March 16, 2021

Download as PDF

View on Hyperallergic

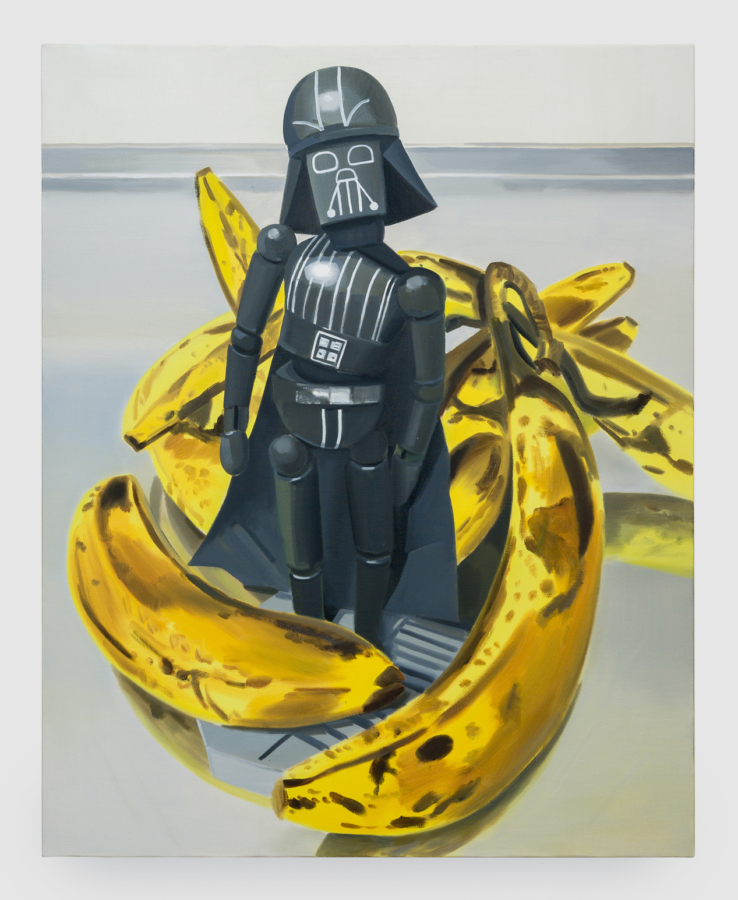

Ulala Imai, “Banana Ambassador” (2021), oil on canvas, 39 3⁄8 × 31 5⁄8 × 1 inches (all images courtesy Nonaka-Hill)

Ulala Imai does more than project human feelings onto toys; she proposes that they represent us, and that we share some of their qualities.

LOS ANGELES — “Bananas don’t really go with Darth Vader, except in parenthood.” The statement begins the press release for Ulala Imai’s current solo exhibition, Amazing, at Nonaka-Hill, the Japanese painter’s first in the United States.

“Banana Ambassador” (2021) portrays a Darth Vader action figure standing amid a bunch of bananas. The figure’s cocked head and yielding posture welcome the viewer, yet Imai’s choice of Darth Vader as the ambassador suggests an underlying menace, though the circle of bananas surrounding the figure reassuringly hems him in.

The story of Darth Vader is also the story of a parent and child at odds with one another, and the parent’s failure in the eyes of the child. The painting posits family as a site of tension between love and duty, intimacy and alienation.

If “Banana Ambassador,” installed in a hallway at the center of the gallery, directly facing its storefront windows, provides a key to the show, the remaining 27 oil paintings expand on the nuances of family as a unit that both envelops and constricts.

“Melody” (2020) depicts a pale yellow teddy bear lain across a banana as if it’s a recliner, but the bear’s body is too long and rigid to fit snugly. The bear appears in several other works, accompanied by a stuffed monkey with a broad smile in “Hold” and “Promenade” (both 2020). In the former, the monkey cradles its companion’s horizontal body, which faces the viewer. The bear’s blank eyes and downturned mouth translate its stiff, awkward features into an unexpectedly jarring, and emotional, expression of discomfort.

The latter shows the couple on a walk with their pet: a potato attached to a chain draped over the bear’s paw; a blue-and-white striped tablecloth provides a pathway and bamboo plant becomes the foliage around them. In relation to the wildly grinning monkey’s oppressive embrace of the hapless bear, the “pet” potato doubles as a darkly comic send-up of a partner as a “ball and chain.”

These troubling dynamics add gravity to Imai’s whimsical creatures. What makes them relatable is that the drama and emotional intensity of her staged scenarios are rife with symbols of everyday life, as in “Distance” (2020), a family portrait of a bear in a bathrobe and its “children” (the ubiquitous yellow bear and an E.T. doll in a red hoodie), or in the many small paintings of food.

Fruits arranged in a dish or on a countertop call upon the history of European still life painting, and Imai’s soft, broad brushstrokes and vibrant colors evoke Cézanne’s luminous apples. Yet her preferences also encompass toast or ham and eggs, while two paintings of halved pineapples with faces made of grapes (“Madame Pineapple,” “Mr. Pineapple,” both 2021) pointedly reflect the daily chore of feeding young children.

“Avocado Rock” (2020) embodies the sometimes smothering security of family: domestic items, including a banana, a bottle of Grand Marnier, a honey bear, and hand sanitizer (one of the show’s only direct nods to the pandemic) are loosely arranged on a reflective countertop around a Chewbacca mask. The mask reframes the still life as a narrative painting, with Chewbacca as the weary family man, his intergalactic adventures, like Darth Vader’s, dulled by exhaustion and responsibilities.

The arrangement of the objects, all contained within the picture plane but not close enough to indicate intimacy, underscores the sense of ambivalence toward family that Chewbacca seems to express. (In contrast, the overabundance of toys in the jam-packed “Gathering,” 2020, conveys stifling intimacy.)

Nearby, three large paintings centered on Charlie Brown and Lucy van Pelt cast the Peanuts characters as friends and lovers. The Peanuts paintings activate the emotional tension that pervades the show. They could depict a fantasy of reconciliation between the two, whose relationship in the comic strip is usually adversarial. Yet it’s nearly impossible for anyone who knows the cartoons to miss their history of antagonism and angst.

While it’s reasonable to project human feelings and family dynamics onto toys, they are not simply symbols or avatars of real people. Imai creates more ambiguity, proposing that they represent us, and that we share some of their qualities.

Their stiffness, their mask-like gazes (some are literally masks), and the “togetherness” thrust upon them by Imai’s arrangements and imposed narratives foreground how our lives are shaped by situations and by others. The toys reflect the obstruction of personal agency and need to don masks in society. Family, Imai suggests, offers a warm respite, but it is edged with the anxiety of needing each other, for better or worse.