December 2, 2020

Download as PDF

View on The Brooklyn Rail

Louise Fishman, AYZN, 2020, oil on linen, 36 × 24 inches; 91.44 × 60.96 cm

What a brilliant cacophony of abstract gesture, I think to myself while taking in Ballin’ the Jack, Louise Fishman’s first solo exhibition at Karma Gallery in the East Village. The oil paintings on view in the main gallery revel in their messiness: thick strokes of paint crash into each other, clashing colors fighting for dominance, while the white gesso underneath reveals itself as a seductive promise of transcendence. In Karma’s smaller space, by contrast, Fishman’s watercolors on paper wait quietly. While undeniably in dialogue with the oil paintings, these soft, almost translucent compositions seem as if they were made in a different state of mind entirely. Hovering on the walls like tantric mantras, their small size invites closer inspection and therefore a more intimate encounter.

Would I like these paintings if they hadn’t been made by Louise Fishman? This is an interesting question. I’m as far from a formalist as Clement Greenberg was ever a feminist: it’s social art history that interests me. And the truth is, I have long held Fishman in the highest regard, with an intergenerational kinship so strong that when I finally met her on this exhibition’s opening day, I felt like I already knew her. Queer queen of abstract painting on par with Agnes Martin, Fishman—unlike her predecessor—has been an openly out lesbian since the 1970s, a time when being queer was guaranteed to have serious professional consequences. I cannot separate the courage of this personal gesture from the boldness of Fishman’s artistic gestures. To me, they are the same. Fishman and her paintings are inextricable—they feed off of each other.

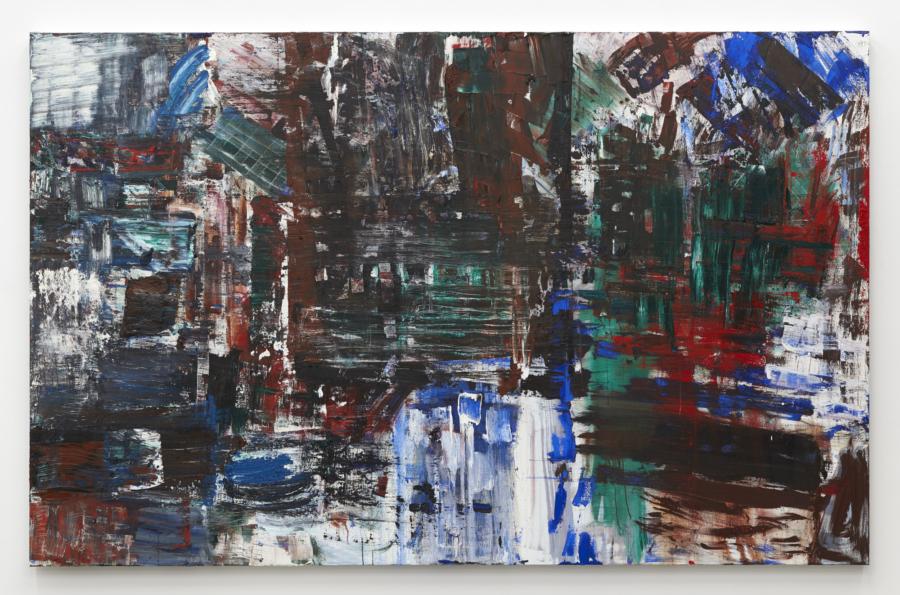

Louise Fishman, Dugout, 2020, oil on linen, 70 × 110 inches; 177.8 × 279.4 cm

In 1977, Fishman co-edited the legendary “Lesbian Art and Artists” issue of the feminist magazine Heresies, and contributed a piece of writing on her painting process.1 In here, Fishman cautions against the forced use of lesbian imagery, urging lesbian artists not to limit themselves in their sources of inspiration. “By all means look at Agnes Martin, and Georgia O’Keeffe and Eva Hesse,” Fishman writes, “but don’t forget Cezanne, Manet, and Giotto.” This statement speaks to the confidence that is so palpable throughout Fishman’s oeuvre. She is not shy to take what she needs from artists who likely would not have acknowledged her during their lifetime. She is not afraid that her work will mistakenly be read as blindly following what the AbEx boys did. It has been her lifelong commitment to reclaim a traditionally gendered painting style for all the dykes out there, and for this she is to be greatly admired.

Louise Fishman, Mondrian’s Grave, 2018, oil on linen, 110 × 70 inches; 279.4 × 177.8 cm

No review of Fishman would be complete without mentioning her “Angry Paintings” from 1973, beautifully described by art historian Catherine Lord as a “calligraphy of rage.”2 Executed in acrylic, charcoal, and pencil on paper, each of these gestural abstractions had the word “angry” followed by a female name inscribed into its surface. An ode to women of importance in Fishman’s life, whether practically or spiritually, contemporary or ancestral, the names included Harmony (Hammond), Jill (Johnston), and Gertrude (Stein), to name a few. These paintings arose from Fishman’s rage at heteronormative and patriarchal structures that dominated the art world, marginalizing her and her queer women peers. It was in this series that Fishman’s signature messy application of paint came to its full fruition, and it has not left her practice since. In Dugout (2020), one of the most powerful pieces in the show at Karma, sturdy strokes in a palette of blues, browns, greens, and reds move both horizontally and vertically with a bellicose sensibility. The painting appears almost geological, like saturated wet soil after a flood, or the smoldering aftermath of a volcanic eruption. In another highlight, A La Recherche (2018), whose title refers to Marcel Proust’s famous novel, the mood is more serene. The primed canvas proudly holds its own, with only a few painterly gestures in blue and red applied so thin that they look like bruises—a bruised body after a night of passion, perhaps, to suggest an image of which Proust himself would likely approve.

Then, of course, there is Ballin’ the Jack (2019), the painting that lends the show its title. Here, elaborate gestural movements in dark brown with hints of turquoise and pink bear comparison to Franz Kline, who Fishman sometimes identifies, along with Joan Mitchell, as an important influence. A phrase unknown to this Russian Tatar writer, “ballin’ the jack” apparently means “going at full speed.” And what better way to describe Fishman’s practice than with such a rush and energy, all rooted in queer rage? In a piece that Fishman edited for that same 1977 issue of Heresies, documenting a conversation between 10 lesbian visual artists (including herself), one of the artists notes: “We each carry around enormous rage. I think that the threat in my life has been that my rage would destroy me, and until very recently, that has been a real possibility. We need to focus our rage so that it becomes usable energy.”3 This quote holds true for Fishman’s practice. While there is no text in the new pieces on view, I feel that angry Louise is still there, lurking underneath the surface. Watch out, boys: Louise Fishman, going full speed ahead.

- Louise Fishman, “How I do it: Cautionary Advice from a Lesbian Painter” in: Heresies 3: Lesbian Art and Artists (Fall 1977): 74-75.

- Catherine Lord, “Their Memory is Playing Tricks on Her: Notes Toward a Calligraphy of Rage,” in WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution, 440-457.

- Louise Fishman, ed., “The Tapes” in: Heresies 3: Lesbian Art and Artists (Fall 1977): 20.