September 27, 2019

Download as PDF

View on Mousse Magazine

You asked me what family is

And I think of family as community

I think of the spaces where you don’t have to shrink yourself

Where you don’t have to pretend or to perform

You can fully show up and be vulnerable

And in silence, completely empty and

That’s completely enough

To show up, as you are, without judgment, without ridicule

Without fear or violence, or policing, or containment

And you can be there and you’re filled all the way up

We get to choose our families

We are not limited by biology

We get to make ourselves

And we get to make our family”

—Blood Orange, “Family,” from Negro Swan (London: Domino Recording Co. Ltd., 2018)

“A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin, and culture is like a tree without roots,” noted Marcus Garvey, Jamaican political activist and pan-Africanist. For what is it that, in the face of difficulties, makes count all of the reasons why we’re not lost in the world? Our families; our extended families; our communities. Identification is key in the making of one’s personality and sensibility: the people we are exposed to and the situations we find ourselves in are the pillars of what we’re made of. Alvaro Barrington knows this all too well and is grateful to all the people who have bequeathed him ways of seeing and being, so much so that he wants to celebrate their preciousness in his life through his work—work whose boundaries are as blurred as it’s natural for them to be.

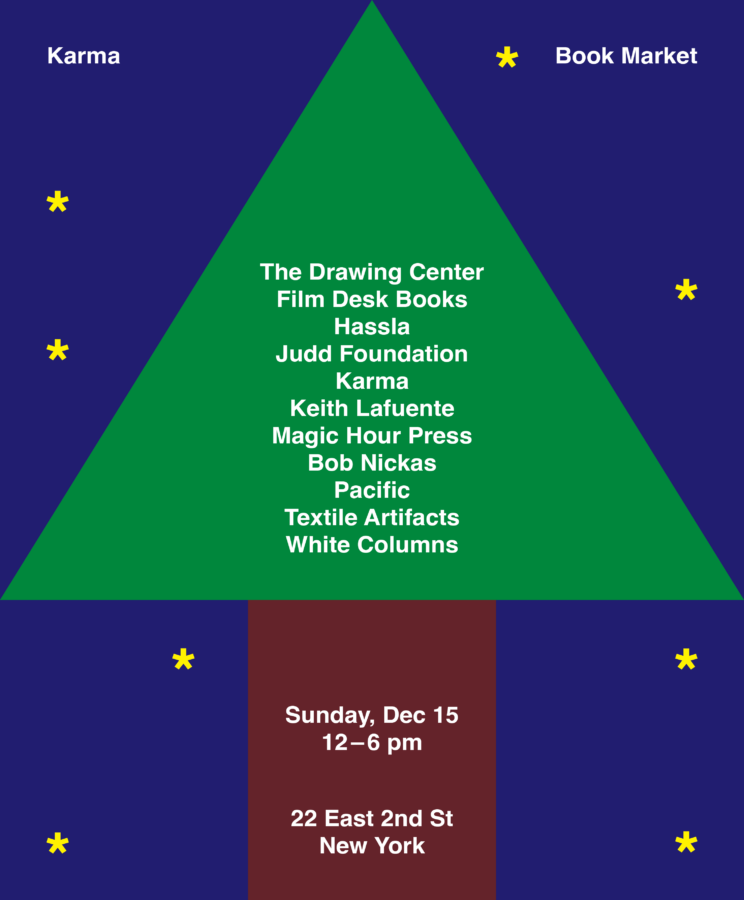

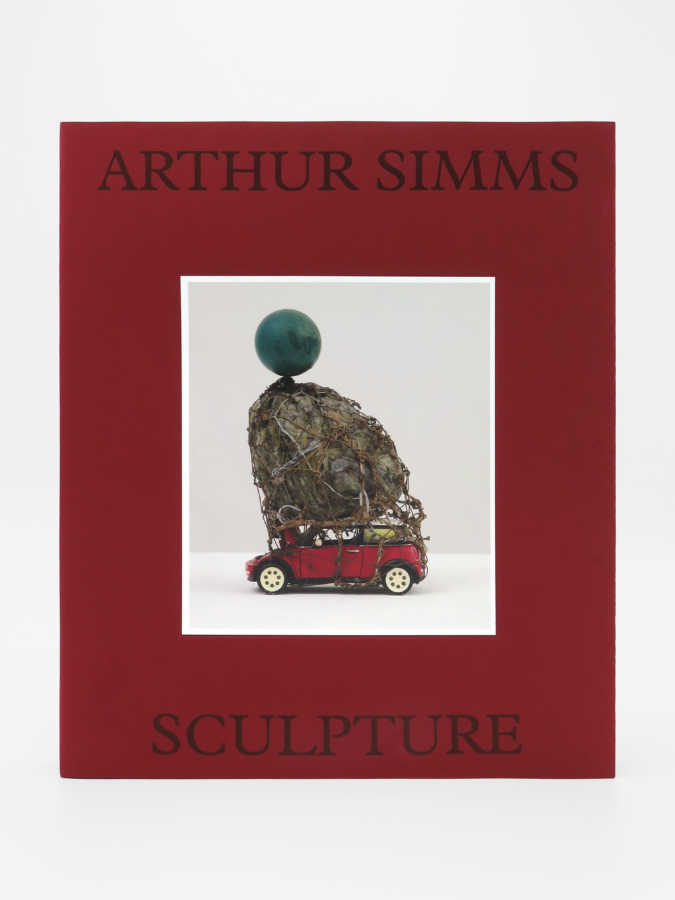

With GARVEY: SEX LOVE NURTURING FAMALAY, currently on view at Sadie Coles HQ, London, Barrington—who lived his early years in the Caribbean before moving to New York as a child—takes Garvey as a starting point to show the outsize contributions black and Caribbean culture have made on the world at large. He also looks at birth, his memories of his mother being pregnant with his younger brother and the ways in which the hip-hop and rap music scenes that flourished around him as a teenager living in Brooklyn have shaped his view of the world. To accompany the show, Barrington worked with independent publisher Pacific to create GARVEY!, a magazine inspired by Word Up! that includes contributions from friends and activists as well as his