August 11, 2021

Download as PDF

View on Artnews

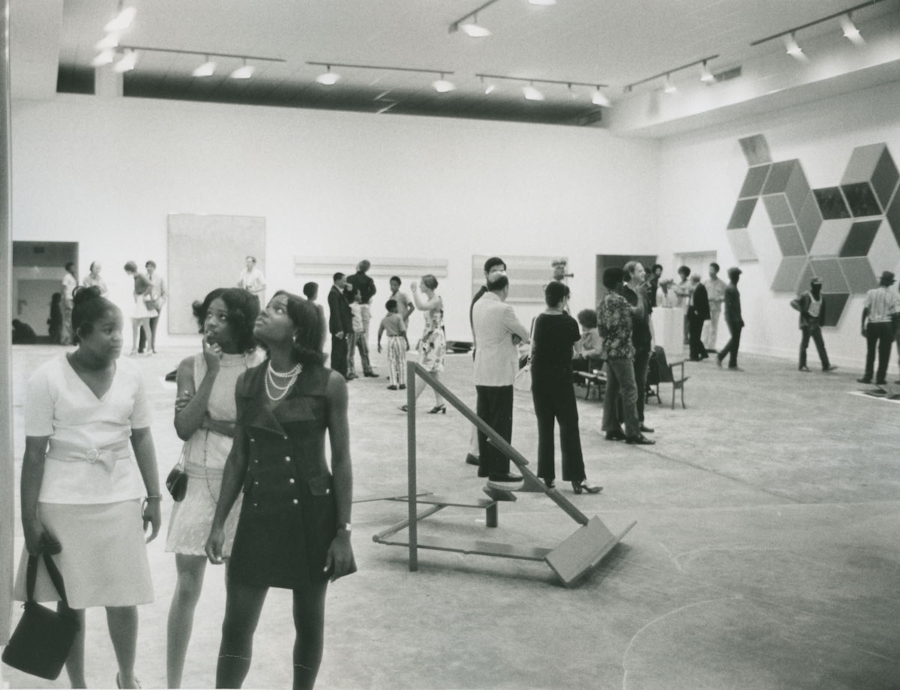

Attendees at “The De Luxe Show” in 1971. COURTESY MENIL ARCHIVES, MENIL COLLECTION, HOUSTON/PHOTO HICKEY-ROBERTSON

In July 1971, artist Peter Bradley wrote out to 18 artists seeking work for an exhibition due to take place in Houston, Texas. This wasn’t a typical summer group show, however—it had grander intentions. Anthony Caro, Sam Gilliam, Virginia Jaramillo, Al Loving, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, and Larry Poons were among those who received typewritten letters that started out with the following: “We’re planning an exhibition in the poor section of Houston. The object is to bring first-rate art to people who don’t usually attend shows. Hence our intention to rent a large space, a church, a ballroom, an empty warehouse. It will be of easy access to housewives, children, laborers; the people.”

By some accounts, the exhibition that resulted, “The De Luxe Show,” was the first racially integrated exhibition in the U.S. Today, that premise hardly seems provocative. But at the time, when protests led by Black artists against their exclusion from the U.S.’s top museums were mounting, it was a major step. As Bradley once put it, “This [artist] selection breaks down the barriers that create this whole theory of black shows and white shows.”

Presented 50 years ago this month, the exhibition took over a dilapidated movie theater in Houston’s Fifth Ward, a predominantly Black neighborhood. To toast its legacy in the present, a two-venue exhibition at Karma gallery in New York and Parker Gallery in Los Angeles opens on August 12. (Last year, to mark the show’s anniversary, the Menil Collection mounted a survey of Jaramillo, the only woman and Latina included in the exhibition.)

Lead-Up to the Show

“The De Luxe Show” was borne in part out of a center of the art world that was more than 1,600 miles away from the Fifth Ward. In New York, museums were being met with protests from Black artists and activists. “Harlem on My Mind,” a 1969 Metropolitan Museum of Art show organized by a white guest curator, Allon Schoener, generated fierce pushback because it did not include a single painting, sculpture, or drawing to tell the story of the storied New York neighborhood. Additionally, Schoener ignored the recommendations of Harlem community leaders whom he called on. The Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC), along with artists like Benny Andrews, Romare Bearden, and Norman Lewis, showed up to picket the show.

Around the same time, BECC began a series of heated discussions with leadership at the Whitney Museum that ultimately led to the institution organizing “Contemporary Black Art in America,” curated by Richard Doty. But the absence of a Black curator proved controversial, and Doty’s relationships with artists in the show soon soured. By the time the show closed in 1971, a whopping 24 of the 78 participants—among them Barbara Chase-Riboud, Joe Overstreet, and William T. Williams—had withdrawn their works either in the run-up to the exhibition or during its run.

