October 1, 2012

Download as PDF

View on Brooklyn Rail

Sharon Butler sat down with Louise Fishman in her cozy 23rd Street apartment to discuss her two current exhibitions: Five Decades, a 50-year retrospective at Tilton Gallery (September 5 – October 13), and Louise Fishman, at Cheim & Read (September 13 – October 27). She will also show with her mother Gertrude Fisher-Fishman and aunt Razel Kapustin at the Woodmere Art Museum in Philadelphia (Generations, October 13, 2012 – Janury 6, 2013). Fishman talked fervently about her recent residency in Venice, her new wife Ingrid, and how her experiences have shaped her work.

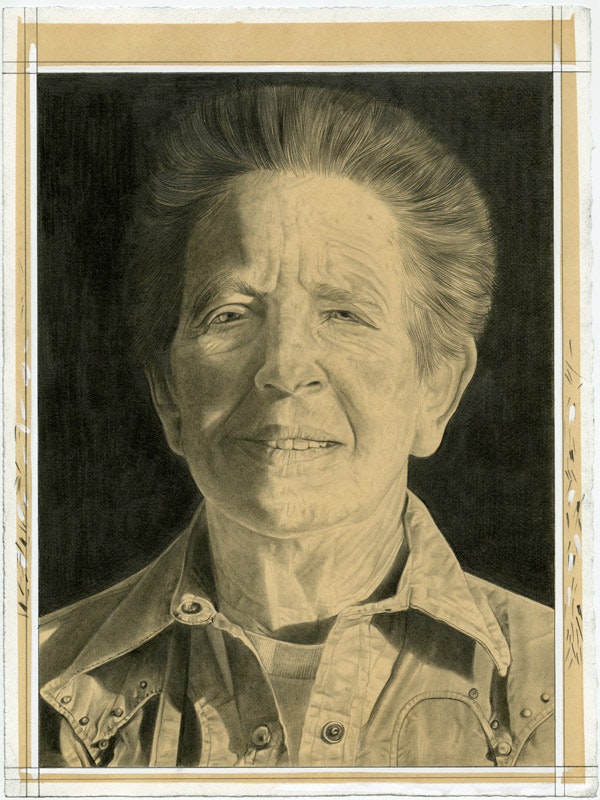

Portrait of the Artist. Pencil on paper by Phong Bui.

Sharon Butler (Rail): Let’s start by talking about your new work at Cheim & Read. I was knocked out by the color—especially the vibrant blues. Your fall 2011 residency at the Emily Harvey Foundation in Venice seems to have had a potent effect on your use of color.

Louise Fishman: Oh, big time. Blue has followed me for a very long time. A while ago, I was looking at a painting I made when I was an undergraduate sometime in the ’50s, maybe even ’60; it was the first abstract painting that I actually finished. It was full of blues and in a way it was like Picasso’s blue period, which I certainly looked at a lot. I didn’t really care for it as much as I cared for his later work, the Cubist and Surrealist stuff—I thought it was a youthful expression. I’m not sure what blue is, in terms of color theory; they’ve done so many color studies. For me it was water and sky . But the blue now is so deliberate. I didn’t say, oh I’m going to use blue because Venice is surrounded by water, or because the sky reflects in the water and on the buildings, or that the Titians are full of blue, or the city is full of these blues. I’ve known Ingrid for a very long time, because I knew writer and critic Jill Johnston, her spouse of 30 years, since the late 1960s. But one of the things I never noticed until Jill died and I went to various memorials and events that Ingrid had organized was that Ingrid’s eyes are this Danish blue. I was really struck by that. I mean you do look in your lover’s eyes, right? Plus, I bought this vase in Murano that is actually iridescent. This blue, which later appeared in my paintings, was all over the shops in Venice and Murano, including the Glass Museum. I got very involved in Venetian glass and still am.