own writings and images. Barrington also collaborated with Socaholic and the United Colours of Mas to participate in the Notting Hill Carnival. Barrington is a firm believer in the political power of art as a tool to change larger cultural conversations. He calls for introspection through social intimacy because, as he asserts, life can be tough—and we should celebrate the folks in our lives more.

CHIARA MOIOLI: The paintings in GARVEY: SEX LOVE NURTURING FAMALAY are the departure point for a four-show exploration of the life of Marcus Garvey (1887–1940) and his relationships to London, the Caribbean, and New York. Garvey was a Jamaican political activist, a pan-Africanist, the founder of UNIA (Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League), a key influence on Rastafarians, and the first recognized Jamaican national hero, but also a controversial and polarizing figure. He already was a recurrent character in your previous works. What drew you to further investigate his life? What does he represent to you?

ALVARO BARRINGTON: I grew up loving drawing, loving making. I used to draw at every moment and people around me knew me as “the kid who could draw.” Often I was the go-to for anything creative. Somewhere around high school and getting an education and life (I was a horrible student in high school, never went to class, partied a lot), I lost my way and I found myself in situations that were dead-ends. I barely got into college. I had been an A student in junior high—a nerd, very studious—and at nineteen I was a different person. One of my best friends at the time use to say I went “from geek to chic.” I was more concerned with high fashion and girls, but then I wanted to return to the person who lived up to his potential. My last semester in high school, my art history teacher, Ms. Dell, started the class by showing a few artists of color and women artists, and told us that even though the rest of the semester she was going to teach us about Michelangelo, et cetera, women and people of color were creating as well. They weren’t going to be on our state test, which we needed to pass in order to graduate, but she wanted us to know this other part of art history. I graduated high school wanting to find the value in what I loved to do, which was make in relationship to the people I care about.

