January 31, 2015

Download as PDF

View on Architectural Digest

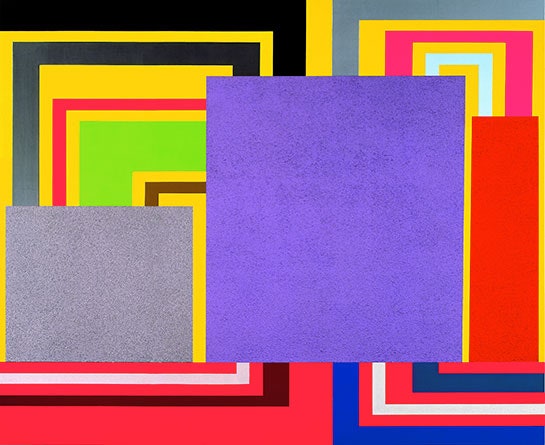

Cartoon Network, 1997.

For the famously brainy Peter Halley, abstract painting has long been far more than a means to experiment with form and color. For him, geometric abstraction is an opportunity to express something about the modern human condition. Since the 1980s, Halley’s trademark prison, cells, and conduit motifs have worked like simple diagrams of a complex world dominated by technology, for better or for worse. A new show opening today at the historic Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Connecticut, “Peter Halley: Big Paintings,” offers a rare opportunity to see how those instantly recognizable motifs have evolved over four decades via nine monumental canvases, some of Halley’s best, on loan from major museums.

Halley was invited to exhibit at the Griswold Museum—a former boardinghouse and art colony that became a hotbed of American Impressionism in the early 20th century—in part because the institution aims to showcase artists with a connection to Connecticut. (Halley studied painting at Yale, then later directed the school’s graduate painting and printmaking program for nine years, and he still lives in the state.) But Halley’s roots are in New York City, where he helped energize the 1980s art scene. In a game-changing challenge to much of the work coming out of the ’60s and ’70s, Halley brought recognizable imagery back into abstraction. “Even in 2015 there is an impulse to imagine that geometric abstraction just plays with ideas up in the clouds,” says the show’s curator, Benjamin Colman. “But these are so rooted in really complicated ideas that most of us face day to day.”

Halley often used dazzling synthetic colors and highly visceral industrial textures, and the show is a visual treat. But what stands out most is how relevant his work looks today. Halley’s paintings from the ’80s and ’90s were made long before computer and phone screens became omnipresent, and yet they engender that inevitable sense of both isolation and interconnectedness that dominates a digitally driven existence.

In his more recent work—including a sparkling new painting in the show called Accretion (2015)—Halley continues his subtle investigation of abstract imagery that invokes tech-driven culture, arranging his squares to convey a feeling of “encapsulation,” he says. “It’s a way of thinking about the fact that our culture is no longer looking out the window but enclosed in this technological universe.”