December 14, 2018

Download as PDF

View on Juxtapoz

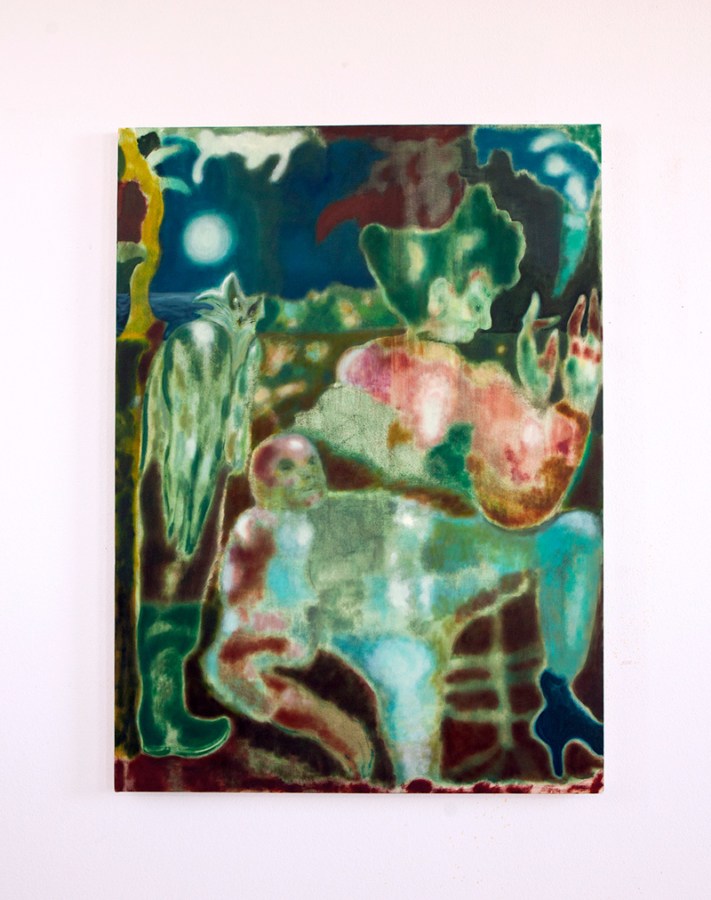

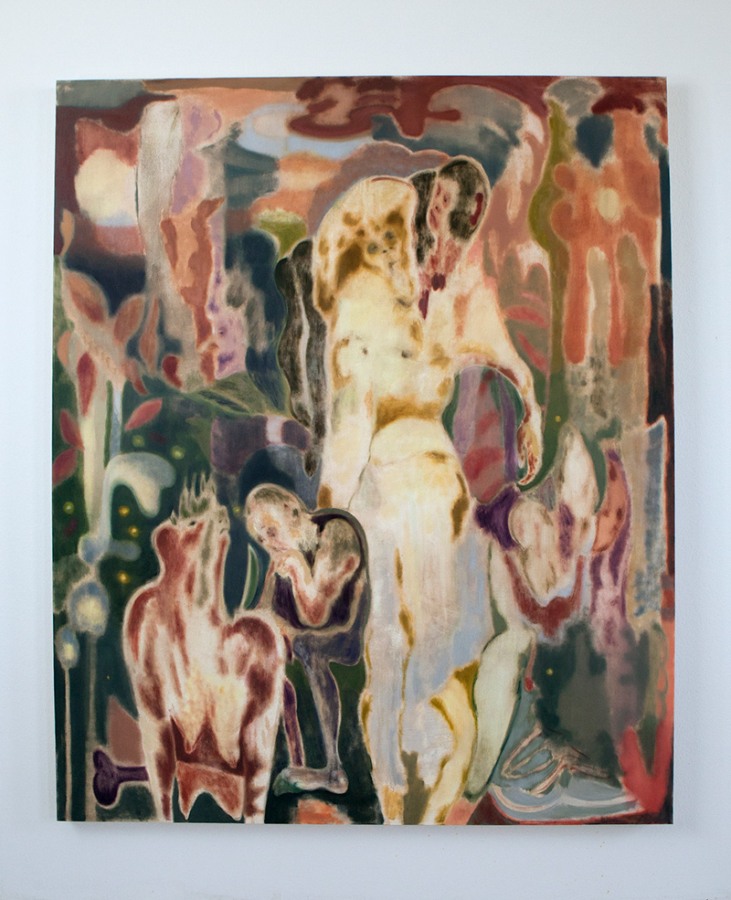

Our friend and filmmaker Theo Schear went down to Roswell, NM a few months back to explore the world of Maja Ruznic and Joshua Hagler, two contemporary artists who have immersed themselves in an unlikely place to dig deeper into the fabric of their experiences and their history.

