December 20, 2019

Download as PDF

View on The Brooklyn Rail

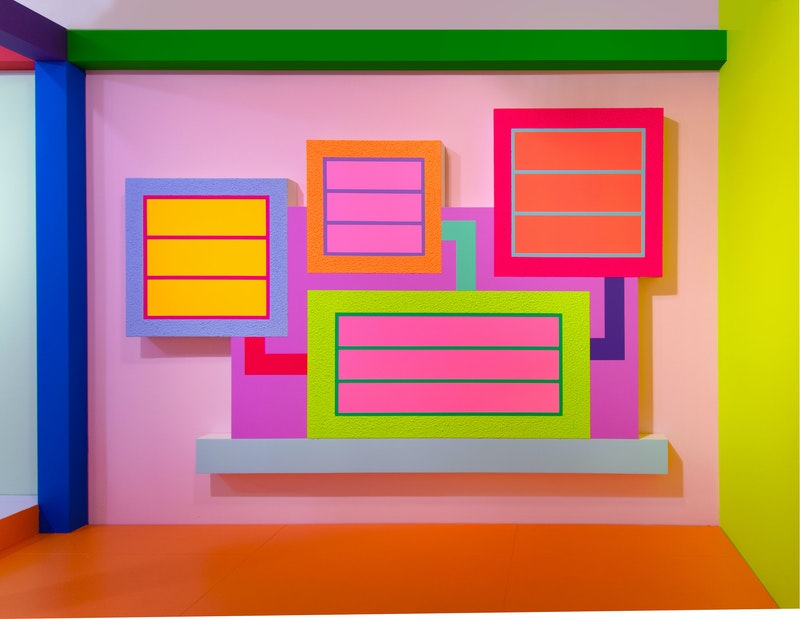

Installation view: Peter Halley: Heterotopia II, Greene Naftali, New York, 2019. Courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali, New York.

Fortress-like, Peter Halley’s newest exhibition, Heterotopia II (2019), immediately presents a situation of pleasure postponed. The bright, DayGlo green and yellow exterior walls of his temple-like structure offer only narrow slits and doorways through which to glimpse the throbbing color within. Ironically, with each passage into the next level, as we adjust to the increasing barrage of color and disorienting geometries, the artist pushes the limit of expectations higher, continually denying the satisfaction of a visual resolution to our quest. The artist is juggling so many questions with this piece, and other recent installations such as New York, New York (at Lever House in fall of 2018), that it is necessary to experience the work(s) first without listening to Halley and then doubling back to see if we buy his explanation. These beautiful funhouses offer jarring environments of color that massage the viewers’ involuntary responses by leading us through a series of visually hot and cold spaces as well as shimmering and glowing wall patterns and textures. As if that isn’t enough, we are then expected to soak up a series of Halley’s shaped canvas paintings. In the current exhibition, there are eight pieces, named after planets in Isaac Asimov’s sci-fi novels (no Trantor?), placed like altarpieces in chapels throughout the eight-room architectural folly that the artist has built within the gallery.

Beyond the formal, we must contend with the signs and symbols he juggles in his work—of cells, both biological and carceral; networks, digital and personal; historical progressions depicted abstractly; and color theory and its physio/psychological impact. Furthermore, Halley lays a heavy philosophical trip onto the viewer: the question of utopia versus heterotopia versus dystopia. There’s also the nagging question as to whether this is all just an elaborate ruse to exhibit paintings or a concerted effort to re-envision the idea of the gallery, museum or even the space we inhabit in general.

If you orbit Halley’s temple clockwise, you enter the structure through a long passage of sparkling tinsel cilia, and step into a buzzing green hall surmounted by the painting Terminus (all paintings 2019). Terminus is a lighthouse, a totem, and an altar all rolled into one and is perfectly matched to the gently rising space of the hall. While none of Halley’s paintings in the exhibition seems to have aspirations towards symmetry, as they present differently shaped rectangles and squares in opposition to each other, Terminus is markedly different in that its composition features progressively smaller forms placed one on top of another. As if pointedly to deny us the plebian satisfaction of relaxing our eyes on the vision of a symmetrical form, the pile of shapes in Terminus lilts to the left. The whole composition of the green hall is off-kilter—there is a screen of small apertures on the left-hand wall that gives a view into the core of the whole structure. But these rectangular perforations, like Terminus itself, while following a rectilinear matrix, are slightly off: maximum planning strategizing for a constant, nagging frustration. The movement through the entire structure of Heterotopia II concludes with a pair of rooms bisected by a row of four, rich blue columns; on one side is the painting Galaxia and on the other Hesperos. In Galaxia, a trio of smaller squares rise above a larger grounded rectangle, while in Hesperos a monumental square births a smaller square and an equally sized rectangle. All of these forms bear three horizontal bars that can be interpreted as windows, circuits, even faces. Or perhaps they are rough diagrams of spaces similar to the heterotopic series of rooms we are standing in? These two rooms lead us back into the green hallway, and we can leave or start again.

The general tenor of Heterotopia II is that all is slightly imbalanced, not so much in a way that feels wrong, but more that the whole installation appears designed with another species or varietal of being in mind. We are visitors to an alternate plane, and we aren’t quite right here. Flights of steps are too high, the colors make us uncomfortable: it’s like looking at the Navigator’s chair in Alien. The result is that Halley’s paintings seem like the only thing we can get a grip on; they are diagrams that play with, and indulge in, the idea of universally recognizable indeterminate signs. The entire structure revolves around a central core of greenish-yellow light that is viewed through an array of apertures: small rectangular punches à la Peter Eisenman (aggravating), a bisected circular window à la Louis Kahn (graceful), and a small balcony, from which we can see the simple “X” of lights on the floor that give the heart of the piece its magical hue. New York, New York presented Halley’s paintings on the exterior of the structure while the Holy of Holies on the interior was floor-to-ceiling glowing wallpaper with sparkling starbursts and black-lit miniscule rectangles. Here, the artist has integrated the paintings with the structure, and that works better. While we are never fully convinced that we aren’t in a gallery looking at art, we do find ourselves on a journey, or in a temple, and the paintings serve as both suitable decoration of this otherworldly sanctuary and impenetrable roadmaps and floorplans for that quest.