April 1, 2017

Download as PDF

View on Artforum

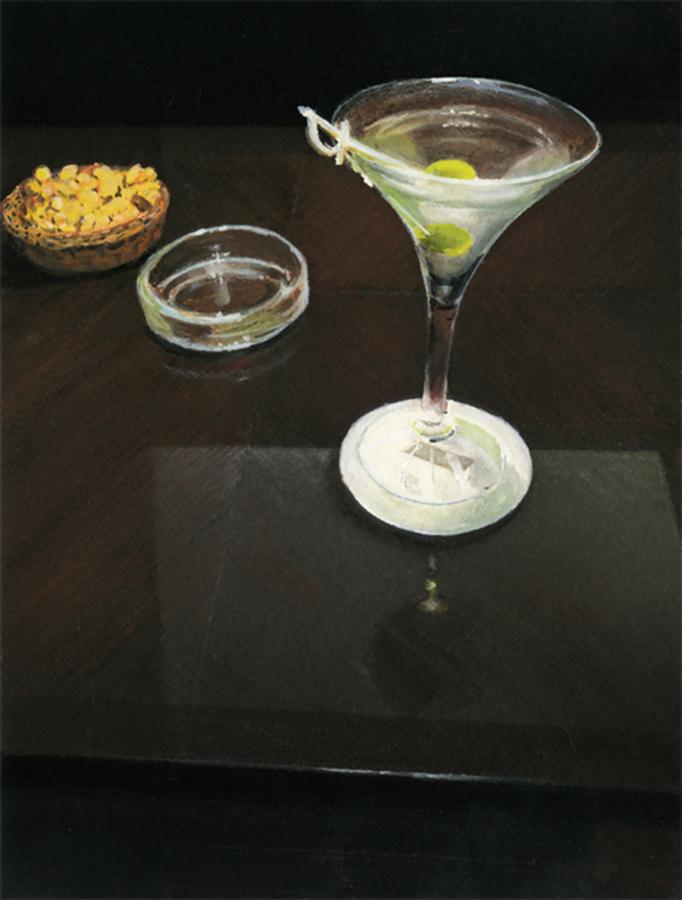

Dike Blair, Untitled (Kyoto), 2013, gouache and colored pencil on paper, 12 × 9″

For more than three decades, the American artist Dike Blair has dedicated himself to an increasingly rare kind of painting. It’s been overshadowed on the one hand by neo- and post-expressionist styles feigning an authenticity that doesn’t exist anymore, that’s no longer possible, and on the other hand by a post-Conceptual approach whose practitioners often act especially cool to cover up the fact that they don’t actually believe in their jaded view of their métier. Blair, by contrast, is all about painting, and about seeing. That may not sound exactly thrilling, and it’s taken critics a long time to take notice of his work. It has rarely been shown in galleries in Europe, so this exhibition of his gouaches and sculpture was a welcome opportunity.

Blair’s painting is undemonstrative and, more than anything else, sincere, although the artist himself has argued in an interview that sincerity isn’t a necessary ingredient for painting. After all, sincerity is typically opposed to illusion, while the latter has always been a crucial component of two-dimensional representation. What are we to make of this apparent contradiction? Blair’s gouaches show objects that are ordinary enough: doors and door handles, windows and windowpanes, light-filled hallways, cocktails in glasses, glass ashtrays. You can tell they’re painted from photographs, yet this isn’t photorealistic painting; light, in these pictures, doesn’t just aid in the physical conveyance of images—light in itself is the true subject of Blair’s work.

Take the gouache and colored pencil Untitled (Kyoto), 2013: See how the illumination lends a peculiar sheen to the surface of the glass holding a drink, how that sheen reflects the green of the olive in the clear liquid, how that reflection finds a distant echo in the translucent surface of a nearby glass ashtray. This rich accumulation of effects is much more than just a visual rendering of what the artist saw. Contemplating the painting, you almost feel the sensation of the cold drink hitting your tongue. The picture engenders an illusion that induces a physical reaction, and that’s what makes seeing more than a purely visual process. One is reminded of Vermeer, in whose paintings light is always more than merely an optical effect. A certain lightness, a sense of weightlessness, even a hint of eroticism are at the heart of the mystery inhabiting Vermeer’s pictures, despite their lucidity. And Blair’s art, like Vermeer’s, exudes a sense of solitude even in the absence of human subjects, additionally bringing the work of Edward Hopper to mind.

Besides the gouaches, this show included the sculpture OHCE, 2014, an ensemble of wooden art-shipping crates. At first glance, they seem entirely unrelated to the paintings. But some of their surfaces are painted, variously suggesting the sky or a landscape; a framed painting hangs from the back of each crate. With their austere geometric shapes, the crates resemble Donald Judd’s Minimalist objects, but unlike those objects, they’re never only what they seem at first sight. The painted surfaces lend them an illusionistic quality, something they share with the gouaches.

In another interview, Blair has spoken of a sense of mystery that emerges from his work. But what’s the source of that mystery? And, perhaps more important, what does it signify? The enigma is the fruit of an approach that employs a variety of means—most saliently, effects of light—to manufacture illusions, as in the painted cocktail glass. That’s where the ultimate sincerity of Blair’s pictures and installations lies: in demonstrating that seeing is never untinged by illusion.

— Noemi Smolik