Spring/Summer 2021

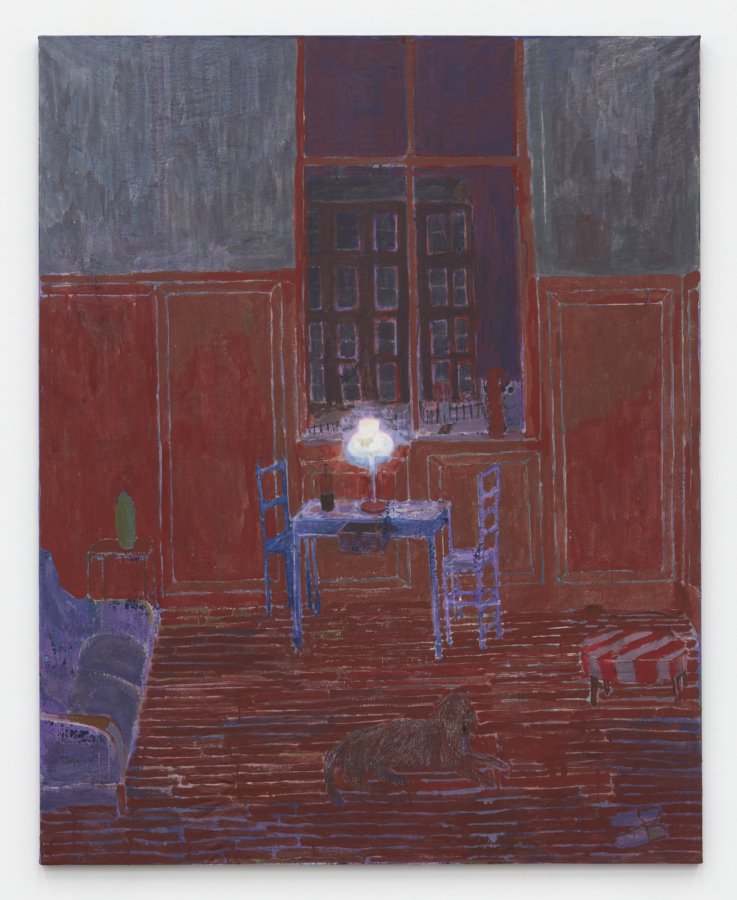

Andrew Cranston Moth 2021, rabbit-skin glue and pigment on canvas, 1790×1430mm, collection Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, purchased with funds provided by Alberto Fis.

In the latest of his ‘longer looks’ at individual artworks, Justin Paton is drawn into a room that’s warm with memory.

Somewhere are places where we have really been, dear spaces / Of our deeds and faces, scenes we remember /As unchanging because there we changed …

W.H. Auden’s lines are beautiful, evoking a poet’s life lived in transit. But perhaps we’re ‘really been’, in the past two years of lockdowns, have seemed unchanging in all the wrong, un-transformative ways. There’s that unmemorable window, that repetitive kettle, that predictable, endlessly recurring laptop.

Painter Andrew Cranston lived in a flat in Hillhead, Glasgow, from 2003 until 2020. He spent lockdown there, though I like to think that his painting Moth (2021) is not, or not only, about lockdown. Rather it’s about the warmth that accumulates in rooms that are inhabited generationally, which ‘bear witness’, as Cranston put it, ‘as if the experiences—painful and joyous—have been absorbed into the walls’. It’s about a kind of looking, both wise and childlike, that regards the ordinary and understands all the living held in it.

The painting is a rendered in dusky, plum-dark tones that at first make things hard to see. Even when your eyes have adjusted, there’s a sense of presences unseen. The mismatched chairs, so tall and attenuated, seem to stand for just-departed inhabitants, and the uncanny blue that defines their forms also makes them seem spectral, insubstantial. The stool, the couch, and the slippers also wait for someone to come and occupy them.

It’s a lived-in space that invites us, as viewers, to spend time inside it too. The partly opened drawer recalls Gaston Bachelard in his study The Poetics of Space, where he describes the potency of drawers, chests, and wardrobes as images of memory, privacy, and secret selfhood. The uncurtained window above offers a view of another kind of cabinet: the facing building whose many rooms must contain their own odd and ordinary stories.

The vastness of the window contributes to a feeling that the outside is looking in. Indeed, there are many points in the painting where something looks back at you.

The figure of a man standing on the pavement opposite adds, somewhat creepily, to this feeling, as do the dark dots that stare out like owl eyes from the ambiguous space beside him. (And now I’m looking at those dots again and seeing for the first time the tall vase that stands before them.) Then, more benignly, there’s the dog that Cranston has half-concealed in the patterns of the foreground, a shaggy presence (I love the scratched-in fur) who patiently waits for someone (artist, viewer, owner) to ‘come home’.

But the animating presence in this picture, the main ‘carrier’ of its theme, is the moth that gives the painting its title, and whose soft silhouette we can see against the glow of the lamp on the table. The moth, as a visitor from the night, reminds us of the vast world beyond the painting. Its tininess relative to the room makes this small domestic world feel enormous. And its ardent absorption in the light seems to say something about our attraction to this painting—how we’re drawn into a night-filled room where ordinary things have been made to glow.

Look, for instance, at the way Cranston treats the seams between things in this interior. The gaps between floorboards and the joins in the walls would appear as dark lines in reality. But in Cranston’s vision they’re openings that release the violet he has painted underneath. Recalling Leonard Cohen’s famous lyric about the ‘crack in everything’, which is ‘how the light gets in’, these glimpses suggest that there’s a stored energy leaking into this interior, unsettling it. They tell us it’s charged, that the space is dear; that the artist has really been here. But they also tell us that this charge is subjective and fleeting, which is why a painting is needed to hold it.

The effect is not unlike a photographic negative, where dark things appear light and vice versa. It also recalls heat-map imagery that reveals human warmth through colour. But Cranston’s medium is less hi-tech and his ambition is more enigmatic: to paint the heightened reality of those ordinary rooms that are always waiting for us in memory to re-enter them. In his words, ‘You live in spaces then they live in you.’