December 20, 2019

Download as PDF

View on rrealism

Art doesn’t imitate life, it instigates life. For the Painter Ann Craven — whose studio burned to the ground in 1999, taking an entire body of work along with it — the recreation of lost works is a means to go on working, making.

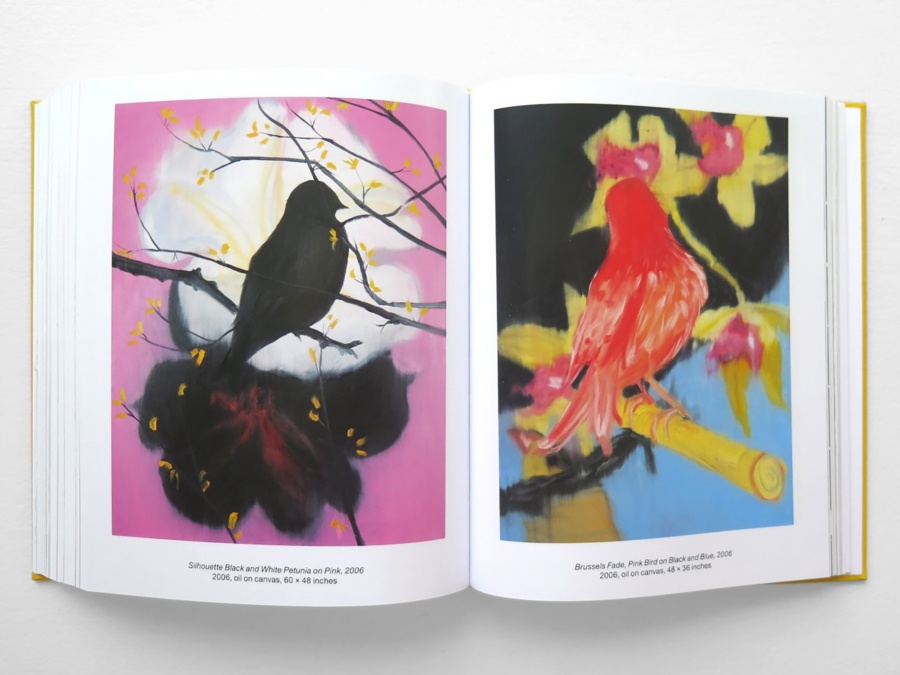

Craven’s work in oil is sometimes representational, depicting birds on branches and the moon in all its phases, or else it is abstract, in striped or palette pieces that pleasantly, surprisingly, contrast with those depictions. Despite their seeming verisimilitude, Craven’s paintings are not your average en plein air — though her many moon works are composed that way. Instead, each bird is an attempt at reanimating what once was, but which is now lost.

The 560-page monograph, Ann Craven (Karma, New York, 2018), reflects the painter’s process and resultant serial work — an arrangement or rearrangement of memory, from image to image. These pictures are tricky things. Their particolored aspect could be seen as decorations for a motel room wall. Nothing about them impresses at face value without an inkling of the kind of work it takes to paint them this way. Like Proust’s remembrances, Craven’s virtuosic, memory-engaged recreations of lost paintings show a fervent effort to transcend time through the creative act. All of the painted birds she has recreated from memory are an attempt at continuity during a time of relative fragmentation.

Ann Craven, Ann Craven, Karma, New York, 2018. 560 pages

The canaries, bluebirds, parrots, cardinals, et cetera look like what they were once painted after: a dusty old reference book that Craven found in her grandparents’ cellar. Yet given the story behind this series of paintings — thanks to the book’s lucid introduction by curator Dana Miller, “Ann Craven: The Nature of Memory” — their presence is a peculiar, exhilarating documentation of memory and the creative hand that engages imagination. In 1999, “a fire swept through Craven’s New York studio and laid waste to almost all of her existing work.” With this event, Craven’s oeuvre becomes a kind of archive that aims to lay hold of her world, the intermittence of life. Ann Craven documents a destroyed body of work that has been reinitiated, reimagined — painting by painting, “almost entirely from memory,” as Miller relates. After such a loss and resultant devastation, art can be a means to remember the past and make it new.

Through her practice, Craven examines and reexamines the slippery topic of what painting can do, relative to memory and reproduction, and also the ways in which memory fails. To quote the poet John Ashbery, “you cannot take it all in, certain details are hazy and the mind boggles. What till it all be like in fiver years’ time when you try to remember?” In addition to reproductions of paintings of varying size, the monograph also features many of Craven’s works in situ, in one of her studios. It is impressive to see Craven’s paintings standing up against her studio walls or on easels, especially the larger canvases. In this setting, the reader is made more aware of their individual aspect, that however copied the many repetitions of the same composition might seem, each thing has been labored over and rendered with skill, attention, protracted stretches of time. Here, the occupation with a single image or subject is jettisoned in the creation of something new, by way of new moments.

The fact that many of these paintings refer to the natural world — or rather, a kind of fond daydream of a memory of it — gives their repetition an air of strangeness. This is intensified by the birds’ indoor situations as well as Craven’s story. In this way, the animals may seem to have an air of symbolism, just as readily as the moon does, perhaps evoking harmony in lieu of isolation, confinement. The simplicity of Craven’s forms and these refined hues allow for a viewing experience that’s dynamic, not closed.