My elementary and junior high school art teacher, Mr. Ortiz, was a Rasta, and around my way in Flatbush where there was a huge Caribbean American community. One Rasta used to make these sci-fi Caribbean landscape paintings, and he was the first painter I knew. After high school I wanted to return to a younger self who had had possibilities. I made a lot of changes in my life. I bought The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey, I started listening to conscious reggae like Jah Cure and Sizzla—musicians who in the early 2000s were having a moment and breaking into the U.S. market. I started growing my dreads out and Garvey became a gateway for me to begin to understand that black culture, Caribbean culture, the culture I grew up in, had such an impact on the world. Garvey was the father of pan-Africanism and his movement became a catalyst for black folks to understand that their history was way deeper than slavery. His most famous saying is, “A tree without its roots is bound to fall.” We are small islands, but we were creating large conversations with the world.

CM: How did you approach the challenge of recounting black relationships in this show?

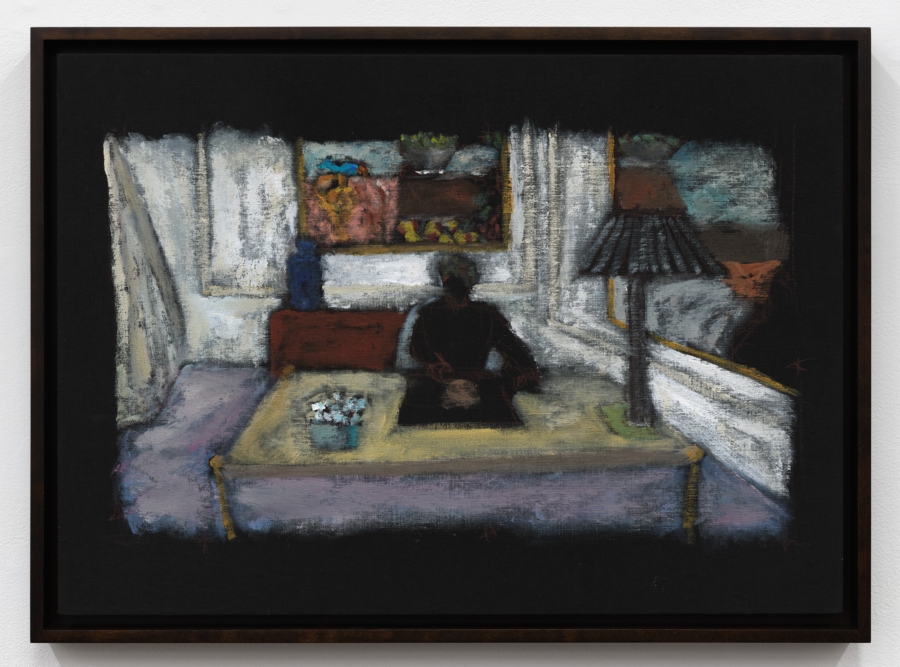

AB: The paintings are about my mother’s relationship to my father and my brother’s father, and her giving birth to my brother, Alex. It’s really about her relationship to men. She passed away right after she had Alex. I never knew her really—I met her when I was seven and she passed away when I was ten, but I watched her being pregnant with Alex and her belly growing and I wanted to make interesting and inventive paintings that told that story and other Afro-Caribbean stories in relationship to artists like Agnes Martin, Helen Frankenthaler, and Louise Bourgeois.

CM: As part of the solo show at Sadie Coles HQ you launched a new publication: GARVEY!. Its title is an obvious reference to the notorious pan-Africanist, while the design of the booklet is a riff on Word Up!, a U.S. magazine focusing on entertainment and music (especially rap, hip-hop, and R&B) that was popular among teens in the 1980s. In line with this, you filled GARVEY! with quotes from rappers’ hits (2Pac, 21 Savage) but instead of giving voice to million-dollar celebrities, you lend the microphone to caring human beings sharing their touching humanness. Could you tell me about the genesis and purpose of GARVEY!?

