December 7, 2020

Download as PDF

View on ARTnews

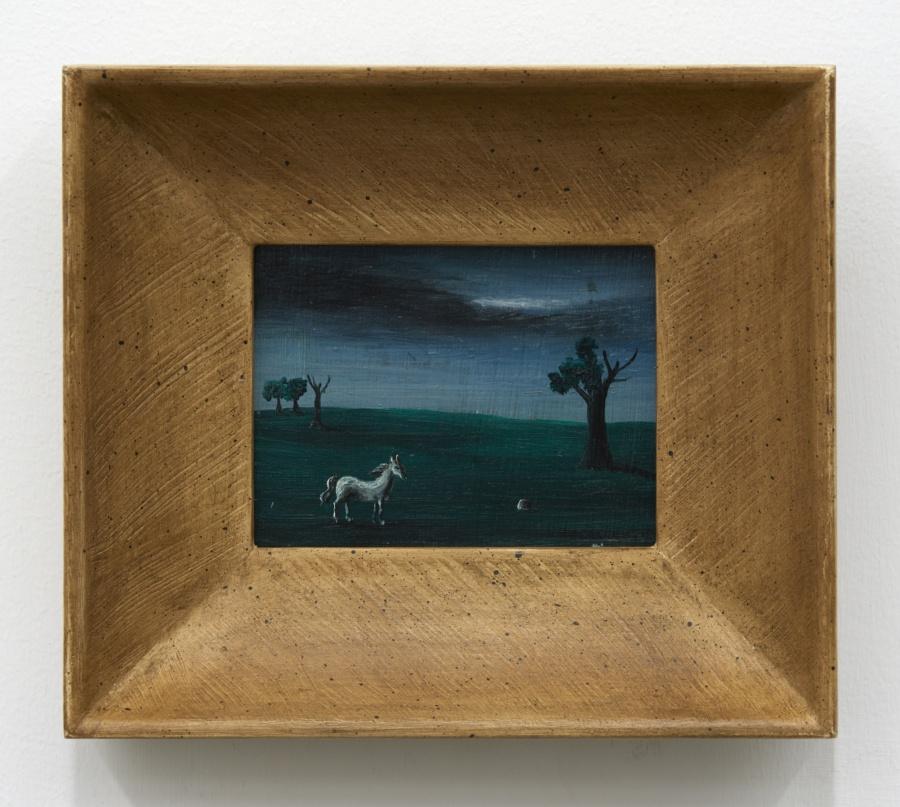

During the first half of 20th century, the American surrealist Gertrude Abercrombie achieved acclaim in Chicago’s art scene, but it wasn’t until recently that her fame extended beyond the city. Following a widely praised solo outing at Karma in New York in 2018, Abercrombie’s intimately scaled works depicting solitary figures, glowing moons, intricate shells, dreamy landscapes, and other subjects of personal significance to her have cropped up in art fairs and exhibitions around the world. Her paintings can be found in the collections of the Whitney Museum in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Milwaukee Art Museum, and other institutions. Ahead of a retrospective set to appear at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art in 2021, below is a guide that traces some of the key events in the artist’s life and career, from her early gigs working as a commercial artist to her showings at Chicago’s most august art institutions.

Abercrombie was the only child of opera singers.

Abercrombie was born in Austin, Texas, in 1909 to parents who worked as singers with a traveling opera company. Her family moved to Berlin in 1913, but when World War I broke out in Europe, they had to return to the United States. They went to live with her father’s family in Alledo, Illinois, before settling in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood, where Abercrombie would put down roots for the rest of her life. She

graduated from the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign in 1929 with a degree in romance languages and did a stint at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago studying figure drawing. She also spent a year studying commercial art at Chicago’s American Academy of Art, a course that would inform the trajectory of the first years of her career as an artist.

The artist was employed by department stores and the Works Progress Administration early in her career.

