March 12, 2020

Download as PDF

View on Brooklyn Rail

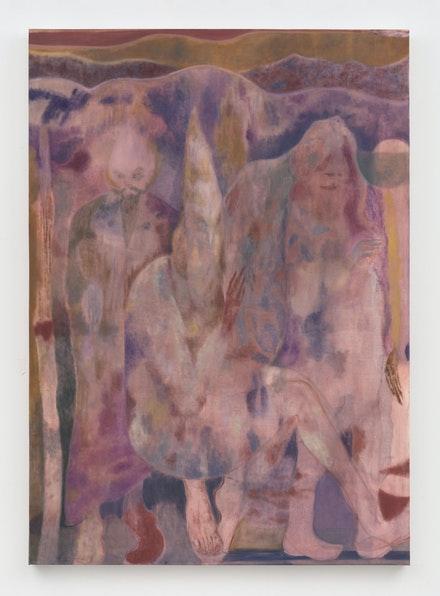

Maja Ruznic, Ukazanje, 2019. Oil on canvas, 80 × 57 inches. Courtesy Hales Gallery, London and New York. Photo: Stan Narten.

When the term magic realism first appeared in art history, it was most often used to describe the work of artists like René Magritte and Giorgio de Chirico, whose strange tableaus challenge the viewer’s perception of reality. Many years have passed, and magic realism is not now a term widely used in reference to contemporary art. The current group exhibition at Hales Gallery in New York, however, brings together seven contemporary artists in an effort to highlight the fact that many still turn to magic realist strategies and imagery in their practice.

The exhibition title, The Moon Seemed Lost, refers to Italo Calvino’s short story Daughters of the Moon (1968), a magic realist narrative in which the moon no longer functions and therefore has to be removed. The precariousness of the moon in Calvino’s story functions as an apt metaphor for adversity and personal trauma, experiences that many of the artists included here are processing through their work. This is what most powerfully distinguishes their work from the magic realism of a century ago: unlike the artists of the early 1910s, who focused on illusionistically rendered—if enigmatic—motifs drawn from the outside world, the artists in The Moon Seemed Lost instead turn inward to themselves, their loved ones, their histories, and their origins.

Making up more than half of the exhibition, it is undeniably the medium of painting that is highlighted here. Drawing from queer archives and family albums, for example, Anthony Cudahy creates highly painterly compositions that build on the art historical legacy of academic painters such as Alexandre Cabanel and Albert Joseph Moore. At the same time, they share the sketch-like quality of contemporaries such as Salman Toor and Peter Doig. One of the three works included is a tender portrait of Cudahy’s husband, titled Ian (with Friedrich’s rainbow) (2020). Cudahy cites Caspar David Friedrich as a primary source of inspiration, and here he invokes Romanticism’s introspective emotional world by depicting his lover with knees curled up and eyes cast down.

Two paintings by Maja Ruznic are executed in muted hues of green and pink, not unlike those employed in Cudahy’s work, thus creating a palpable visual dialogue across the gallery walls. A refugee from Bosnia, Ruznic’s work taps into her personal memory of migration. Rendered in thin, almost translucent layers of oil paint, the artist’s figures appear ghostly and dissolve into their surroundings. Stylistically, this device recalls the depiction of movement in El Greco’s later works, but thematically it invites contemplation of the ways we are undone by histories of trauma.

TM Davy is known to honor queer relationships, and the two paintings included in this show do not disappoint in this regard. One pictures the artist himself with the sun, while the other is a portrait of his husband, Liam, with the moon. Both works depict the figures cloaked and floating above the clouds, radiating a kind of spirituality that is common in Davy’s painting. Of the artists included here, it is perhaps his work that shares the most with the “original” magic realists. However, Davy’s meticulously illusionistic rendering of three-dimensional space and the effects of light are less about defining form and matter, and instead serve his interest in transcendental and interior states of being.

Complementing these paintings are works that employ various other media. Omar Ba, for example, employs gouache, acrylic, and ink to create a politically charged but ultimately celebratory depiction of his home country, Senegal. A repeated pattern shows figures integrating with surrounding fauna, suggesting a capacity for human transcendence through nature. A photograph by Rotimi Fani-Kayode depicts a mysterious figure, face covered by dreadlocks, holding up a branch of grapes in a ritualistic gesture that is both spiritual and sensual. The Nigerian artist ruby onyinyechi amanze takes inspiration from the work of choreographer Pina Bausch, and considers dance alongside geography in a hyperrealist paper rendition of two figures with leopard heads performing a duet. Finally, a sculpture by Sarah Peters placed on a pedestal in the center of the gallery, balances Greco-Roman and science-fiction aesthetics in the form of a floating head with hollow eyes.

While the show would’ve perhaps been more cohesive if it had stuck solely with painting, the artists’ common interest in magic realism is nonetheless discernable across all the media included. The dysfunctional moon described by Calvino’s story and the exhibition title could not appear more timely than today, as we face the instability of our own planet and society, our movement is drastically restricted, and we are forced to turn inward. Similarly, the exploration of magic realism in the work of the artists featured by Hales Gallery is inherently personal, turning inward to contemplate where one comes from and imagine alternative futures that are, first and foremost, rooted in the self. As Proust once wrote: “The real voyage of discovery consists, not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.”