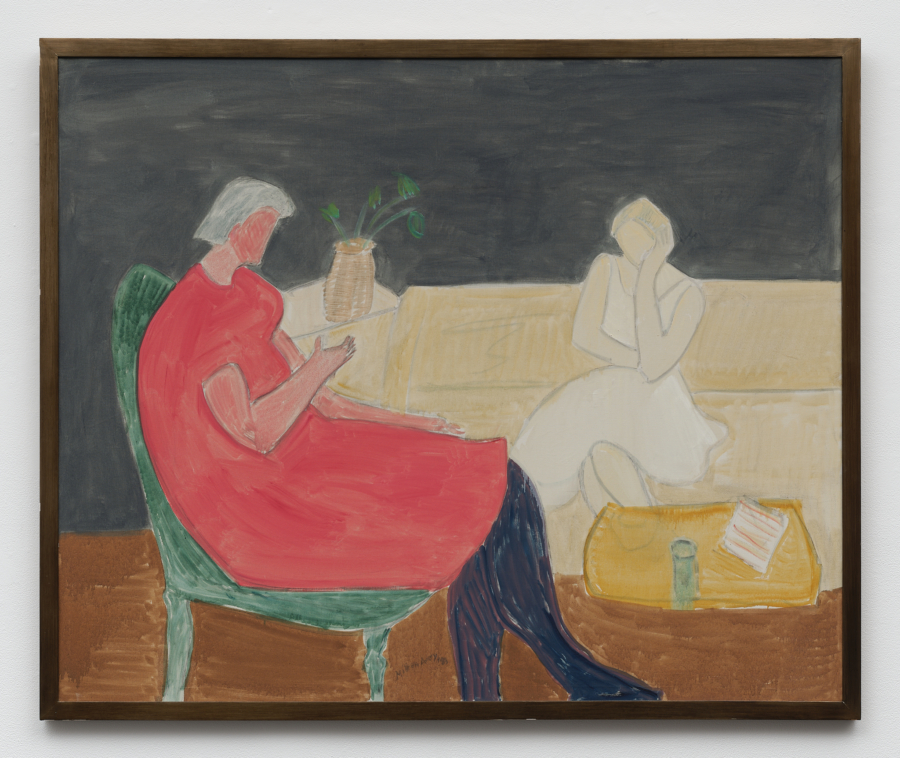

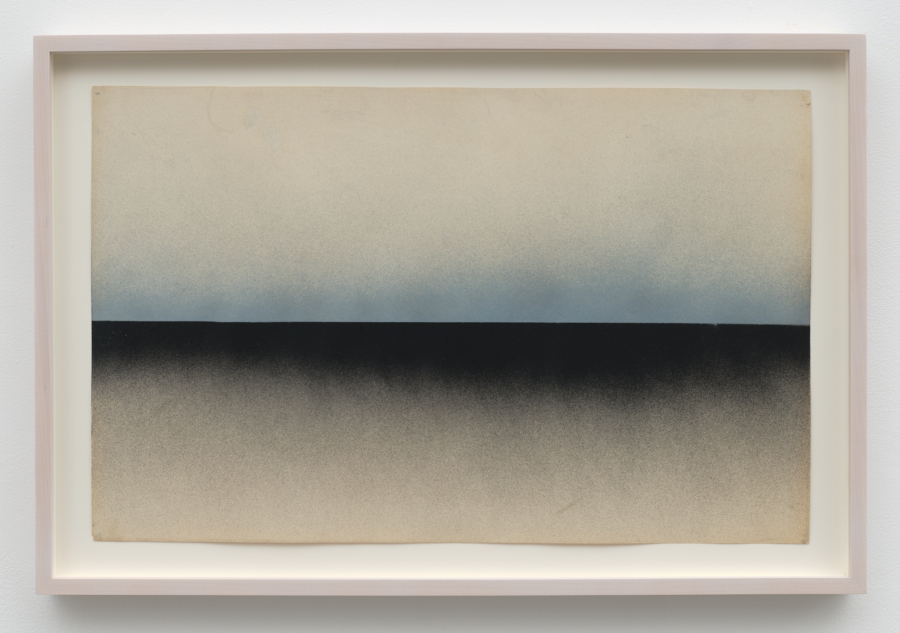

Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori, My Country, 2010. Acrylic on linen, 39 5⁄8 × 77 1⁄8 inches. Courtesy Karma.

Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori’s solo exhibition at Karma in Chelsea (her first in New York), provides an introduction to the work of one of Australia’s leading Indigenous painters. Gabori, who died in 2015 around the age of ninety (her birth date is unclear) took up art in her early eighties while undergoing occupational therapy at Mornington Island’s Arts and Crafts Centre. She approached painting with the utmost focus and commitment, producing over two thousand works until she was physically incapable of continuing. Her large-scale paintings (some are nearly twenty feet long) are freely brushed, expressive, and intensely colorful. They appear to be fully abstract, but are, at heart, referential—anchored to land, memory, and to the complex experience of exile and displacement. While her paintings do not outwardly resemble those of the more familiar Aboriginal desert dot artists, their deeper motivations, social structuring, and emotional tenor are quite similar. Gabori differs in that she came from a group of people, the Kaiadilt, blessed with a resonant language, but with no preexisting graphic vocabulary—no tradition of sand, bark, or body painting, much less easel painting. Her work looks unlike other Australian Indigenous art because it is: she invented it.

The animating thread that runs through her work is the larger idea of “country,” a word that occurs in many of her paintings’ titles. “Country” speaks of place and its inherited custodianship; also of work, identity, language, and family. It is intimately connected to the site of one’s birth as well as the place and the mythic entities associated with a person’s spiritual conception. The idea of country is entwined with the topography of the land, of course, but also how one moves through it, a compilation of one’s shifting physical orientation—something that Gabori’s language, Kayardild (one of the most complex, grammatically case-rich languages in the world) naturally facilitates. The sense of abstracted physical passage superimposed on a simplified yet chromatically active ground is shown to great effect in her shimmering red, black, and white painting My Country (2010), a landscape hovering between declarative presence and evocative absence.

Gabori came from the northern, tropical part of Australia. She was born on the small, flat, and remote Bentinck Island in the Gulf of Carpentaria. In the late 1940s, after storms ravaged the island and destroyed the freshwater supply, the Kaiadilt people (numbering no more than 125 at their peak) were forcibly removed by Presbyterian missionaries to the larger but almost equally isolated Mornington Island, a displacement (accompanied by language loss and family separation) that is echoed in the histories of so many other Australian Aboriginal peoples. The move was traumatic. Children were separated from their parents and forbidden to speak their native language. Especially upsetting was that the Kaiadilt, perceived as outsiders living in another group’s country, were dependent on that group’s good will.

Gabori never forgot her lost homeland, and her paintings continually evoke it. She depicts Bentinck’s landscapes, its rivers, shorelines, and tidal flux, its freshwater ponds, saltpans, reefs, and mangrove swamps, using—for want of a better term—the language of color-based gestural abstraction. Those landscapes are not neutrally observed geographical features, but rather they map Kaiadilt creation stories, as well as the sites of specific work and food collecting routines, like the stone fish traps that ring the island or the ponds where she once gathered waterlilies. They also speak to the places and lives of people she was close to, like the rivers near where she, her husband, and members of her family were born. Gabori’s paintings, while intimately connected to her and her people’s history, myths, and daily activities, are, by virtue of their formal power and sheer beauty, perceptually accessible to us. In Rock Cod Story Place – Freshwater (2005), for example, with its feathered and loosely sprung vertically nested bands, picked out in glowing maroon, pink, vermillion, cobalt blue, black, white, ochre, gray, and yellow, we get the sense of the vibrating, penned-in force of the totemic rock cod, resting somewhere beneath the surface of this “story place” (the English term the Kaiadilt used to denote a sacred site). A long horizontal with layered rectangles of purple, turquoise, and bright red, My Father’s Country / Thundi Big River (2008) is set down on landscape-like zones of bright blue, orange, deep red, and golden yellow, evoking the experience of moving through a complex, emotionally charged place.

Gabori’s work is not a product of modernist gestural abstraction, though it shares certain affinities. That her painting seems connected to bodies of contemporary art with which she was unfamiliar points to an increasingly important synchronic view of the art of today: joined by conjunction and fortuity rather than by history, influence, or lineage, congruities emerge simultaneously. This is key to the reception and reading of the work of art makers like Martin Ramírez, Hilma af Klint, or the Gee’s Bend quilters, among others. Given its visceral appeal, it is unsurprising that Gabori’s work has been widely collected and exhibited in Australia and New Zealand, and increasingly in Europe, where she was the subject of a 2022 retrospective at the Fondation Cartier in Paris, as well as in the US. We can only hope for more such revelations as art becomes increasingly global.