Abercrombie’s first job involved drawing gloves for Mesirow Department Store ads and she subsequently was employed as an artist for Sears. She began pursuing painting more intensely in 1932, and in 1933 she showed a selection of her idiosyncratic self-portraits and paintings of ladders, shells, trees, moons, cats, owls, and more at the Grant Park Outdoor Art Fair in Chicago. By 1934, Abercrombie was working as a painter with the WPA Federal Art Project, a post she would hold until 1940. The mid-1930s brought a fair amount of exposure for the artist, who in that period exhibited her work in group exhibitions at the Chicago Society of Artists, Katharine Kuh Gallery in Chicago, the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, and other venues.

Abercrombie’s landmark presentations in the 1940s propel her to fame in the Windy City.

In 1944, the artist got a solo exhibition with the Art Institute of Chicago, and her work also figured in the institution’s 55th Annual Exhibition of American Painting and Sculpture that year. She exhibited paintings in a group show at the University of Chicago’s Renaissance Society in 1945, and in 1948 she had a solo show at the Chicago Public Library. One of the works Abercrombie created during this period, titled The Visit (1944), depicts a characteristically eery, mysterious scene. The painting shows two figures—a woman peering out a window and a man peering in—encountering one another on a gloomy night. The Visit exemplifies Abercrombie’s penchant for exploring interstitial moments that defy easy analysis. Abercrombie kept a journal of events and interactions from her daily life, and her paintings might be seen as a reflection of the artist’s interest in her own interiority. She once said, “It is always myself that I paint.”

As her star ascends, the artist becomes associated with major figures in the city’s music and literary scenes.

Having garnered fame and notoriety in Chicago’s art world, Abercrombie nurtured relationships with jazz musicians like Sonny Rollins, Dizzy Gillespie, and Sarah sVaughan; writers like Thomas Wilder and James Purdy; curator Don Baum; and others. (Baum would organize a 1977 retrospective of Abercrombie’s work at the Hyde Park Art Center.) Dubbed “the queen of the bohemian artists” and “the other Gertrude” (next to the poet Gertrude Stein), she regularly hosted gatherings for Chicago creatives in her apartment. Following her 1948 divorce from her first husband Robert Livingston, a lawyer she had married in 1940, Abercrombie married the music critic Frank Sandiford, who introduced her to a number of the musicians she befriended. (She and Sandiford would split up in 1964.)

Abercrombie receives a number of solo exhibitions in the 1950s before her health declines.

Throughout the 1950s, Abercrombie had a series of solo presentations at galleries in the Midwest and eastern United States. Among the enterprises that showed her work during that period were Bresler Gallery in Milwaukee, the Newman Brown Gallery and Illinois Design Center in Chicago, and Edwin Hewitt Gallery in New York. Early in the decade she painted the work Countess Nerona #3 (1951), which depicts a lone woman reclining on a green day bed as she gestures at a stoic white cat before her. Later in the 1950s, she created Untitled (1959), which conveys a similar sense of solitude and shows a woman and a feline in the shadow of a house. It was during this time that the artist’s health began to decline, in part as a result of her alcoholism.

Interest in the artist’s eccentric works resurges many years after her death.

Abercrombie died in 1977 after her retrospective at the Hyde Park Art Center had opened. While her work was sporadically shown during the 1980s and 1990s, it was not until Abercrombie’s 2018 solo show at Karma gallery in New York that her fame grew more widespread in the U.S. Critic Roberta Smith wrote that the Karma exhibition, which marked the first showing of Abercrombie’s work in New York since 1952 and was accompanied by a hefty publication, afforded the artist “a new visibility that should be coaxed into an even greater fullness.” In recent years Abercrombie’s work has also figured in presentations at the Arts Club of Chicago, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, the Whitney Museum in New York, and elsewhere. The 2021 retrospective at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, which is curated by the museum’s director Eric Crosby and titled “Moored to the Moon,” is sure to contribute to growing fascination and demand for Abercrombie’s singular oeuvre.