AB: I think the description “notorious” for Garvey is problematic because it centers the idea of black criminality around a very complicated person and I’m not into defining anyone in such terms. Black folks in America know how violent mass incarceration is because we have positioned black men as criminals for so long that we now have thirteen-year-old kids in jail for life. I think all humans are complicated and shift and hopefully we can begin to no longer define someone by their worst characteristics, like drug addict or whatever, because folks grow and change all the time. But to your question, I have such a wonderful community and interesting folks around me and I meet interesting people all the time. I met the writer Lauren Du Graf on a flight from Paris to New York. I wanted to have these voices heard because these folks help inform who I choose to be, and listening to them makes me understand life deeper.

I got the idea for the magazine when I was at the Rauschenberg residency. Elizabeth Karp-Evans (whose imprint Pacific published GARVEY!) was showing me photos from a show she did and I noticed a publication in one of them, and all of a sudden I knew that a magazine would allow me the freedom that traditional exhibition catalogues don’t. It was exciting because I think magazines are kind of like art now because folks no longer read them the way they used to. Print publications are at a moment where they need to redefine themselves because they are dying. I think this was a great first edition and I’m excited about pushing it in the next edition and really making it a work of art.

CM: Would you discuss the side projects that you produced in collaboration with Socaholic and United Colours of Mas for the recent Notting Hill Carnival?

AB: I grew up going to Carnival in Grenada and in Brooklyn on Labor Day. It was such an important part of being in Brooklyn and it’s always been important to me to maintain that relationship. Notting Hill Carnival is such a big part of London—two million people attend—and I wanted to do something special there. I asked Nadia Valeri from Socaholics and my cousin Fitzgerald Jack, who goes to Carnivals all over the world, what would be special, and they came up with the One Famalay concert, where musicians like Bunji Garlin, Machel Montano, Fay-Ann Lyons and Mr. Killa performed and then we had them perform on the float as well, so it was like a free concert for everyone at Carnival. Growing up in Brooklyn I remember how musicians like Biggie and Lil’ Kim would perform on the Hot 97 floats and then Jay-Z did “Big Pimpin” down at Trinidad Carnival and I wanted to tap into this thing that made being from Brooklyn so special—we wanted to bring it to London for the show, and it was beyond a success. I designed the float for the Colours band and they won first place during Carnival.

CM: Any insight about how the shows dedicated to Marcus Garvey are developing?

AB: Garvey is part of a larger twelve-chapter show happening in London and New York over the next thirty years. I think of it sort of like the Marvel universe starts with Iron Man and then grows to Endgame. Garvey is like Iron Man in that it kicks off the franchise. I kind of already know the overall arc of each show—what keeps it together and how it leads to the next. It’s just about making the work for each show because the twentieth century has already happened and I’m writing about the nuances that have shaped my ideas and life. The first chapter is now on view at Sadie Coles HQ, London, and next year the second chapter will be at Corvi-Mora, London. The show at Sadie Coles focuses on birth; the second chapter is about seeing people; the third chapter is about Garvey at the height of power and in his ego; and finally the last chapter is about his fall and how he regains himself.

CM: “Art is always who we are. It’s about community—sharing ideas through music, dance, painting, performances,” reads the first line of the press release for GARVEY: SEX LOVE NURTURING FAMALAY. This single sentence encapsulates many key points of your practice, for instance sharing as opposed to the idea of a solitary genius creating things out of nowhere (the leitmotif underlying your recently co-curated show Artists I Steal From).1 Or the importance of provenance and traditions, and celebration as a means to awaken a community’s sense of belonging. Would you expand on these topics?

