August 7, 2017

The Philadelphia artist challenges traditional concepts of good taste

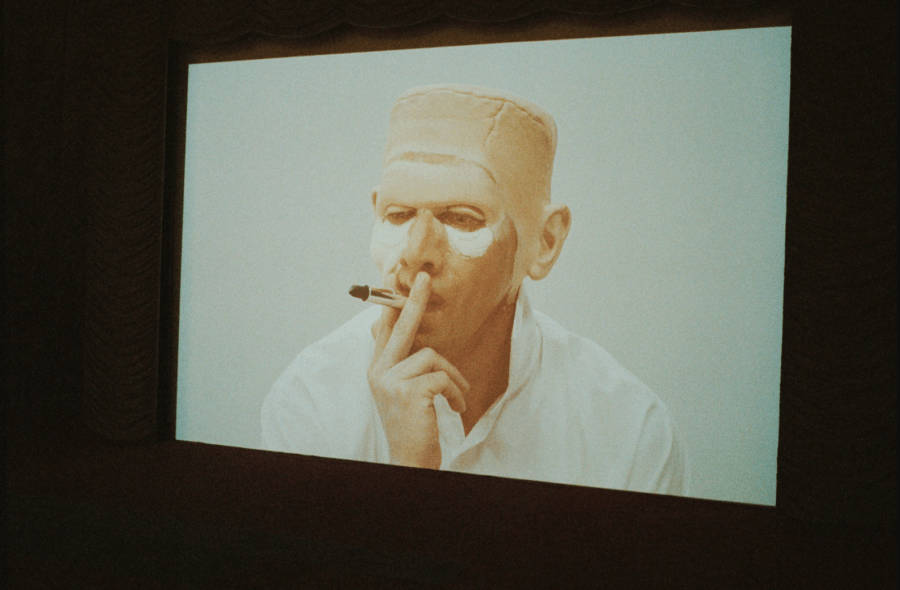

Photo: Lukas Gansterer

Alex Da Corte’s soft-spoken, introspective manner belies the aesthetic maximalism of his artwork. Consisting mostly of sculpture and video, his works are visually vociferous, favoring huge, immersive scales, and employing bright colors, patterns, and pop culture imagery. In less subtle hands, Da Corte’s preferred motifs might become garish and oppressive, but the 36-year-old artist—relying in equal measure on a broad knowledge of art history and a formidable set of instincts—manages instead to make them elegant and emotional, even poignant. His assemblages are formally nebulous—bleeding outwards, while also allowing the outside world in. He rejects the antiquated notion of the sculptural monolith—of artwork in a vacuum.

The artist’s installations are often reminiscent of set design, placing the viewer in the dual positions of consumer and performer. For Free Roses, his recent show at Mass MoCA, Da Corte rendered the museum’s galleries almost unrecognizable, subsumed by his acid- hued, hyper-commercial vision. Stark geometric tessellations, corporate branding, austere, modern furniture, and sumptuous fluorescent light, created a space that was both inviting and alienating, deeply authentic and false.

Da Corte’s project aims to complicate, blur, and erase cultural hierarchies. Within his oeuvre, a cheap, plastic JarJar Binks mask fits perfectly alongside the geometric forms of Sol LeWitt; Coca-Cola and Life Cereal with the poetry of Arthur Rimbaud.

Raised between suburban New Jersey and Caracas, Da Corte’s upbringing powerfully molded his artistic practice. The visual culture of the American middle class—the middle class that was all but non-existent in economically polarized Venezuela—as manifested in big-box retail, has provided the artist with an aesthetic template for his output. His constructed environments, like those of Target or Walmart, engulf their denizens, lulling them with candy-colored neon lighting and corporate branding. The artist’s project is not to decry the evils of these prevalent modes of psychological manipulation, but instead look for bright spots. Challenging traditional concepts of so-called “good taste,” Da Corte celebrates vulgarized materials: the inexpensive, mass-produced, dollar-store products he grew up loving.

Tom Brewer spoke to Da Corte in his studio—located in his beloved city of Philadelphia— following the artist’s return from installing and opening an exhibition at the Vienna Secession.

Photo: Lukas Gansterer.

Tom Brewer

Alex Da Corte

–

So The Secession in Vienna had this Gustav Klimt frieze, it’s called the Beethoven Frieze, and it’s in the basement of the building. It’s the only thing that’s constant there; all the shows rotate but there’s always this frieze. And the frieze wasn’t always in that spot, it was originally built in one of the wings of the main space.

As a temporary space. An exhibition space.

Yeah. They have always had this spirit of constantly moving forward. They want you to do it to the max and, if you can, if you want to fuck it up, then fuck it up.