Rail: Those vivid colors mystified painters for centuries. In our country, colonial painters doggedly tried to recreate the Venetian artists’ paint recipes, but they couldn’t figure out how they did it. For you blue has specific meaning and has become talismanic—that Ingrid’s eyes were blue was a signal.

Fishman: Yes. I’m in my early 70s, and I do think about my mortality: how much time do I have left to paint, what am I going to look at, what do I want to do with my time to make it rich and continue to make it rich? So all of those things take on a poignancy that I think, as a young person, I may not have had—I may have noticed her blue eyes, but I don’t think I would have integrated it the way I have. While living in Venice, I did a series of watercolor books, Japanese books that fold out, as well as regular drawing books. Plus I did drawings and watercolors every single day. And I took thousands of photographs. It was all interconnected. I’ve used watercolor before but not extensively like this. They were just spread out on a table and I deliberately kept everything left open, out, and ready. It’s unusual, because I’d never before worked like that. I would walk right over, pick up some tool and immediately make paintings. It felt like the veins were open and everything was pouring in and pouring out. I couldn’t work on larger paintings there. There wasn’t a proper studio. I didn’t want to be involved in sending stretchers and canvases to Venice and back to New York City. But I was constantly at work. It was like a stream of things all the time. Being by the water and staring at the water. Walking Sammy Sosa, my little rescue poodle, or waiting for a vaporetto, and watching the water change as the boats went by. And looking at the sky and taking in the reflections and light that emanates, the air actually feels like it’s colored there. And the reflections on all the buildings! So in terms of color—even the buildings have their own coloration, which is very rich. And I think it ended up in the paintings in a variety of ways. A lot of phthalos and ultramarines, and there are a couple of other colors that I introduced recently, I can’t even think what they are. I used to use a lot of Prussian blue and I sort of started eliminating that. I still use it occasionally. Because Cezanne used it, so of course I wanted to use it. But it would poison everything.

Rail: The sense of space is also completely different in your new work. In the older paintings at Jack Tilton, the shapes are very close to the surface with grids—more of a Hans Hofmann push-pull sense of space. But then, in this new body of work, the images are so dynamic. The shapes and space are bursting, exploding!

Fishman: That was starting to happen before I went to Venice. I was looking at books about Venice and Venetian paintings because I was supposed to go for four years in a row, but my father continued to decline, and I was afraid to leave. I was preparing for Venice for several years in a way.

I see a theatricality in the new paintings, which comes from a number of things, for example, the grandness of opera. There’s, of course, an operatic tradition of painting; the works in San Rocco and many other scuolas and churches have this drama, and it’s like theater. So there’s a rising, celestial grandness in all these paintings. I’ve always loved Titian and Tintoretto, but I tended to like the Titians that were much more reserved like the ones I saw at the National Gallery in London and the Prado in Madrid, particularly “The Deposition,” and also the “Pieta.” I thought those paintings were the most sublime. But being in Venice, I became involved in a whole other layer of his work as well as the work of Giorgione, Tintoretto, Veronese.

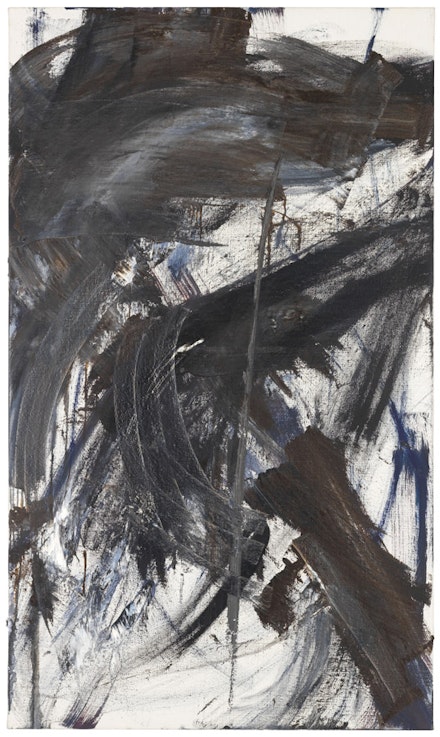

Louise Fishman, “Calle dei Cinque,” 2012. Oil on jute. 51 × 30”. Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York.

