March 25, 2021

Download as PDF

View on Artforum

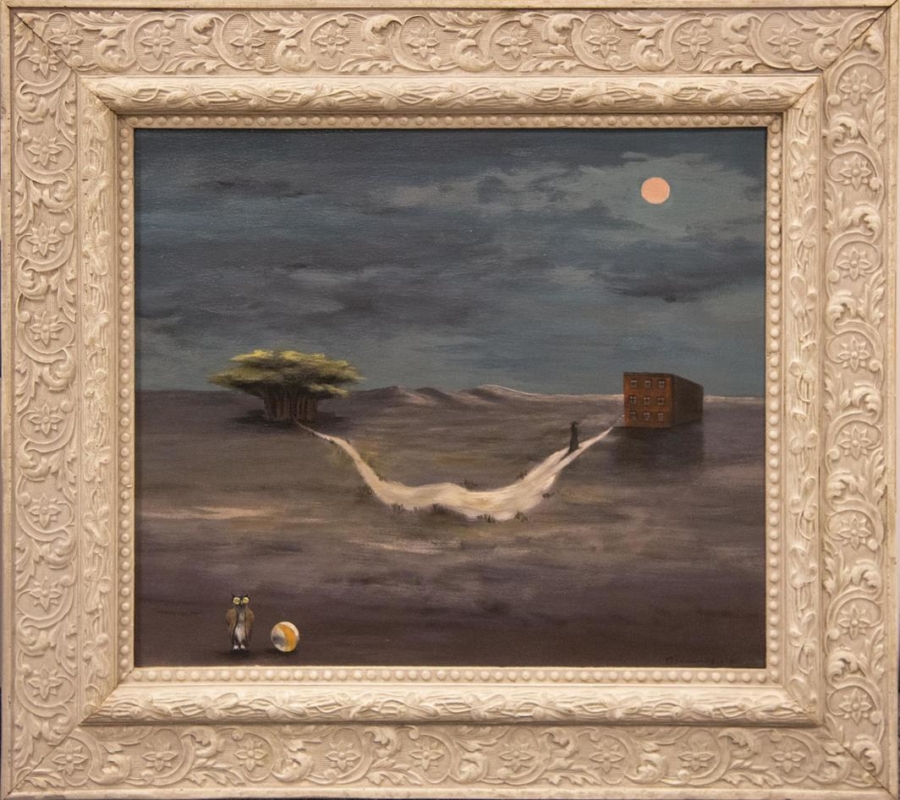

Gertrude Abercrombie, Deportation, 1948, oil on board, 16 × 18 3⁄4 inches.

The slipperiness characterizing many literary and art-critical terms is in particular evidence around the oxymoronic genre of “magic realism.” While its narrowest definition—the inclusion of the fantastical within an otherwise realistic setting—can be useful when applied to specific examples of fiction or art, the label is often employed in ways so elastic as to render it meaningless. Extra Ordinary: Magic, Mystery, and Imagination in American Realism, the exhibition catalogue for the show of that name on view through June 13 at the Georgia Museum of Art at the University of Georgia, aims to provide a more concrete understanding of this aesthetic as it coursed through American art from the mid-1930s to the early ’70s.

As Jeffrey Richmond-Moll, the show’s curator and the editor of this volume, notes in his introductory essay, magic realism has long confounded critics and viewers. German art historian Franz Roh introduced the coinage in 1925, and Alfred Barr borrowed it for the title of a 1943 show—“American Realists and Magic Realists”—at the Museum of Modern Art. His director of exhibitions, Monroe Wheeler, disliked the “precious, unfamiliar terminology” of the title, preferring instead the more commonly understood term Surrealism. But Barr sought to distinguish the work by artists such Andrew Wyeth, Edward Hopper, Patsy Santo, and John Atherton from Surrealism because of its “exact realistic technique,” which, he maintained, made “plausible and convincing their improbable, dreamlike or fantastic visions.” This emphasis on craft, on realism, clearly guided many of Richmond-Moll’s choices, although the selection includes imagery that could as easily fall under the Surrealist banner or no category at all.

Charles Patterson’s Peppers, 1953, presents a pair of gigantic green peppers against an unnaturally manicured landscape. Textured with a kind of tense muscularity, the fruits convey the sense they might burst forth from the board and, as such, are more than a little bit threatening. This slightly off-kilter depiction of quotidian objects, rendered with painterly exactitude, seems precisely to fit Barr’s characterization. But in another piece of Patterson’s—The Room, 1958—the stagey improbability and expressionless faces of its five assembled characters combine to much less disconcerting effect. A wide-eyed female figure reclines on a divan while a man and woman struggle with a large dog that may wish to chase the cat dashing beneath the studio couch. An open curtain behind the group reveals an elderly woman robing a skeletal figure in a bath. If the realm of unconscious reverie is being evoked, it is done with a deliberateness that recalls the clichés of an overly earnest Surrealism—locomotives emerging from fireplaces, elephants on bony stilts, and the like.

Elsewhere, a seductive degree of ordinariness compels our attention and allows the enigmatic, the unreal, to gradually emerge. On a quick glance, Z. Vanessa Helder’s pastel watercolor Pettit Carriage House, 1942, appears to be a typical picture of rural life. The agreeable soft colors and sharp, decisive lines suggest the orderly composition of an architectural rendering. But upon further reflection, the atmosphere grows ominous—the surrounding trees, bare and gnarled, appear to clutch at the structure; the carriage house itself, owing to a pair of oculus windows set above a dark open door, conjure an openmouthed countenance. The painting, as described by Richmond-Moll, “pulses with a disquieting supernatural energy.”

Artists that tread close to, and even step gingerly across, the line separating the outright fanciful from the plausible provide the surest warrant for the show’s moniker. In Shells and Figure, 1940, Paul Cadmus allows us to behold a male nude on the beach through a broken seashell that has been foreshortened to appear close and consequently enormous. The viewer occupies the position of someone lying prone on the sand, somehow hidden by the mollusk and thus able to spy on the young man (his full nakedness, crucially, obscured by the shell’s curve). Both the viewer and the viewed are contained within this aperture. The distortion of scale, the young man’s encirclement, and the strong voyeuristic element charge the otherwise placid scene—an aqua-blue sky, the undulating sand—with unnerving estrangement.

Indeed, what we call magic in many of these works is really more an almost lurid melancholy—a profound sensation of aloneness. In Gertrude Abercrombie’s Deportation, 1948, a tiny figure makes her way across a desolate landscape, her journey marked by a wavering white path between a tree and a building situated just below a full moon. In the lower left corner of the image, an owl, one of the artist’s favorite symbols, peers at us. Abercrombie, the accompanying texts informs us, claimed all of her work was autobiographical; the analysis suggests the painting’s origins in her own divorce or, perhaps, in the passage of the Displaced Persons Act in the year of its composition. Either or both events may have influenced the eerie tableau. But the voyage of a sole and spectral figure—no more than a slash of black paint—in moonlit darkness is one that is achingly familiar. What Abercrombie imagines is not so much the fantastic as it is the solitary, mundane transit we feel ourselves undertaking daily.