November 8, 2018

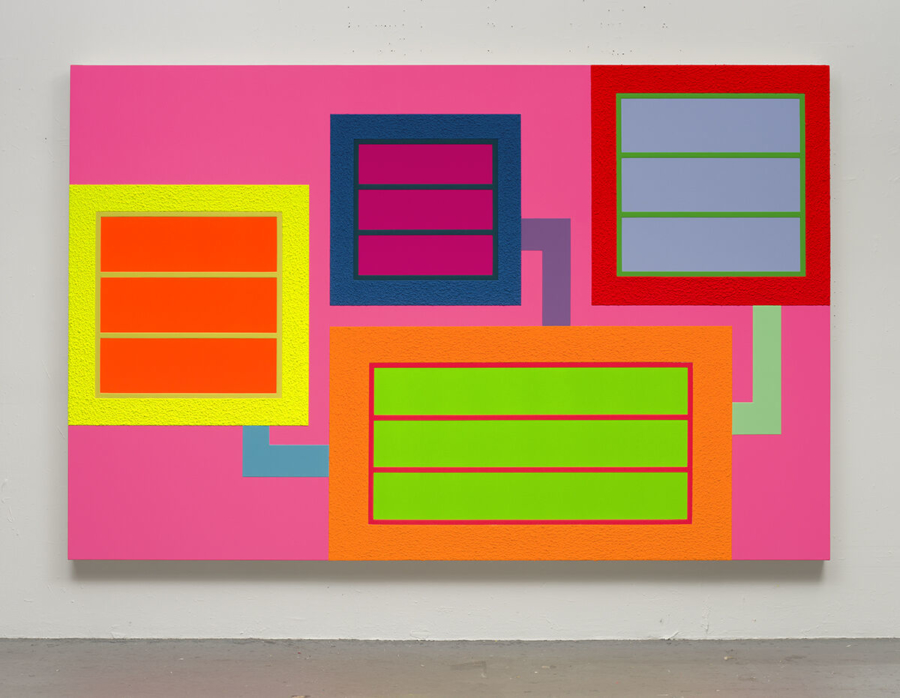

Peter Halley, Here and Now, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York.

In his light-filled Chelsea studio, sitting near a grid of windows overlooking the Hudson River, artist Peter Halley searches for images of his latest installation on Instagram. Instead of showing me professionally shot photographs, he flicks through strangers’ documentations of his exhibition at New York’s Lever House. The building—completed in 1952 by Gordon Bunshaft, with significant guidance from unsung architect Natalie de Blois—has hosted contemporary artists in its Art Collection such as Katherine Bernhardt, Damien Hirst, and Adam Pendleton since 2003.

Halley has created a maze-like interior within the building, and we tour it on his phone. Here are the fluorescent yellow walls that he and his team erected, upon which he’s hung his newest neon-hued, shaped paintings: adjacent rectangular canvases, sometimes arranged in a circle or L-shape, or mounted on top of one another. One chamber is black-lit and wallpapered with scans of his sketchbooks from the 1980s, while another features colored lights and wallpaper decorated with serial repetitions of a comic-book explosion motif. I ask Halley if he is opposed to Instagram, thinking the platform might cheapen the work or take away from the experience of viewing it in person. “To see how different people photograph it is really exciting for me,” he counters, supporting an app that he finds “enormously democratizing” within the context of the art world.

I probably shouldn’t be surprised: Halley’s work has long celebrated digital connection, especially in an isolating urban environment. The artist rose to prominence in the early 1980s, gaining acclaim for the unique iconography that’s defined his oeuvre ever since. He launched his career with paintings created not by brush or hand, but by rollers. They offer stark depictions of prisons (simply represented by solid squares with a barred window), cells (solid squares), and conduits (channels consisting of straight lines that bump against the other structures). An early effort, The Prison of History (1981), features a bleak vision: a single prison made of grey cinder blocks against a black background.

In a 1982 essay, Halley wrote that “the idealist square becomes the prison. Geometry is revealed as confinement.” In other words, the shapes reference not just architectural structures, but the limitations of modern art, as well. DayGlo hues became another trademark of his practice, in addition to the use of Roll-A-Tex, a popularly available sand texture additive used in house painting.

“The Roll-A-Tex had its origins in a kind of joke about materials,” he tells me. Using it, Halley rejects self-serious celebrations of the individual gesture and likens himself to a house painter. Indeed, he compares his studio to an architect’s office, filled with associates who are emerging artists themselves(current and former assistants include Lauren Clay, Nikki Maloof, and Ethan Greenbaum)—not the domain of some solitary genius. While Halley’s work can feel impersonal, a sense of human loneliness and restriction emanates from many of the cool early works.

Halley says that his breakthrough occurred around 1983, when he really began to feel a sense of connection via burgeoning technologies. More conduits appeared in his work, linking his cells. Throughout the ’90s, his paintings became busier and more vibrant, with more complex configurations. Connections between various shapes abound—the mood of Halley’s paintings seemed to shift from alienated to energetic.

Halley’s titles, too, reflect this evolution. In Cartoon Network (1997), for instance (even the name betrays a more lighthearted vision of the world), pink, green, brown, and gray conduits all link a silver-and-purple square, with the latter similarly attached to an orange rectangle. Halley cites the Memphis Group (which made bright, whimsical furniture) and its major figure, Ettore Sottsass, as inspirations; an element of fanciful design pervades Cartoon Network. Similarly, Joy Pop (1998) is a riot of pearlescent green, pink, orange, yellow, and navy, with conduits pulsing around the painting’s central cells. They appear to be mid-movement, like cars spinning on a carnival ride.