It’s certainly an unusual attitude — to encourage the undermining of the space — for an institution with that kind of pedigree.

I remember seeing a picture of Isa Genzken’s show there, which was probably around 2004 or 2005, and that was maybe the first image of contemporary art I ever saw. My friend, William Pym, showed me this picture — it was a bunch of cradles and umbrellas, and it was inside this beautiful white space with this beautiful glass ceiling. I assumed all art spaces look like this — totally idyllic. And, well, I was wrong. [Laughs]. But it’s so cool that I can now have a show there, in this place that is totally legendary — not only in art history, but in my own life and development.

Interesting that Isa Genzken was some of the earliest contemporary artwork you saw. That seems to have had a lasting influence.

Absolutely. I was working in Philly at the time. I had just gotten out of undergrad, and I went to a craft school, so I was totally unaware of contemporary art. Whereas graduating from Cooper or SVA I think you’re a little more aware of what’s happening in the world of art. I studied printmaking and we were basically just learning technique and craft; looking at [Albrecht] Dürer. So then you leave school and you’re like, “I can make it very well,” and people say, “Okay, cool, but fuck off.”

So it wasn’t immediately that you figured out that sculpture isn’t necessarily big; that it isn’t just this macho, Minimalist medium.

Right, it isn’t all [Richard] Serra. Which was sort of the impression I was given by the sculpture department at my school. I thought I’d much rather be at home making stuff. I had always wanted to make objects, but the materials I was working with were fake fingernails and sequins — soft things — and I really didn’t feel like I had a place in that conversation. And then William showed me all these people using soft stuff—Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, Isa Genzken. And it really fucked up my brain.

Photo: Lukas Gansterer.

That must have been pretty huge, right? Not only in terms of material, but these artists’ vocabularies, compared to the Minimalists, they’re a lot more expressive and emotional, and a lot more reliant on pre-existing forms. They’re impure.

They’re so impure — they’re using sampling. It’s also about the psyche. Assuming each material is a stand-in for some feeling, and you can mix them around — the way you do with words in poetry.

All those artists are really psychological — and often in the way where the work is funny at first glance and then more disturbing the more you engage with it. I always think of those videos Kelley and McCarthy made together — Family Tyranny/ Cultural Soup — where Paul McCarthy is playing an abusive father and Mike Kelley is the kid. Which sounds really absurd and outlandish, and funny when you read about it, or at least it did to me. Funny, but also horrific.

And in my mind they take place in a wood-paneled room, this weird void.

This suburban non-space.

That’s hell. Or at least, for a lot of people. It’s familiar to me, growing up in Jersey.

What town did you live in in Jersey?

Camden mostly, but a lot of towns. We moved around.

And how long did you live in Venezuela?

Until I was eight. I was born in Camden, then we moved to Venezuela, which is where my father and his family are from.

I was really interested in the idea that maybe you approach art-making in this way that is not typically North American, not European. Especially conceptions of good taste; there’s this idea a lot of us have that good taste is about restraint, that it’s about the redaction of visual information, whereas your work tends more towards the amplification of visual information, turning the volume all the way up on what is already extant.

Well, I don’t necessarily think it’s not North American.

Photo: Lukas Gansterer.

Okay, right. Maybe it’s extremely North American, but it’s not what you usually see at, like, MoMA. There’s a belief that fancy things are fundamentally at odds with the aesthetic of big-box stores.

That definitely comes from my fascination with my parents and their upbringing, and relationship. My parents have been married for forty years. My mom is from the States; my dad is from Portugal and then Venezuela. So there were these two very different cultures that collided when they met in Philadelphia in the 70s. And that’s always been fascinating to me, because in Caracas, Venezuela, there is no middle class.

Just the extremely poor and the extremely rich.

Exactly. And that really affected me growing up. Not enough to understand the meaning of class structure, but enough to comprehend that, when I would see extreme poverty, these shanty-towns on the sides of mountains, that was something really different from my own experience. And it’s not to say that my mom came from gross poverty in the States — her family is just blue collar, middle class. And in terms of values, how the two sides of my family understood material things, it was just very different. It sort of illustrated this dichotomy of city versus suburbs. And I’ve always wanted to advocate for the suburbs, or anything on the periphery.

How do you think that attitude manifests in your work?

Well, around us we would see that there was really high and really low, and there was often this conversation of, “why isn’t there a middle?” Why does it have to be high and low? Why is there an X that says this is good taste, or this is high taste, or this quality of scarf is going to be the best? Or if your taste is so high, can you not eat a peanut butter sandwich? And what’s bad about a peanut butter sandwich, if the peanut butter sandwich was made with love? How do you grade all these other things that might give you a quality of life that might be the best? What is the best? I was privy to a lot of these kinds of conversations between my parents, and I grew up proud, proud of my sandwiches and my thrift store clothes. And I loved this cheap plastic stuff. Not because it was the best, but because it made me happy. I think I’ve learned to love the big box stores I grew up in, and not in an ironic way, but in a real, earnest way.

