October 22, 2019

Download as PDF

View on Los Angeles Times

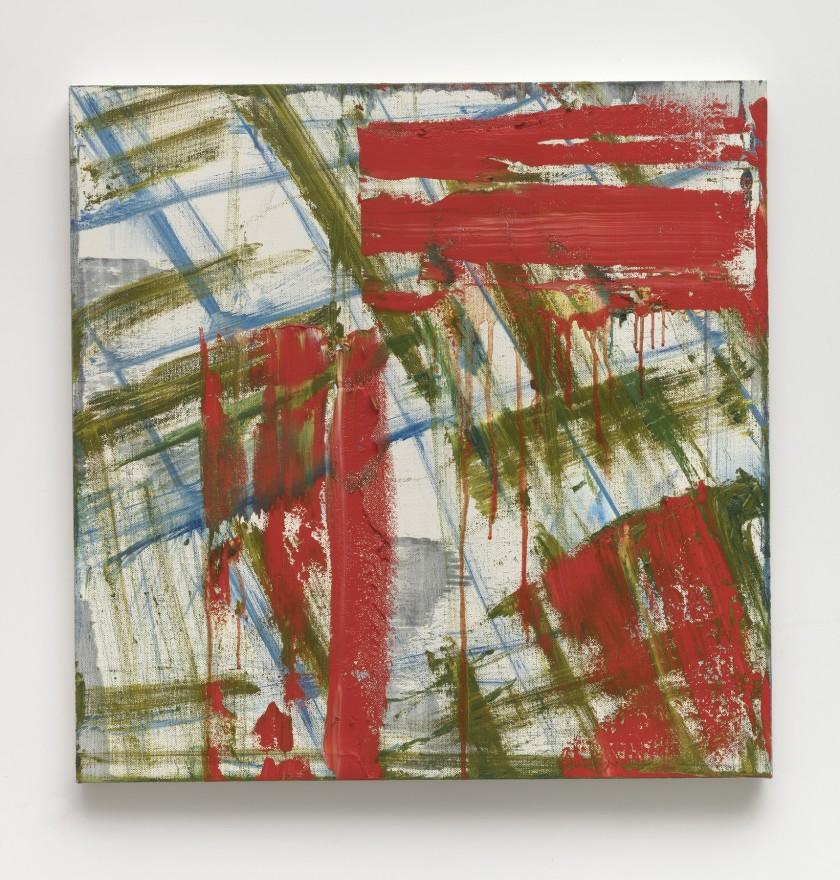

“A Rush of Hard Consonants” by Louise Fishman, 2018. Oil on linen, 30 inches by 30 inches.

Much that is written about painter Louise Fishman begins with biography. The human story never gets old or repeats, but it also can impose a filter that prevents your eyes from seeing and your body from experiencing an artist’s work without preconception. Fresh encounter is precious and true. You can learn the back story later, but you can’t unlearn it if it’s there from the start.

Such was my gratitude that I hadn’t done my homework before visiting Fishman’s show at Vielmetter. The New York-based artist is 80 and has had a highly distinguished career, but her work was only vaguely familiar to me. Her last solo show in L.A. was 15 years ago, and I had seen only a smattering of pieces in group exhibitions. I felt shamefully late to the game and yet exhilarated to be discovering just what a vital game she is playing.

“Frigg” (2018) is the painting that ensnared me. Unlike most of the other recent work in the show, it is largely monochrome, black and white, with touches of blue, green and yellow. Its range of textures and tempos is as broad as its palette is narrow. Black paint rushes across the canvas in wide horizontal sweeps and two central diagonals. It weighs upon the surface in shorter strokes and slabs that are as dense and thick as asphalt. Dilute drips of grayish green course down to the bottom edge.

Some passages look scraped, leaving a thin layer of paint that sets the weave of the canvas into relief. In other places, delicate white ridges rise where a patterned object has been pressed into the wet paint and lifted. Fishman is sculpting motion and time here in stark, dynamic, immersive terms. “Frigg” has the quality of film, as of a landscape shot from a passing car and blurred by memory.

Louise Fishman’s “Frigg,” 2018. Oil on linen, 74 inches by 86 inches.

Perhaps “Frigg” was inspired by travels, perhaps by personal travails. “The Tumult in the Heart” is the show’s overall title, reinforcing a sense of the work as interiority externalized. Fishman’s work may be process-driven, but her process encompasses questions about self, culture and history as much as materials, color and surface.

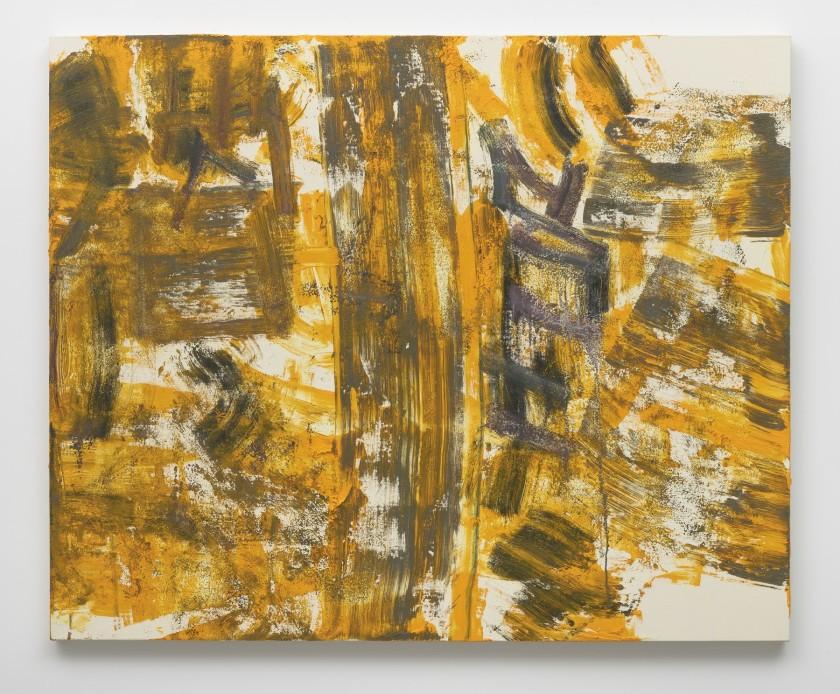

Many of the paintings here reckon with the grid in some way, through its statement and its subversion, declaration and deviation. Fishman’s gestures tend to be athletic. (Note the bold stroke bifurcating “Mixed Weather.”) But she can also exercise restraint. The primed canvas of “Like Air I’ll Rise” serves as a blank slate to sparing marks of calligraphic urgency.

“Mixed Weather” by Louise Fishman, 2019. Oil on linen, 57 inches by 70 inches.

“Like Air I’ll Rise” by Louise Fishman, 2018. Oil on linen, 74 inches by 86 inches.

Fishman has made geometric paintings, “Angry” paintings, works themed on Jewish identity and Holocaust remembrance, and images inspired by light, water and the natural world. She has borrowed from Franz Kline as from Joan Mitchell and J.M.W. Turner, and her sensibility has been nourished by poetry, music and meditation. She identifies as a feminist lesbian and has done her mighty part to help the male-dominated idiom of abstract expressionism come out, as she put it, “as an appropriate language for me as a queer … a language appropriate to being separate.” The vigor of her practice is formidable. The intensity and surprise of each painting simply don’t diminish.