In her 2016 book Mounting Frustration: The Art Museum in the Age of Black Power, art historian Susan E. Cahan writes that the debate surrounding the Whitney show “broke open a dialogue that laid bare the subjectivity of the museum’s voice, the impossibility of the neutral voice boldly and shamelessly claimed by those in positions of institutional authority.” Out of all this came “The De Luxe Show.”

What did Black artists want to see for themselves in an exhibition about contemporary art by Black artists? That was the question that John de Menil asked Bradley when he first contacted the artist about the prospect of the “The De Luxe Show.” In early 1971, John’s wife Dominique had invited artist Larry Rivers to organize the exhibition “Some American History,” whose subject was the violence inflicted upon Black Americans across the centuries and which included works by six Black artists, including Bradley, Ellsworth Ausby, Frank Bowling, Daniel LaRue Johnson, William T. Williams, and Joe Overstreet.

The response to “Some American History” was strong. Time critic Robert Hughes wrote of its potential to be considered as “propaganda, or history, or reality, or radical chic, or simply an art show”—but that its mere existence was proof enough that it was something important. “The De Luxe Show” was in part a way of rectifying some of the criticisms levied against “Some American History.” Of the 18 artists invited by Bradley, who was based in New York, just two—Chase-Riboud and David Diao—declined. The show wound up being staged in the De Luxe Theater, in an area that had once been home to a number of Black-owned businesses, at the behest of Houston community organizer Mickey Leland.

Peter Bradley’s Vision

“The De Luxe Show” assembled some of the era’s most cutting-edge artists in one space. Oval-shaped pieces by Ed Clark, made by pushing paint with a broom to create elegant smears, were shown beside an unstretched, spattered canvas by Gilliam that took on sculptural qualities. A stately green monochrome punctuated with three curvy lines by Jaramillo shared space with a hulking sculpture composed of industrial materials by Caro, then among the most celebrated artists in Britain. A monumental painting composed of adjacent cubes by Al Loving hung near paintings made via a spray gun by Jules Olitski.

This was a show with a very specific aesthetic. Bradley’s show was of a piece with the then-prevalent mentality that abstraction was simply better and more sophisticated than other styles of art-making, and that painting and sculpture were the prime mediums. It was also male-dominated, like many exhibitions of the era—just one woman (Jaramillo) made the final artist list.

Bradley designed the exhibition with the hope that the art on view would be legible to the masses. His primary audience, he said, was local children, especially under the age of 12. “The young kids are really the ones that get something out of it,” he said. Children also likely wouldn’t have know that the abstraction on view had in some ways been informed by lofty debates surrounding Abstract Expressionism and formalism. “This is all light and airy and free,” Bradley said.

Based on local reporting during the show’s run, the exhibition received a healthy stream of visitors. Critic Clement Greenberg, who played an integral role in defining Abstract Expressionism during the postwar era, attended the exhibition and later wrote, “When the neighborhood people started coming in, I became aware of something like a tingle of exhilaration in the air… People were really looking. They were taking the art seriously.” The Houston Post’s report on the exhibition claimed that it “demonstrated that there is a vast untapped reservoir of curiosity and human potential new experiences that is rarely piqued or reached by the conventional museum format.” Indeed, Bradley’s target demographic had been reached—as evidenced by a photograph of a school bus filled with Black children en route to the exhibition, some shown throwing up their fists in the air.

The children pictured were among the more than 5,000 people who saw “The De Luxe Show” in the course of its run. But not all visitors were pleased. The Houston Chronicle interviewed Vivian Ayers, a Black member of the Harris County Community Action Association. She told the publication, “Nobody I knew who went to the show was even able to describe what was there. To me it showed a curious absence of a sense of cultural relevance. Everybody knows the ghetto mood has changed over the last few years. The people know now why they wouldn’t necessarily have a feel for all the white man’s art they’ve been seeing.”

More recent studies of “The De Luxe Show” have also applied a critical lens. In his 2016 book 1971: A Year in the Life of Color, which features a lengthy chapter about the exhibition, art historian Darby English writes, “Bradley and his cohort did not merely court but rather invited such condemnations by launching their experiment when and where they did. But what work did the knowledge—the certainty that this was a risk worth taking—do?”

The show did succeed in bringing art that at the time would normally have been shown in a museum to the masses. (Now, some of that art might also be shown by a mega-gallery—Clark and Gilliam are represented by Hauser & Wirth and Pace, respectively.) And that “The De Luxe Show” came into being at all makes it special for its time. Speaking to William Middleton, the de Menils’ biographer, in 2004, Houston activist Delroyd Parker had nothing but praise for the exhibition, calling it “revolutionary.”