To appreciate Craven’s unique means and vision, plus the complexity behind her deceptively simple arrangements and forms, is to understand her body of work. In another essay at the beginning of Ann Craven, David Salle and Sarah French write that “The paint just lands; it’s not trying to prove, or be, anything other than itself. And it’s just this self-sufficiency that determines a pictorial world we can believe in. This believability, or the suspension of disbelief, has little to do with the what of the painting, but has everything to do with the how.” In spending time looking carefully through the book, one notices that nearly all of the bird reproductions are set against impressionistic backgrounds that bring depth to the representational conventions this particular series engages. Underscoring the boundary between figure and ground, they often look like two paintings in one, or like they were painted by two different painters, making terms like abstraction and representation seem silly, when really all paintings are, to some degree, abstract and representational.

The “1970s kitsch aesthetic that characterizes many of these selections conveys a reflexive nostalgia,” and it shows Craven’s deadpan humor, the mysteriousness in this body of work. Craven provides an answer to the question not only of what art should be “about,” but also how it is really not about anything. I consider aesthetic taste when looking at this book, because the subjects often come off as banal, almost seeming hokey ,while each picture as a whole stuns, gives reason to contemplate such things as how does the painter go about composing her scenes; why the moon; why the pastoral motif? Spending more time with this book, I find more about Craven’s renderings that baffle me, more that’s there and not there. The colorful spaces in the paintings do just as much as the identifiable forms. The most engaging pages of this book are, for me, the exquisitely impressionistic backgrounds — interludes in the book, where Craven blends palette with picture — or at least that is what it looks like.

With this kind of setup, subject matter doesn’t matter so much, so long as it engenders recollection of the original objects or the consideration of something new. Craven’s paintings register as totally contemplative — eschewing habit for perception, while reconciling the need for daily practice, refinement. They provoke, and are born of, the consideration of time and what can be carried over through its passage, the haze of perception, what changes, what might appear to stay the same. In the book’s second essay, painters David Salle and Sarah French argue, “each brush stroke contributes to a transmission of energy, from painter to paint, that makes a canvas come to life.” Each work’s color alone supports this claim.

Each of Craven’s many moon iterations clearly transmit this energy. This process of perceiving and documenting daily celestial phenomena is also shared on her Instagram feed, making the moon seem as wonderful as it is dumb: each of us is in awe of it every night is makes an appearance, yet aware of its heavy cliche. The paintings, however, take the documentation a few great leaps further. Craven’s Instagram snaps of the moon sometimes show up way pixelated, zoomed-in, amateur, there to document the moon’s station in the sky at that moment. In the feed, the pix are also titled: Untitled (Moon Phase, 03–14–19, 7:16PM, NYC), 2019, just as the paintings are. The images are then followed by an image of a painting that renders another phase, bringing out the grandeur and enigma of the moon in a generalized, impressionistic manner that breaks through the observer’s passive gaze — in some of the moon paintings, Craven’s handling is lush, full of the energy of movement, or else so thickly applied it looks like frosting for a cake. Craven’s moon isn’t the banal thing of treacly poetry; it’s this individualized, time-stamped occurrence that may as well be given a new, unfamiliar name. Similar to our perception of it, each of these takes is something distinct.

***

As Miller writes, “the deeply personal task of measuring time and preserving memory.” This measuring of time relates to the way that poets and artists are often occupied with dailiness as it relates to creativity — life as it is lived with the possibility of art. The work attempts to make something permanent of a moment. Craven’s paintings are brightly colored with recurrent motifs of canaries, parrots, moons, and there are pages that bear stripe-paintings and color palettes as finished compositions. The latter works are remarkable by contrast; these nonrepresentational pages are the liminal spaces of the book and they resonate with Miller’s chosen metaphor of music in her approach Craven’s paintings. These pages differ considerably from the rest of the book. In their sense of abandon and stylistic distinction, they clarify the rest of the work. The stripe- and palette pieces hone in on Craven’s eye for color and they signal a curiosity for discovery and process, being frank, open to showing how things function.

Ann Craven, Stripe (Avadavats, Lovebirds, Eastern Blues, at Sunset, on Snow, 2–17–18), 2018 2018, oil on canvas, KARMA

Using metaphor as a lens to look at this work, Miller likens Craven’s repetitions to music, specifically analogous to “cover songs.” Other takes have compared Craven paintings to repetitions in the work of Gertrude Stein, which was my first inclination too. But I’d like to avoid addressing these copies and re-imaginings as merely formal experiments or constraint-based exercises, so as to avoid minimizing the subjective complexity and depth in Craven’s work. I also think of Lydia Davis’s Almost No Memory, wherein the writer challenges the unending depths and shortcomings of memory. Davis takes her cues from the aforementioned Proust, whose In Search of Lost Time emerges from similar investigative places. For Davis, Proust, and Craven, the memory is a force and also a puncture. Davis writes in her title story’s opening line, “a certain woman had a very sharp consciousness but almost no memory.” That is a common predicament, but it is not only a subjective perspective, and a traumatic context, that makes Ann Craven interesting — Salle and French introduce the reader to ways of seeing Craven’s paintings: “paintings are being made, not merely puffy clouds of thought.” With a rarified imagistic intelligence, attention and painterly wherewithal, Craven reminds her audience that creative work can engage in ways that no other art form can.

Craven’s rumination of the past and its objects, her attention to the present, situates an ontological approach that confirms, among other things, the right to see, experience, and express the beauty and absurdity of the world. It’s the human attempt to engage in direct perception and expression that gives life meaning that’s otherwise often lost to the distractions of the everyday.