AB: I’m so grateful to the folks who have given me ways of seeing and being. I just want to celebrate them because life is hard and I think we should celebrate the folks in our lives more. I’m so grateful to all the folks who have taken the time to talk with me because they didn’t have to, but so many people have taken time to explain things I don’t understand. I’m grateful for the musicians who helped me know what a feeling feels like and to the painters who invented ways of seeing that in turn help me understand what’s happening inside of me.

CM: In your opinion, what do you think art can do in our current sociopolitical situation? Do you believe art carries a political agenda?

AB: Art is always political. Someone once told me that privilege is not being aware of yourself, so as man if I’m in a room with twenty men I wouldn’t necessarily be concerned, but a woman may feel differently. I think art that claims to not be political is like me in a room of men. I grew up in hip-hop and I saw how rappers like 2Pac and Ghostface Killah and Lil’ Kim gave voice to folks who were dismissed by society—black men who just came out of jail, women who weren’t allowed to own their sexuality. I saw how rap changed larger cultural conversations. I saw folks feel empowered because their experiences became voiced. In the Caribbean like everywhere else we are having conversations about LGBTQ issues. The creative director of the float I designed for Carnival UCOM openly supports the gay community. The musicians who performed on the float gave an energy to the masqueraders who were wearing Paul’s designs, and that gave an energy to the design I made. It all came together to open up space for anyone to be welcomed, and I think that’s why they won first place.

CM: As a child you grew up in the Caribbean, the birthplace of dub—a genre of electronic music that sprung out of reggae in the 1960s—which is all about copying and remixing. “Dubbing” literally meaning using previously recorded material, copying it, modifying it, and recording a new master mix. When you moved to Brooklyn at the age of eight, you found yourself immersed in the emerging hip-hop culture, and the rise of DJing. Do you recognize these musical influences and their creative methodologies as substantial in the unfolding of your artistic path?

AB: Yes, one of the best facts of my life that I grew up in the golden age of hip-hop with Nas, Notorious B.I.G. “Biggie,” Timbaland, Pharrell Williams, Dr. Dre, Kanye West, Jay Z, Missy Elliott, Busta Rhymes, Lil’ Kim, Snoop Dogg, all these innovators. During that era in hip-hop it was about how much you could throw at a song and still make it sound like your song, your voice. Pulling apart hip-hop has made me make better paintings because I look at all the things that made a classic hip-hop album and I wonder if my painting sits next to Nas’s “Life’s a Bitch” where you have AZ, this young energy, rapping like fuck it I’m young, I’m ready to blow it all, and then Nas who has a more mature young voice comes on the second verse and he is more pensive, and then Olu Dara, Nas’s father, comes in with the cornet and ends the song with an atmospheric vibe with no words—just an old man who is listening to the two younguns, maybe aware of his own energy. In the upstairs of Sadie’s show are these white paintings that let you be in your thoughts after the explosions of these scenes of colors, sex, and pregnancy downstairs and I wonder if they can be next to a great Basquiat, who was thinking about all these elements of his life—hip-hop, Haitian jazz, Rauschenberg, the Lower East Side, Madonna, et cetera, and putting it into painting. The show ends with this blue hibiscus painting that pulls together a lot of those elements.

CM: Most of your production is intertwined with and indivisible from your personal place—your history and past experiences, your family and community. Motifs from your Caribbean youth, the usage of certain colors, and the integration of craft practices inherited from your family (like sewing) open your art to nonhierarchical forms of expression.

AB: I think I experience is important and has value, by which I mean a way to understand how to be present. I live to try to learn more, to be more sensitive, to feel and be more aware, and then I get to paint it. I get to see what Louise Bourgeois is doing and what Fay-Ann Lyons is doing and then I get think through that and find a way to paint that. The paintings are telling a story of everything I experience and in that story that I’m putting out in the world, I’m responsible for how those voices are put out there. In a conversation everyone should be heard, but being heard isn’t about equal speaking time; it’s about responding to how each person’s words sit next to the last idea. We know that conversations can fail because maybe one or two people are speaking all the time. My hope is that I’m able to balance a lot of voices in the paintings.