October 17, 2019

Download as PDF

View on Brooklyn Rail

A vase of orange marigolds adorns a ledge at the entrance of Alex Da Corte’s second solo show at Karma. Like the artist’s work, this little detail cloaks meaning in layers of wit. The marigolds’ striking golden hue symbolizes both fortune and grief. Known for captivating films and installations that probe popular American culture, Da Corte is acutely sensitive to the myriad signifying effects of both color and cultural imagery and uses them to penetrate our individual experiences and collective associations.

Alex Da Corte, The Pied Piper, 2019. Neoprene, EPS foam, upholstery foam, staples, thread, polyester fiber, epoxy clay, MDF, plywood, 120 × 120 × 6 1⁄2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Karma, New York.

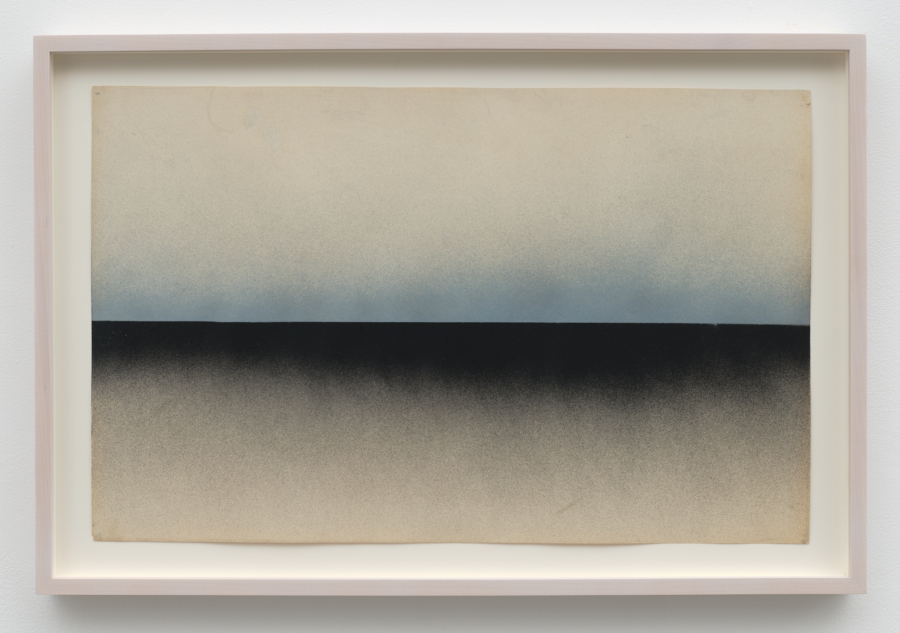

Marigolds is split between neighboring gallery spaces. In the first are 10 facsimiles of vintage cartoons and magazine covers that Da Corte modified with white paint to isolate details, such as a carrot-shaped flute on the cover of a Bugs Bunny comic book or a bucket of paint rigged over an unsuspecting victim in an old issue of Pat Sullivan’s Felix. Each is presented in a hand-sculpted epoxy frame of blue, red, yellow, green or black. The modeled surface of the frames and the overlaid images recall children’s play-dough sculptures and their wanton scribbles in comic books. But hung at eye level and spaced throughout the room, cartoon characters are refashioned as makeshift icons. Through his modifications, Da Corte undermines his sources’ narrative in order to toy with their larger cultural role. This reaches beyond the cynicism of Pop and the detachment of pastiche to open up a space to examine the implicit cultural faith placed in cartoons, television characters, and popular icons.

In the neighboring gallery, six massive, batting-stuffed neoprene renderings of the isolated details hang on the walls. Bugs Bunny’s carrot-shaped flute becomes The Pied Piper (2019) and the cover of Felix with his rigged can of paint is now Creeping Death (2019). Expertly uncanny, they are at once garish, frightening, and comfortingly familiar. White and yellow light emanates from a neon tube on the ceiling, shrewdly placed near the skylight. The naturally lit room is muddied with ersatz light, matched in nauseating effect only by the slick floor—which is, of course, painted marigold yellow. The use of color and light that often animates Da Corte’s installations has grown more subtle and effective in this most recent show. You do not expect the discomfort that comes from sitting on the brightly colored steel bench snaking through the room. It creeps up on you slowly.

Alex Da Corte, Blue Pencil Drawing (Cover The Earth), 2019. Inkjet and White Out on paper, cast polyester resin frame, plexiglass, mat-board, coroplast, wooden strainer, hardware17 3⁄16 × 14 13⁄16 inches. Courtesy the artist and Karma, New York.

Susan Sontag wrote in “Notes on Camp” (1964) that “to perceive Camp in objects and persons is to understand Being-as-Playing-a-Role. It is the farthest extension … of the metaphor of life as theater.” Camp, then, is to inhabit a character as if fiction were truer than reality. In Da Corte’s world, Camp is exerted to its utmost. Color performs, making full use of its duplicitous nature. Like marigolds, the color yellow signifies both good and evil. It is auspicious and joyful but can also evoke deceit and dishonesty. The room itself is both beguiling and off-putting, and the saturated colors of the neoprene mutate as one bathes in the neon light. In Camp fashion, the cartoons are so aware of playing a role that a snipped detail takes on its own life as a bizarre, larger-than-life wall hanging.

Husband Pillow (2019), an enormous blue velvet sculpture in the back room, exemplifies the ways that double meaning is not only performed but also socially engendered. According to Tausif Noor’s essay from the accompanying catalog, it is based on an image from the beginning of Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince: a child’s drawing of a boa constrictor that has swallowed an elephant, which adults see as a hat. (“Grown-ups never understand anything by themselves, and it is tiresome for children to be always and forever explaining things to them.”) Re-imagined as an enormous blue plush sculpture, viewers are faced with the fact that the sinister truths that have always been latent within the fictions of childhood.

Like Dr. Eugenia W. Collier’s Depression-era coming of age short story about an impoverished Southern girl that inspired Da Corte, Marigolds goes beyond hinting at the darker truths that children come to understand as they grow into adulthood to suggest they are embedded in the experiences and expressions of innocence. Like art, cartoons are a lie that tells the truth.