July—August 2021

Download as PDF

View on Brooklyn Rail

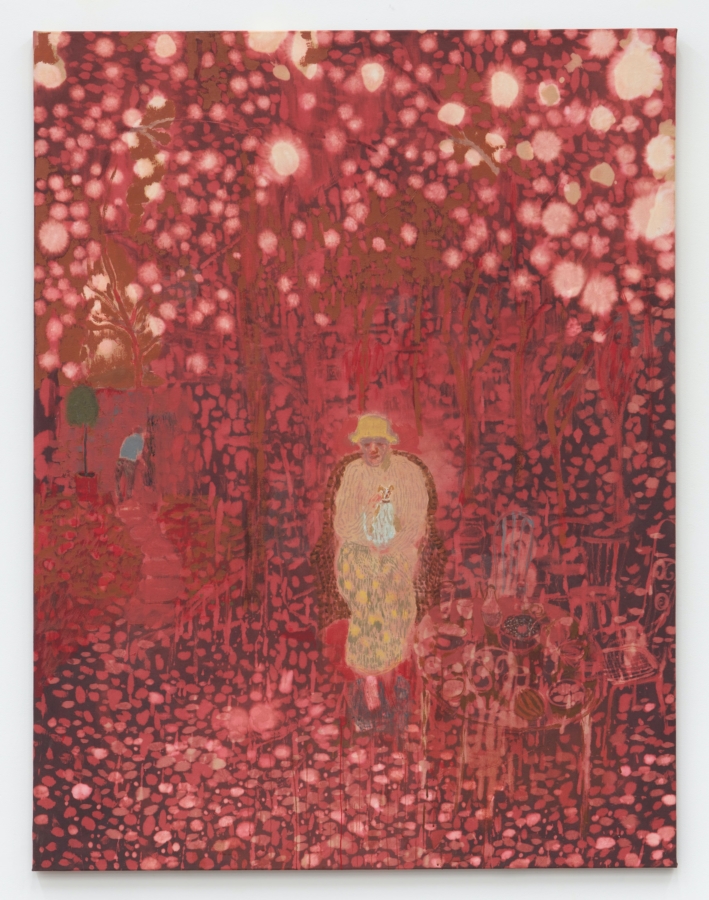

Andrew Cranston, Waiting for the Bell, 2021. Rabbit skin glue and pigment on bleached canvas, 66 7⁄8 × 51 1⁄8 inches. Courtesy the artist and Karma, New York.

Waiting for the Bell, Andrew Cranston’s first solo show in New York at Karma, presents a new direction in scale for his dreamlike and beautiful paintings. The show is split in two distinct sections: one contains many of Cranston’s small paintings on book covers, which he is known for; the other includes eight large-scale paintings on canvas. These are the standout works in the show. Each has a restrictive color palette and depicts simple, oddly familiar and sparsely populated landscapes. A sense of stillness prevails over everything.

In many of these works, Cranston has dyed and bleached the canvas, providing a light wash of color behind the subjects he paints. His compositions sit on top of these backgrounds, creating a compelling textural interplay and accentuating the physical qualities of the paint itself. The bowls and cups on the table in Waiting for the Bell (2021) have a physical presence. The bleach is cleverly deployed to create negative space or sources of light. The dye obscures the foreground-background relationship and perspective, all covered in a cloud of color, like Matisse’s Le’Atelier Rouge [The Red Studio] (1911). Cranston’s restrictive palette highlights the few moments of color that quietly call out: a green plant, a blue chair, a blue shirt, a yellow figure. The bold patterning of bleached light felt dizzying at first, but subtle details reward a long engagement. The show is full of marvelous technical craft, found in the texture of the swallowtail wood floors in Let’s talk about this story of yours (2021) contrasted with the texture of the figure’s dress; or similarly in the contrast of the texture of the dune grass, sand, and sea in It was your birthday (and a seagull shat on your head) (2021). This is all well balanced, never overwhelming, due to the textural void of the color wash behind each of Cranston’s scenes. There is an undeniably pleasant playfulness in his technique; it seduces you into the pensive atmosphere of his paintings.

Cranston’s large works provoke a universal melancholy nostalgia, but one that feels voyeuristic or borrowed. This beach scene in Cornwall 1979 (2021) feels familiar, but lost to time, recalling the Brazilian term saudade, or the acute presence of absence. The figures depicted don’t provide any psychological entry into the scene; instead, they feel more like anonymous pedestrians in dreams. And these are dreamlike settings, with grounded but ambiguous environments from a past the viewer has never known.

We are never granted much access to the subjects; we seldom get a full rendering of their faces, their feelings, who they are as people. The figures rarely hold any meaningful relation to one another, each figure existing in their own sealed and isolated headspace, recalling Balthus’s The Mountain (1937). Despite their lack of aesthetic similarity to Surrealism, these choices provoke a reaction in the viewer reminiscent of it; there is ample room for the viewer to fill in the gaps of meaning. Nowhere in this show is this more apparent than in Landscape with Rangers players (2021), a scene of soccer players gazing out at a beach before filing in procession up the dune hill. The figures lose their rendering into shadow as they ascend in sullen, almost Sisyphean posture. As in most of these paintings, it is difficult to say what time of day it is. The sky is presented in supernatural color, further disorienting the viewer and emphasizing the ambiguous and dreamlike quality.

The smaller works, of which there are many, occupy additional rooms in the gallery’s two sites. They are painted on hardback book covers; each could be held under one arm. The rougher texture of the underlying book covers is often visible in the surfaces of the paintings. Along with the oil paint, they contain varnish and rabbit skin glue, which accentuate the grittier impasto and muddy the image. These works have a more varied color palette and subject matter, with street scenes, domestic figures, pet portraits, and borderline abstracted still lifes. Overall, the smaller works are less cohesive than their larger counterparts. Cranston’s pictorial language is better suited to the larger, more contemplative canvases, but the smaller works still have the strong and engaging use of formal elements that define his painting.