The influence of the big-box store really informed the way I looked at your work, and especially your Mass MOCA show. Late capitalism is a fact; it’s the world we live in. And there’s a critique of that implicit in your work, but what’s more powerful is that it’s not so much about the horror of the world under late capitalism, of cheap plastic stuff, but about finding humanity in that world.

I’m trying to be a participant. There’s a big difference between participating and watching. Because I do go to Wawa. And I get a cheap sandwich. And it’s fucking good, and I celebrate that. But then there’s still that value system that says, “If you spend more you get more.”

“Nice things cost money.”

Yeah. And that mentality excludes other people. And that stinks. Having felt like an outsider for so much of my life, I never want to make anyone feel that. To me, that’s totally a bullying mentality.

I think that’s one of the more subtle and sinister ways that class stratification operates and manifests: taste. The idea that, if you come from the right kind of background, you learn to place value on the right sorts of things — systems of valuation that, in reality, are culturally constructed, just like everything else. It’s an avenue for othering people.

I recently found myself eating lunch with this older lady. We were eating Caprese salad — you know, mozzarella, olive oil, tomatoes. But the way she was discussing it, she was saying, “You can’t get tomatoes like this in Philadelphia.” And I was thinking, “Well, sure you can. It’s a tomato.” [Laughs] And she was saying, “If I had kids, I would only feed them this. I would never feed them a peanut butter sandwich.” And I was thinking about my sister, who has three kids, and my mom had four kids growing up.

And you all ate peanut butter sandwiches.

We all ate peanut butter sandwiches. And I feel great. We loved peanut butter. You know, it’s great if you put tomatoes and olive oil together, and it becomes Caprese salad, but it’s the same as putting peanut butter and jelly on bread and it becomes a peanut butter sandwich. It’s just about how you look at it. There’s alchemy in everything, you can turn anything into gold. Having just left Vienna, and seeing so much art, and truly feeling maxed out with art — you know, capital A-R-T.

“Fine Art.”

Fine Art, big statues and castles and things that celebrate whiteness. It was really nice to come back to Philly and just be happy with what I have here and say, “Yeah, I really missed this place, with all its grit and grime.” That really keeps me going.

I think a nice thing about a lot of contemporary art, and about your work in particular, is that it aims for this leveling of culture, the dissolution of hierarchies.

Yeah. There’s a lot of smashing icons.

But not just smashing icons, there’s also making new icons, and using the pedestals for the old icons to prop up the new ones.

We’re resisting legacy, pushing up against it. I think about slang a lot. And what’s beautiful about slang is its newness. And what’s strange about it is that newness. It’s not a degradation of language, it’s a mutation, and it’s moving us forward.

Yeah. There’s also the fact that, with slang, people are taking control of language, making it their own. People are creating a time specific, place specific colloquial language that is every bit as powerful as, like, Victorian English.

It’s not necessarily to cancel out whatever mysteries and meanings these pre- existing icons have, but to make them my own, to embrace them and add on to them. It’s about mutating more than erasing.

Iconoclasm doesn’t have to literally mean icon-smashing.

It’s about building on things. Because, otherwise, nothing really can go anywhere. Artists I think about a lot are Ree Morton, Paul Thek, Polly Apfelbaum. Or Karen Kilimnik, a lot of the early stuff she was making.

Philly girl.

Yeah. She’s from Philly. And because of that, hers was some of the first artwork I saw. Her way of making is so free — this kind of “can’t-pin-me-down” way of making.

Well, I think you’ve been very successful in that. It’s never totally clear to me where an artwork of yours begins or ends. And that really casts doubt on the vaunted status of the art object as a discrete thing that can exist in a vacuum.

One of the first things I loved in art was the painting of the last judgment by Michelangelo. And what I loved about it — this is probably really telling — Michelangelo got this commission to make this painting, and all these paintings at this time were meant to inform the masses, and get people to be Christian, and then that was ultimately really about making money for the church. But here is this artist who gets this commission for a painting, and he’s still able to insert this beautiful self-portrait, himself as the flayed skin of St. Bartholomew, and also to paint the rich guy who commissioned him as this ugly demon. So he’s able to work within this paradigm of commissioned painting but also to insert these two jabs to The Man—to participate but also resist and subvert. And that’s the spirit I really want to work in. There’s always room to resist, to ask questions and poke holes in your own practice.