December 10, 2020

Download as PDF

View on Art in America

Blue Umbrella, 2020, oil on canvas, 51¼ × 63¾ inches; 130 × 162 cm

At a time when events seem to accumulate rather than unfold, when news is always breaking, and boredom alleviated with the tap of a finger, it is hard not to appreciate the slow and absorbing canvases of Henni Alftan. In the nineteen paintings on view in Alftan’s first US solo show, held in both of Karma’s Lower East Side spaces, the Finnish-born painter, based in Paris since the late 1990s, lavishes attention on transitional moments, elevating emotions that are rarely romanticized, like expectation and monotony. Blue Umbrella (2020), showing a figure waiting alone on a street corner in the rain, pays homage to anticipation; Morning Sun (2020), to idleness, capturing the languid beauty of sunlight spilling across a living room floor. Classroom (2020), a depiction of an enlarged wall clock painted from below, places the viewer into the diminutive perspective of desk-bound child, offering an all too vivid reminder of the itching frustration of waiting for the school bell’s chime.

Alftan’s work is often described as cinematic, and rightly so. For all their banality and sense of irresolution, her paintings can feel like narrative shards, as if they were scenes clipped from larger film reels, the moments right before the plot takes off. As novelist Hermione Hoby puts it in the exhibition catalogue, Alftan leaves you with a longing to know “what happens next and what might be outside the frame.” Her images seem to be telling a story, but the meanings are inscrutable, and any sense of climax or conclusion out of reach.

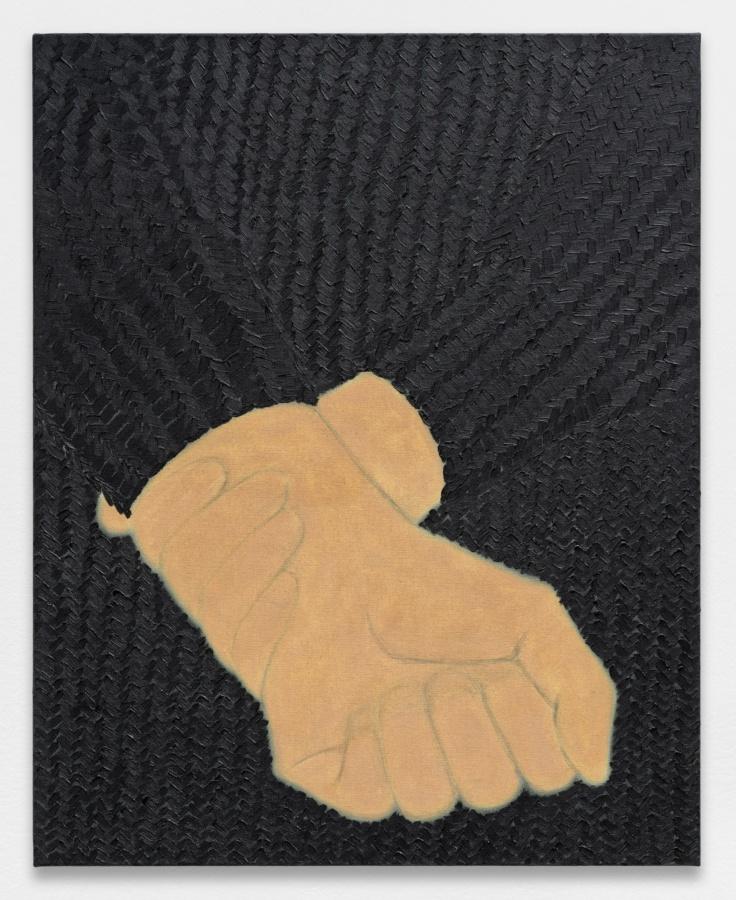

Hands Behind his Back, 2019, oil on canvas, 31⅞ × 25½ inches; 81 × 65 cm

This impression of unknowability is heightened by Alftan’s flat style of figuration and claustrophobic composition. She gives most of her painterly energy over to capturing textures (the soft down of a fur jacket, the bristle of uncut grass), leaving human flesh comparatively unmodeled—a choice that grants her subjects an immaterial, ephemeral presence. She also favors tight framing, opting to crop and compress views to provide only a sliver of the action. For instance, Hands Behind his Back (2019), a close-up of clenched hands, depicts a gesture of anxiety but gives no clue as to its source. In a similar manner, Body (2020) reveals just a slice of its protagonist, showing a torso outfitted in a sheer party top, bra visible beneath crossed arms. Is this woman on her way in or out? Expressing anger or modesty?

Alftan is at her best when she leaves such questions unanswered and less effective when she flirts with legibility, as in The Studio, 2020, a portrait of an artist’s studio that contains an abstracted version of The Jacket (2020), a work shown in the previous room. This easter egg of continuity gives the viewer license to imagine a story—The Jacket part of a larger autobiographical tale—and seemed out of place in body of work so intent on delaying gratification, so against gamifying the process of looking. Alftan is also less effective when legibility is foisted upon her. The most dissatisfying point of the show—the lone curatorial misstep in an otherwise superb debut—came with Haircut (Déjà-Vu), 2020, an example of Alftan’s “déjà vu” diptychs, comprising complementary panels meant to be hung separately. A clever conceit, the effect was ruined by the placement of the paintings in adjacent rooms, too close to foster any real sense of déjà vu or hold the viewer in a state of suspense. The high tension of the first panel, showing a pair of gleaming scissors open around a mass of long blond hair, dissipated the moment its companion came into view. The fateful snip was now accomplished, our need for closure too easily satisfied.