Rail: When you say sublime, what do you mean? Besides the theatricality, are you talking about the composition, the color, the content, the spiritual message, or all of those things combined?

Fishman: It’s hard to use the right words here, but I felt there was a spirituality and humanness, a humane-ness, a compassion, a connection with paint that was about compassion. His late paintings particularly have inspired me for most of my life. The quality of the mark and the light and the intensity of the feeling—they are so rich in the passion of paint. It’s not explosive, it’s not theatrical. When I went to Venice I was confronted with the quality of the elevation, so different from how I saw Titian before. It’s hard to miss the color, the richness in his paintings, and a lot of those reds. My use of red originally came from the Soutines I saw in Philadelphia as well as the van der Weyden crucifixion diptych with those two vertical red drapes. That was my early passion and it’s where I learned how to paint, in a way. The key artists for me, from the time I was an art student, were Mondrian, Cézanne, Soutine, and Rouault. When I finally got into the Barnes Foundation at the time it opened to the public, I could not get away from those Soutines. Barnes bought his whole studio out. And many of them are on view. I studied them, particularly the Céret period—those landscapes, that red! I think that red in my paintings has something to do with being a Jew.

Rail: In your newer work, since, say the 1990s, you’ve created specific series. I can imagine that each of the paintings at Tilton was part of a larger group, and I’m interested in how you move from one series to the next.

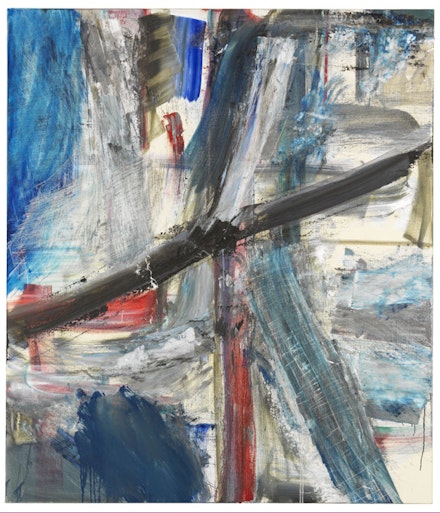

Louise Fishman, “Assunta,” 2012. Oil on linen. 70 × 60”. Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York.

Fishman: Well, the transitions in the late ’60s and ’70s are much more obvious because I was making radical departures: from making stained grid paintings and, before that, hard edge grid paintings, to taking them all apart. I mean, I literally cut them up and stitched them together. I decided never to paint again, unless it came out of my own experience. Because, I’ve said this many times, being in my woman’s group and examining deeply where everything came from in my work, I realized that I hadn’t had a thought outside of the male tradition of art history and contemporary art history.

Periodically, I’ve gone through this experience, which is to work in a very formal, somewhat geometric framework where there’s a grid that’s there, or stack rectangular images. Then I go from that to the language of the hand, calligraphy and writing. Calligraphy has always been an underlying interest. In the late ’90s, I studied briefly with a Japanese master and I was always interested in and even studied Yiddish, which involved learning to read and write Hebrew letters. So the idea of those marks that were unknown in terms of meaning to me was also true in Eastern calligraphy. My interest lies in Chinese art in general, versus Japanese art. Chinese calligraphy seemed to represent everything to me. Periodically something would happen—it would happen in the drawings more than in the paintings—and all a sudden in the late ’90s, early 2000s, I found myself making calligraphic paintings. There is one in the Tilton show, I forget its name, that was wet into wet with these sort of burnt umber marks that were rather thick. It’s not something I often do. They were almost like birds flying. It had a kind of brushed gray in the back. I had a whole show at Cheim & Read of these very tall paintings that involved a kind of language, a writing language. So I just followed it. After I returned from my first trip to Italy in 1979, I began making marks with my hand that involved the natural curve of the arm and the body; it was the result of having studied the Duccios and the Pieros in Italy. I realized that I had been missing that arm, which I had used as a young student. So to learn how to trust that hand again, that movement of the body, took a while. That was a very liberating thing just in terms of the physicality of it and my allowing it to happen. And I think gradually that language integrated into everything else, until the present moment. In my experience what helps me make decisions has to do with the initial decisions, the size and shape of the canvas. What I am going to work on.