Around that same time, we talked with Ruznic about the weaving myths of her practice and how someone so direct and spiritual gets by in 2018.

Juxtapoz: In a recent interview, you mentioned how your interest in myth and trauma are deeply connected to each other. Could you explain in what ways? How does this relate to your work for you and for your audience?

Maja Ruznic: My interest in trauma stems from my childhood experience of being a refugee. However, this traumatic event—the war in former Yugoslavia– was only the beginning of a cascade of adverse experiences that later affected me—living in poverty, not knowing my biological father, not speaking the languages of the countries where we lived (Austria and the US) to name a few. In other words, while most kids were learning to read and write, I was watching my mother wash food scraps that were donated to the refugee camp by the local hospital, and then frying them to ‘kill the germs’. The need to survive was forcefully present everywhere I looked. Suffering is something I felt very acutely as a kid, and now as an adult, I try to make work that hopefully evokes empathy in the viewer. Empathy is something that is not present during conflict, so I try to insert it into the world through my art because I feel a shortage of it today.

Having fled from a politically divided place and now living in one, I feel the need to speak in a way that is not direct, but rather, reaches people below the surface and touches a place in them that is nonverbal and pre-judgmental. I’m trying to communicate something that is not within the good-bad binary because I know that the only response one can achieve then, is reactive. So naturally, mythology serves as the perfect platform to address conflict, trauma, pain, and love in a way that seems eternal—mythology as a vehicle to connect us to times before and times to come.

I think of mythology as a kind of slow food, and methods that are more didactic, as fast food. There is art that in an instant can tell you what to think—like that rush you get from having a bite of a burger for example. Because the times that we’re living in are so inflamed, people are more reactive. So, I don’t feel that I need to make art that evokes quick reactions—there is plenty of that everywhere. Instead, I feel a deep calling to make work that seeps into people’s bodies and evokes feelings that are hard to name. I’m interested in a slower processing of information, so my work, which weaves mythology with today’s conflicts, is the way in which I contribute to what I call the ‘slow-art movement’. What’s powerful about myth is that the events and conflicts within them are forever relevant and mirror back to us, the full spectrum of human behavior that has always existed.

Lastly, painting for me is about hope. The sensual and physical quality of applying paint to the surface connects me to the earliest humans—the pleasure of the process, affirming that I’m still here—that we’re still here.

In what ways would you describe your work as sincere? How has this changed throughout your time painting?

Perhaps the way in which my paintings are most sincere is in their directness. I don’t do any preliminary sketches or use references, so everything happens at once—thinking, erasing, re-stating, etc. I want the playfulness of intuition to be in the painting, so I don’t separate thinking-through and creating. The union of thought and mark making is in fact how the whole thing works. So my paintings are about meaning rising out of the process—the image and story come to form at the same time, continuously informing each other.

Secondly, the figures in my work come, as they are—amorphous, tired or fresh, they show up to the party without checking themselves out in the mirror. Immune from the impulse to deceive through conventional beauty standards, they are the first to celebrate their own imperfections and shortcomings. One leg or two, they share with other each other if one has too many limbs and dance despite the fact that everything around them seems to have fallen apart. It is their laughter, with which the world is rebuilt.

What brought you to New Mexico? How long are you there for and how has it affected your work?

Josh, my fiancé and I moved to Roswell about a year ago. He received the Roswell Artist in Residence Grant, which provided both of us with free housing and studios for an entire year! This time has been transformational. Growing up in San Francisco and living in Los Angeles prior to moving here, I was hesitant about the thought of living in a rural place. To my surprise, I fell in love with the landscape immediately. Having all the time in the world to paint, write and engage with my work has been something I never had the privilege to do before moving here. In California, I always had multiple part-time jobs, which really chopped up my studio time into tiny fragments. Having a large studio and unencumbered time to think and make has allowed me to go deeper into the work and raise the bar for what I expect from myself in the next few years.

