June 14, 2018

Download as PDF

View on Art Maze Magazine

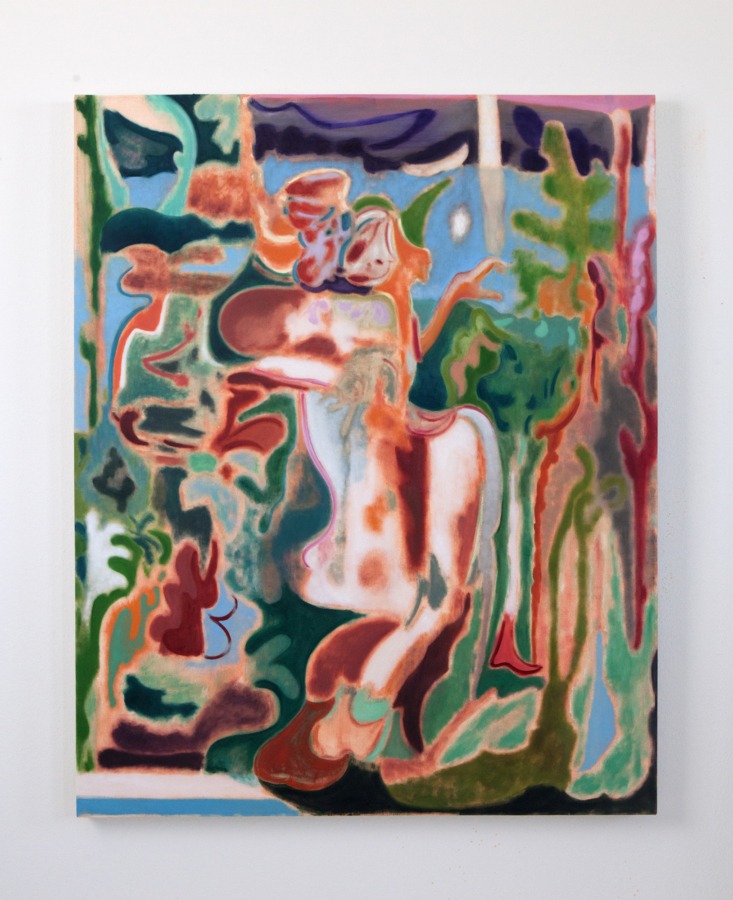

San Francisco-based artist Maja Ruznic’s paintings allow ethereal entities to emerge from the surface and move across the composition, blending into one another. Using washes of vibrant oils like watercolor, figure and background begin to merge, making the subjects appear ghost-like, airy and beautiful. The compositions of her paintings are often filled from edge to edge with layers of abstracted form spread throughout. These works radiate with electricity, as if they contain their own pulse, not just within the figures that appear within each piece, but also within the entirety of the work itself. This rhythm becomes almost spiritual, creating a connecting between her work and the viewer.

Ruznic’s lifelong fascination with mythology and the human psyche has continuously inspired her subjects not just within her paintings, but also in her soft, sculptural “Phantoms” as well. Join us as Ruznic discusses the influence three strong women in her family has had on her work as well as the relevancy of trauma and healing to her practice.

AMM: Let’s talk about your artistic background. Did you always consider yourself an artist? Was your creativity encouraged growing up?

MR: I didn’t have that same certainty or calling, like many of my friends who always knew that they’d be artists. However, looking back at my childhood, I can see that my mother and grandmother instilled a certain way of looking at the world that I feel is connected to being a creative individual. Before the war in Bosnia, my mother often travelled to Greece and brought me back books about mythology populated with amorphous creatures. I found them fascinating. Unlike typical children’s toys, I found the mythological creatures more interesting. They were mysterious, scary as well as powerful. I also remember watching David Lynch films with my mom when I was seven. I don’t think most parents would allow their children to watch Twin Peaks, but my mom and I craved a good psychological thriller. In that sense, I think my mom was my first art teacher. At an early age, she opened the door for me to the more complex elements of the psyche, and I became intrigued with the fragility as well as the resilience of the human body.

My nana was a devout Muslim and I remember being fascinated by her commitment to her religion. Her daily washing of feet, hands, and arms up to her elbows, followed by prayer, was a deeply comforting and mysterious ritual to witness. It was her time to herself and I could feel that it was sacred. So, Nana was my second art teacher. She helped me see that being connected to something greater than oneself is to be connected to the Eternal.