Rail: So the support itself. Or the linen or the canvas or the size and the surface.

Fishman: The support itself. Exactly. It dictates the choice about how I am going to make a mark. I go from the scale of two inches by four inches to 90 by 110.

Rail: Many painters create specific rules for each painting. For instance, they might limit their tools to a specific brush or scraper.

Louise Fishman, “Serenissima,” 2012. Oil on linen. 70 × 88”. Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York.

Fishman: I never do that. I work intuitively. I go over to my painting table and I pick. Sometimes if something is too full of some other paint and I don’t want to stop, I just pick something else, I use a rag or other material. Like in this show, I used wire netting, which was a little hard on my hands because I had to cut it and it had sharp edges. But it’s an impulsive process— I’ll be on the street and just find stuff. I won’t even be sure why it interests me, but I’ll leave it in the studio and sooner or later its either a tool or it gets used in some way in the paintings.

Rail: You thought about the residency in Venice for a long time, and then finally went, and now you have created an extraordinary body of work informed by the experience.

Fishman: It was the most extravagant experience about painting and being alive that I have ever had, in recent memory anyway. Going to Auschwitz was another—it wasn’t exhilarating, but it was intense and had ramifications for years. But this was spectacular. So I thought, how am I ever going to be able to go back and get right to work, because I hadn’t before. It’s always taken me sometimes months before I can get back in. And I walked into my studio and in two seconds I was working. I was working on about three or four paintings and I was getting very upset because there was this odd theatricality about them and there was also, this quality of everything moving up and out, explosively. And I thought, what the fuck is this? I was very critical of it because I tend to be very formal. One day I just happened to look across at this one painting, which is now called “Assunta” and I thought, what is this? Next to it there was a postcard of Titian’s “Assumption.” And I looked and I thought, for Christ’s sake, its all about Venice, it’s all about this drama in these paintings. And it’s about the sky. So it all came to me and it was a tremendous relief.

Rail: The paintings made you uncomfortable because they were so different from your previous work?

Fishman: They did. I felt like I was losing it. I’ve never had anything that just sort of did that. I mean, they’ve gone all over the place but they usually somehow evolve with something that ties them to the ground. Standing on the floor and having the weight and movement of your body dictate what happens, it can go all over the place, but it stays within the confines, not necessarily of the rectangle but of a certain distance outside of the rectangle. And this was way off, it was going off into the skies. And I was in a very exuberant place. Ingrid was now in my life in New York. I never thought I would meet anybody at my age. I have a Buddhist practice and I try to be compassionate in the world, so suddenly to have things come to me was not easy. I mean, I used to get migraine headaches if something happened that was good. Because, you know, God was going to strike me dead. That was in my family, my mother was very superstitious, if you sing before breakfast, you’re going to cry before dinner. And watch out because they’re going to come and get you. I mean it is something that as a Jew, coming from a European tradition, was endemic. I assume any outsider might experience similar feelings. So, this was a very big change.

Louise Fishman, “Crossing the Rubicon,” 2012. Oil on linen. 66 × 57”. Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York.

Rail: So you questioned the paintings, because everything else was going so well, the paintings were confusing and unexpected.

Fishman: Now I look at the paintings in the installation and I see the terrific exuberance in them. They have everything of me in them, and they are about this very moment.

Rail: You are from a family of artists. You have an upcoming show in Philadelphia that includes paintings by your mother and your aunt Razel Kapustin, who was a prominent Philadelphia artist.