Where do you see yourself in the larger tradition of art and where do you see yourself in the tradition of makers in your family?

If I’m lucky, my work will get grouped with Edvard Vuillard, Helen Frankenthaler, Marlene Dumas, and Mark Rothko, to name a few of the greats. For me what all of them have in common is a deep love for paint and a commitment to big human questions and emotions. There is romanticism in how they create which is inspiring to me—a kind of a love affair with paint. This sensuality and tenderness is important to me as I feel that it touches upon the complexity and rawness of being alive. Their work does not tell me how to think, what political side I should be on and most importantly, their work does not try to teach me anything. If my work achieved even a fraction of this, I could die happy.

My mother and sister are both artists. My mother refurbishes vintage clothing for a living. She has a special eye for textiles, color, and composition. My sister, Alma (Alma Rosae) is a singer and rapper. From the time that she was five years old, she was singing and winning various talent competitions. I think all three of us are bursting with emotion and the need to connect with others through our art. Even as an immigrant and refugee, my mother always pushed us towards art, literature, and music. Somehow, she always knew that this is where Beauty lies and that without it, a soul dies.

Throughout your everyday life, where do you feel like you stumble upon things that inspire you most often? Is it a place or a more general situation?

My cat, Judith inspires me. Really—it’s the intensity of love I have for her that moves this emotional engine inside of me. She is a little feral creature we adopted about 6 months ago. She is wild and full of wisdom; so naturally, we named her after one of the “Where the Wild Things Are” characters. Another badass that shares her name is Judith Butler. Another thing that inspires me is the tenderness I can experience with strangers with simple gestures—like a smile in the grocery store. My partner, Josh Hagler inspires me–his commitment to asking the difficult questions and unapologetically making epic, beautiful paintings. The sky before a thunderstorm, the smell of soil when wet. The Roadrunners all over our neighborhood, the Jackrabbits, the deer. My mother. My sister. All survivors. All things and people that keep moving despite pain and suffering. The sunflowers. The other stray cat that we feed in the morning—her big green eyes and her tiny body. I also find inspiration in the books I read. I’m currently reading David Wojnarowicz’s “Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration” which is brutal and important. What I read is hardly ever directly connected to my painting practice but certain words or phrases ruminate in my brain while I work and I can only imagine that something about it gets through in the painting.

Name some areas of your work that criticism that has helped, and name some positive areas that you felt held back from because of criticism.

Being in a relationship with Josh, another artist, and a painter means that we’re looking at each other’s work ALL the time! I feel lucky in that way—getting mini-crits throughout the day. He is also my number one fan, who believes in me even in times when I don’t—this gift is priceless.

A criticism that didn’t help happened in grad school from a teacher. I was making a series of portraits of my family members in Bosnia and he said, “Bosnia isn’t relevant right now. It’s Iraq.” This was back in 2007-8. I remember thinking about the word ‘relevance’ and how it can be a tool of power in the art world. Relevant to what? To who? Can wars be trendy like fashion? Is the art world just another trend-obsessed market? Although brutal, my teacher’s proclamation that my family portraits are irrelevant equipped me for what was to come and helped me shed the first layers of naiveté.

This last one is not so much about criticism but about a realization. I was at a meeting with a curator, a friend, and another artist a few years ago and felt completely ignored by this curator—until my friend dropped the “Maja was a refugee as a kid” line. Immediately, this curator shifted her dress, turned her chair to face me and passionately inquired about my past—like a vampire sucking blood. All of a sudden, I felt seen by her for the first time. As if I, the body, the person, the artist did not exist without the I-the story. I realized that it wasn’t the art that ultimately got her interested but the stories about my life that she could write about. I vomited after this meeting. Too much truth to swallow at once.

What’s something you constantly have to remind yourself to stop from spiraling?

Josh always says: “The work itself has to be the greatest reward!” I try to remember that when I feel like I’m not being part of the larger conversation happening in the art world. Sadly, one can feel seen or heard only when the ‘gatekeepers’ have invited you to the ‘big dance’. Keeping one’s eyes on that can make a person go crazy. So, Josh’s little phrase keeps me centered. It reminds me why I do this thing in the first place.