AMM: The figures in your paintings appear like ghosts among backgrounds that they blend into. How do you create this unique, otherworldly effect?

MR: Prior to working with oils, I spent six years working with ink and watercolor. It was primarily a financial decision after graduate school because I could not afford a studio. To ensure that I wasn’t killing my lungs in my small bedroom in San Francisco, I started painting with water-based media and quickly fell in love with the medium. When I returned to oil, I wanted to keep that ethereal quality and experimented a lot! I learned that thinning out my paint would give me that stain-like quality. It was cheap and effective! I learned to approach oil painting the same way I used watercolors — starting with the lightest colors and slowly building towards the darkest, so that at the end, all the light is coming from the first layers. This is important for my work because I try not to paint the light but instead, leave the light from the early stages and allow it to emanate from beneath.

In addition to painting really thin, I flip the canvas around as I paint, finally settling on an orientation after a couple of sessions. This allows for strange shapes and compositions to emerge without having to commit to anything too soon.

Lastly, I never approach a painting with an idea. I’m actually quite sceptical of the Western way of thinking about intelligence — as the brain being the CEO. So, I check in with my gut, feet, thumbs, throat, which allows for shapes and colors to emerge in my mind’s eye. It’s like activating pressure points in my body, which in turn gives me imagery that appears abstract at first and through the process of painting, becomes more recognizable.

AMM: Can you talk a bit about the narratives and mythologies present within your work?

MR: I’ve been thinking a lot about Mokosh. She is a Slavic Pagan Deity and protector of women’s destiny: spinning the thread of creation, giving life and cutting the thread. She is associated with fertility and healing and has a special connection to sheep, wool and textiles. She has two children, Jarilo and Morana who I have also painted. I grew up without a father so my life has been full of women. My mother, nana and aunt raised me. One could say, they were my Three Fates and all three have a special connection to textiles. My mother and aunt refurbish vintage clothing for a living and my nana often travelled to Italy to purchase the latest trends. I try to make my paintings look like they are tapestries or as if they’re painted silk. Recently, I realized that perhaps, my practice is my continuous love letter to the three of them.

The figures in my work often look like they are engaged in some sort of ritual or are on a journey. I’m reading a lot about Shamanism and religiosity at the moment as well as more practical books about the effects of childhood adversity and trauma. Mythology allows me to speak about human suffering in a softer way than if the work was more literal. Surviving a war has taught me that sharpness, emotional as well as physical, creates division and perpetuates violence. So I take this idea of softness and apply it to the actual process of painting — scumbling, blurring and allowing shapes to bleed into one another. Symbolically, I’m trying to destabilize borders. I see myths and stories as having more welcoming shapes — soft and round like stuffed animals. I feel called to communicate not to the brains of people but to their bones and hearts. I hope my work activates something nostalgic, familiar and even sad. Myths are full of darkness and suffering but beauty in how they’re told.

AMM: Tell us about your sculptural, figurative work such as “Lady’s Man” and “Blue Eyes” that were in your most recent solo show Avet at Conduit Gallery in Dallas. When did you start creating these figures? How do they relate to the subjects of your paintings?

MR: I started making the Phantoms in the summer of 2017. I wanted my paintings to breathe more and the only way to actually do that was to literally let the canvas rest between sessions. Up to this point, I found my paintings cluttered, clogged and heavy. Around this time, I visited the MOCA in LA and was floored by the Rothko paintings in their Rothko room. I’d seen Rothko’s work before — many times, but never felt like they put me in a trance like the ones that day in LA. There was something special about these particular Rothko paintings — they were devastatingly sad. The palette was dark and moody. I cried in front of art for the first time. Walking away from the museum that day, I kept thinking “breath”!

When I returned to the studio the following day, I started arranging scraps from old clothing and stitching them together. I had no goal in mind, except that I needed my hands to stay busy and the paintings to be left alone for a while. I’d stitch for a few minutes, then look up at the painting and make mental strokes and erase them. Then back to stitching. Before I knew it, the first phantom was born and the first painting was made that I actually felt had the sense of breath I was trying to capture. That painting is “The Poet, the Mother and the Search”.

AMM: Your figures made of fabric have an imperfect aesthetic that allows the viewer to see elements of the process such as the stitching. Does this artistic choice reference voodoo dolls or perhaps handmade dolls in general?