Fishman: I don’t think I’ve really paid attention to the connections with my mother and aunt. I’ve always said, “Oh yeah, they were painters but I wasn’t interested in what they were doing.”

Rail: So many of our influences are so unknown to us. Anyone looking from the outside might see them immediately, and yet, we seem to know so little about ourselves.

Louise Fishman, “Lolland,” 2011. Oil on linen. 32 × 24”. Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York.

Fishman: That is so striking to me now; during the last few months as William Valerio, the director of the Woodmere Art Museum, began putting the works together by the three of us, my mother, my aunt, and myself, I was stunned by the connections he was able to make. He has worked hard to restore Razel’s reputation. She was a major artist in Philadelphia and he’s told me things that even I never knew about her. He has pointed out things visually that I had never seen. And so here it is, and I’m reviving the careers of both Razel Kapustin and Gertrude Fisher-Fishman, which is a major achievement.

Because of the intimate nature of the exhibit at the Woodmere, I selected work of mine that has never been seen by the public, for example, a drawing I made when I was 5 or 6 called “Food Coupons for Imaginary Brothers and Sisters,” which could be considered my first grid. These paintings that I have kept for myself that I assumed no one would be interested in. They are like family photos, that’s how personal they are. But they’re really interesting as art. In a way, it feels like they’ve been stolen from me. Its like, “What happened? The family jewels disappeared [laughs.]” or something, and they’re there and how does that influence re-entering my studio at this moment?

Rail: Once other people see those paintings, you may see them in a different way that’s colored by people’s response to them. How the paintings are received might affect the way you move forward.

Fishman: Well, just seeing my own paintings at Tilton, in a different environment—with air and light and ivy on the walls outside and something about the plaster walls and it being a living space—has changed my whole sense of those paintings. I think that’s sort of the primary thing. Rather than how other people look at them.

Rail: I recently read an interview in which you said at the end, “I want to make the best paintings I can.” I wondered what that might mean for someone who has been painting for more than 50 years.

Louise Fishman, “Longhand,” 2007. Oil on linen. 66 × 39”. Courtesy of the artist, Tilton Gallery, New York and Cheim & Read, New York.

Fishman: Contrary to what a lot of people think, being a painter, making paintings, continues to evolve. I really believe that, or I wouldn’t be doing it. And so for me, I’ve made, I don’t know, probably thousands of paintings and I have thousands and thousands of drawings that no one has ever seen. I’ve been doing this and I know that even though I used the same, some of the same tools, visual tools, as well as physical tools, that there will always be discovery. Every time I go somewhere, I notice something visual, and it ends up ultimately in the work. Esther Newton, a former lover of mine, and an esteemed cultural anthropologist, wrote a paper on consciousness-raising in which she compared it to religious conversion theory. My experience in Venice and the work that followed could be considered comparable to religious conversion, although it has nothing to do with religion. If I couldn’t introduce new experiences, materials, ideas into my work, I would be bored and there would be no reason for me to continue. One thing I will not do is make paintings that don’t teach me something. I often destroy something—not destroy it and throw it away, but scrape it down or repaint it or something, unless it really does something that’s like, “Oh!” and teaches me something. So when I say “I want to make the best paintings I can,” I mean I provide myself with the freedom, the time, the resources in terms of what I’m looking at, enough money to continue this process—which at times has not been there, and will probably continue to go up and down and up and down. So, given that things are relatively in place, that’s what’s important now. The painting, and my experience in the studio— and I think most painters would say this— is really all there is. The rest of it is fluff. One has to be careful not to get seduced by success, which is really difficult and, particularly for young people, but even at my age, it’s very seductive. Things that happen around one’s work, when there is a positive response out there, can turn in a second. The audience for art is very fickle. I just want to be able to be in that studio, listen to music that I love, and continue to change, so that there’s a flow somehow to the work. I want to be alive, to have a really alive experience of working.