It’s a thrilling exhibition, and last Thursday night, it delivered a reinvention of Chicken by Alex Da Corte, the 39-year-old Philadelphia artist whose videos were a starring attraction at last year’s Venice Biennale. As the temperature dropped, people streamed quickly into the former home of the Y—now Gershman Hall, a four-story neoclassical brick pile owned by the university—to see what he had created.

Yellow signs labeled “CHICKEN” pointed the way to the auditorium. “If you want to see everything, go to the balcony,” an usher advised. “If you want to be in it, go to the ground floor.” Inside, the chairs had been removed from the orchestra level, the room was blanketed in yellow light, and a four-piece band was playing gentle drones. Oddly, there were no chickens in sight.

In one corner, a man in a spherical white outfit (Andrew Smith) stood in a cage, reading a blank newspaper. Scattered around the space were six platforms, on which women in yellow outfits sat, accompanied by signs (“A CLEAN MOON FOR A CHANGE!” “MOON ROCKS!”) and props (lab equipment, stacked egg cartons). They looked like carnival barkers taking meditation breaks. Audience members peered down from the balcony, giving those down below the distinct impression of being gladiators in a Roman coliseum. It felt like all hell is about to break loose.

And there was Kaprow himself! He was instantly recognizable with his fulsome beard and bushy eyebrows, wearing a vest, jeans, and well-worn brown boots. (It was Da Corte, after hours of makeup work.) Suddenly a spotlight was on him, and he had an announcement: “In the words of the great Joe Brainard, I remember Chicken.” And with that, the music turned threatening—sawing strings, as in a slasher film’s soundtrack—and Kaprow was twirling his index fingers in the air, a bit like a superhero villain orchestrating chaos.

The women took turns selling various moon products with high-energy menace. One (Julia Eichten) fired up a vacuum cleaner, shouting as she dusted a huge white bouncy ball. “Don’t you feel shiny?!” she growled. “Don’t you feel light?! Isn’t it good to be white?!”

“You look sad!” another (Jessica Emmanuel) crowed, liquid bubbling in beakers before her. “You look depressed! You look miserable!” It was the moon’s fault, she explained. “If you’re broke: moon! If you’re lonely: moon!”

A purveyor of moon rocks tossed her products—whole eggs, which splattered all over. “Everybody gets a moon rock today! You get one, and you get one, and you get one!”

The barkers started going at it together, some tossing orbs to the audience. Then a red light hit the stage, and it all was still. A performer glided through the curtains in an angular top and skirt, a wide-brimmed hat, and kitten heels—everything red. It was the dancer Imma, and after slinking down the stairs, they cut through the crowd, scampering to a speedy techno track, pushing over a table stacked with milk crates, unleashing chaos.

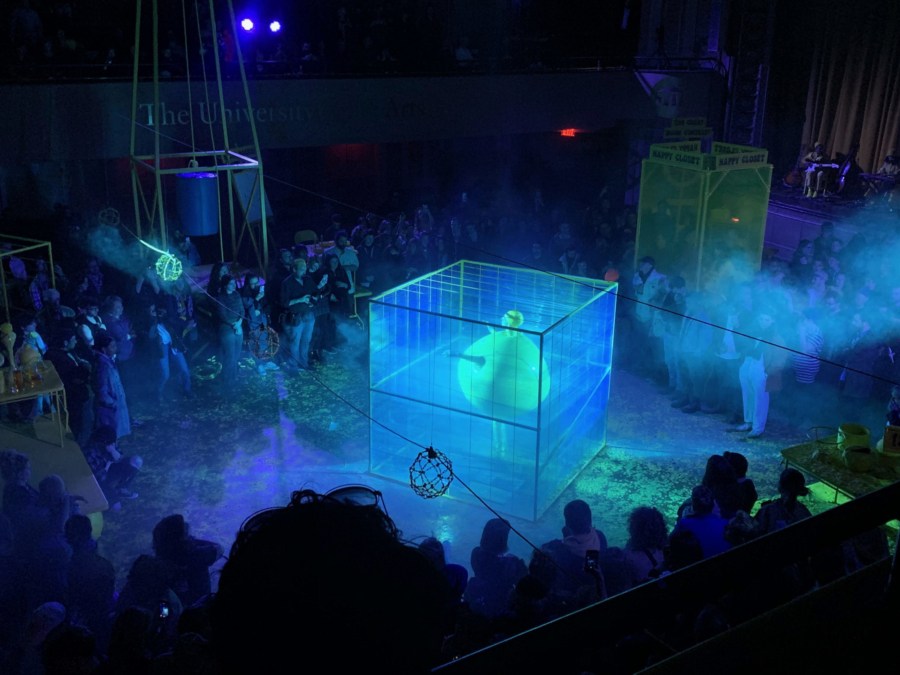

Lastly, blue light! The women moved on the man reading the newspaper, pushing his cage to the center. Performers in blue sprayed it with fire extinguishers, the moon man inside shaking slowly. Kaprow was on stage again. “Ladies and gentlepeople, the sky has fallen,” he said, sounding a little forlorn. He suggested that people go home and call their mother, “our lady moonlight, and tell her that you love her. Happy Halloween. And good night.”

The crowd lingered. There had been no chickens, but there had been moments of terrifying salesmanship, dizzying violence, and total pandemonium barely pulled back into order—all very American things (at the risk of putting too fine a point on it), assembled over one ingenious, harrowing, entrancing hour.

“I’m still in shock,” Da Corte tells me by phone a few days after the show. “I had never done a live performance before.” Processing it all, he’s been thinking about how “it was a punk show, it was a rave, it was a comedy show, it was so many different things.”

No further performances are planned, even though he worked on it for four years, studying the details of the 1962 original. “The only thing I replaced was instead of a chicken it was this orb, the moon,” he says.

“In my imagination, when we think of an egg, we think of the yellow yolk inside,” Da Corte says, explaining how he came to focus on the moon. “There’s a funny slippage that occurs there, where, in seeing the outside of something you’re also imagining the inside at the same time. I think that’s beautiful.”

The veteran Phili artist Rosalyn Drexler penned the show’s treatment, and choreographer Kate Watson-Wallace marshaled performers and charted possibilities for movement. “It was a deeply collaborative effort with so many people,” Da Corte says. About 20 performers brought it to life. Since then, “we’ve been on this text chain discussing it and saying, Jeez, we see yellow everywhere we go,” he says, “really missing each other in this strange moment we’ve created. I think for me it was singularly quite life changing. I still have no words to describe it. It was just deeply moving for all of us.”

One suspects that Kaprow, who died in 2006 at the age of 78, might have understood what they are going through. He certainly would have admired it. In a 1966 lecture, he said, “A happening is for those who happen in this world, for those who don’t want to stand off and just look.” Later, he put it another way, arguing that “happeners have a plan and go ahead and carry it out. To use an old expression, they don’t merely dig the scene, they make it.”