During the 1990s, of course, technology was making significant leaps toward ever-greater connection, with the public launch of the World Wide Web in 1993. “I [don’t want] to be a show off or anything,” Halley says, smiling, “but there are people who say my work anticipated this digital space.”

And Halley has, of course, kept abreast of more recent developments. His acceptance of Instagram neatly coincides with his interest in populist appeal. His work and his conversational patterns espouse both high and low culture. Throughout our discussion, he riffs on French New Wave film (Contempt, by Jean-Luc Godard, is a favorite; in his studio, he keeps a sculpture of Poseidon that’s a copy of one featured in the movie) and post-structuralist theory (he likens the philosophy of Michel Foucault to the artwork of Robert Morris). Yet he also compares the blacklight and flashing lights of his Lever House installation to the “cheap tricks” of a “fun house or state fair.” He’s riffed off the vernacular for years, particularly with an ongoing series of prints depicting comic book explosions. Halley wants to infuse levity into his formally rigorous presentations and avoid the “pretensions and seriousness” that plague the gallery world.

Halley’s career, both inside and outside of his studio practice, also reveals a keen interest in mass media and collaboration. He co-founded index Magazine, a compendium of cultural hipness, which was published from 1996 through 2005. Interviewees ranged from Eve to Ellen Gallagher and Morrissey to Jerry Hall, with photographers such as Wolfgang Tillmans, Tina Barney, and Catherine Opie supplying the visuals. “The key to running a magazine,” he tells me, making it sound quite simple, “is listening to people with different interests and points of view and putting them together in an interesting, fresh way.”

From 2002 to 2011, Halley served as the director of graduate studies in painting and printmaking at the Yale University School of Art. Teaching, according to him, was “a real addiction…a real high….It takes you outside yourself.” When he left, he turned to more intensive installations for such similar doses of excitement. He likens the thrill of mounting large-scale projects to “putting on a school play,” with various people taking on different roles, leading up to a climactic opening.

The Lever House commission, in some ways, offers a culmination of Halley’s ideas over the years, and celebrates his hometown—he grew up just blocks from the building. Indeed, the show itself is simply titled “New York, New York.” Lever House Art Collection curator Roya Sachs says that it’s Halley’s “love declaration” to this city, “that dream, hope, energy, and environment.”

The project is hardly Halley’s first multifaceted installation. In 2002, he wallpapered Chelsea’s Mary Boone Gallery with bright pink-and-green explosions reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s Flowers series. Another wall featured more delicately rendered blocks and explosions. Halley has also shared the spotlight with Italian designer Alessandro Mendini, who has occasionally created the wallpaper for various installations of Halley’s paintings (at Galleria Massimo Minini in Brescia, Italy; Mary Boone Gallery in New York; and the Cartier Foundation in Paris, France). In 2016—for a show curated by Max Hollein, the newly minted director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art—Halley installed a yellow film across the skylight of the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, which bathed the interior in gold light. Throughout the entry’s rotunda, he mounted prints of his explosions, which enveloped viewers in their extravagant comic world.

For a 2017 exhibition at Greene Naftali Gallery, Halley painted the walls a glaring yellow. Before even entering the main space, viewers wandered through a gold-lit entryway that, like the Schirn installation, featured mural-sized digital prints of explosions. (When I walked in, I feared that I’d accidentally entered a Chelsea hotel lobby, not an art gallery.) From the central space, viewers could walk into a smaller, black-painted room that featured an untitled 1978 artwork by Robert Morris: a large-scale sculpture made of comprised copper and funhouse mirrors—a final, disorienting moment in this unusual show.

Yet Halley doesn’t like the term “immersive” to describe his comprehensive presentations—the word, he thinks, is too related to spectacle. “It sounds like somebody drowning,” he jokes. In fact, Halley believes that, since around 1980, “almost every artist [has been] responding to the idea of spectacle.” From Jeff Koons’s giant balloon dogs to Barbara Kruger’s political banners, artists have had to choose how much to embrace—or subvert—grand gestures. And the issue has only become more complicated in the digital age, where “so much of what’s online is spectacular,” Halley says.

As a nice contrast to the expansive Lever House exhibition, Sperone Westwater (about three miles directly downtown) is celebrating an earlier moment in Halley’s career with a straightforward painting show. Until December 22nd, the gallery is exhibiting the artist’s rarely seen works created from 1997 through 2002. Throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s, Halley exhibited more heavily in Europe than in the United States. “Europeans are more inclined to be interested in conceptual painting and conceptually oriented geometric abstraction,” he says (French theory, too, has long informed his work). He’d shown with Gagosian from 1992–93 and decided “the new generation of large-scale galleries wasn’t for me,” he says. “It turned out to be too impersonal.” It took years to find another situation in New York that felt right.

One representative work at Sperone Westwater, Emulation (2002), nods to its influences in its title—the fire-engine red, tangerine, bright yellow, and deep blues seem pulled directly from one of Frank Stella’s most famous paintings, Hyena Stomp (1962). Via email, Angela Westwater praised Halley’s “distinctive visual lexicon and bold palette.” Her gallery partner, Gian Enzo Sperone, originally turned her onto the works’ “enduring relevance—the issues of connectivity it addresses seem uncannily prescient today,” she said.

While Halley’s work may indeed have foreshadowed 21st-century technology, he still has faith in more old-school methods and materials. The artist doesn’t believe that the digital realm, and its neverending trove of images, can ever truly replace good painting. “When you think of who people think of as great painters like Vincent van Gogh,” he says, “it’s really about the surface. The tactile feel of it.”