MR: I don’t think about voodoo dolls even though I am aware that my phantoms evoke that comparison. I do, however, think about what Mircea Eliade calls ‘hierophany’—which is the idea that the sacred can be manifested in objects or places. He says “Every sacred place implies a hierophany, an irruption of the sacred that results in detaching a territory from the surrounding cosmic milieu and making it qualitatively different.” I am not intentionally imbuing the sculptures with any form of magic but my movements and stitches are recorded in the form. My gestures are loose and quick and I think people tend to associate that with the dark and voodoo. The Phantoms end up looking a bit pathetic and sad and I hope that this evokes more empathy in the viewer and less fear.

From the time that I was a kid, I collected what I called “sacred” objects — rocks I found on my runs that seemed to radiate something different than the other rocks, buttons from favorite shirts, feathers, etc. Phantoms for me are a way of manifesting the sacred through a kind of anxious energy. I think different people as well as animals and plants run on different frequencies — some slower, others faster. I think of myself as a very high frequency person with a ton of nervous energy, which I also see as surplus energy. Phantoms become a way to channel that mania. I think that’s also why they look so rough — while making them, I try to leave all the traces visible, and allow the viewer to witness how limbs are connected to each other.

AMM: Where did you study art? How did this experience influence your body of work?

MR: I did my undergrad at UC Berkeley, where I studied Psychology and Art and received my MFA from California College of Arts in San Francisco. I only realized that I wanted to study art mid way through college. I took art classes for fun and wasn’t the best student in class. I don’t think any of my teachers would say that I had a special talent for drawing or painting. I remember getting B’s and C’s on my projects even though I worked really hard. There was nothing really special about my early days as an art student except that there was one older student who intrigued me. Sadly, I don’t remember her name but she was the person who made me curious about developing my own painterly language. She’d come to life drawing class and while we all tried painstakingly to render the human body, she’d come up with drawings that looked like something de Kooning would make. She made me go “AHHHHH!” She was fearless, unique—a total badass. I wanted to be like her! During my senior year, I was nominated to be in the honor studio, which was a surprise to me. At CCA, I only had a couple of teachers who made me feel good about my work. To be totally honest, it was a brutal experience. I remember one teacher telling me “Bosnia ain’t hot right now, it’s all about Iraq!” in response to a series of portraits I made about my family in Bosnia. I felt so small and cried after the critique. Luckily, there were a couple of teachers who didn’t seem as ‘trendy’ and had a depth that I found very comforting.

In retrospect, I’m glad I got the support as well as the criticism, as both prepared me for what would come after school. I realized quickly that the art world, much like the fashion world, is one big Trend Conveyor Belt. At the time I graduated (2009) sincerity was not in. Luckily, I also realized that I don’t need to be cool, and that poets and deep thinkers ALSO exist in the art world. It’s one big, complex community!

AMM: Originally from Bosnia and Hercegovina, when did you make the move to the US? Does your heritage influence any aspects of your work?

MR: The war in Bosnia started in 1992 and my mom and I fled right away. We lived in refugee camps in Austria between 1992-1995, and arrived to San Francisco, CA in 1995. I think my interest in trans-generational trauma has everything to do with my childhood experience of being a refugee. The sense of being adrift, not speaking the language, being poor and living on food stamps — all contribute to my interest in psychology, trauma and healing. My phantoms are manifestations of the abject that I hope evoke empathy. I listen to Bosnian music a lot when I paint. I feel that it activates a different part of my brain and puts me in touch with my ancestors. I can’t prove this in any way, other than that it feels different to paint while listening to music in English, which makes me feel more psychologically sober. Sevdah, Bosnian folk music, for example, makes me feel like I’m floating through fog and layers of time, where people cry and waltz together in order to remember their dead relatives.

AMM: You work with materials such as oil, acrylic, fabric, and buttons. What other materials have you experimented with? Have you ever experimented with a material that did not go well?

MR: I recently took a ceramics class and must say that I have a new respect for the medium. Especially throwing — I find it super hard! I’ve made a few clay phantoms but don’t like how they turned out. I realized that glazes are key and I haven’t found one that I love.

AMM: If you are ever in need of a break from working on your art, what do you do to recharge and get inspired?

MR: From years of running in high school and college, I’d say that being athletic is my other passion. I love yoga, hiking and running. Health is important to me and I enjoy taking good care of my body. When I’m really stuck with a piece, I like to go to the local bookstore and find a good book. Reading is a guaranteed way to re-invigorate my practice. I recently finished the Matrixial Borderspace by Bracha. L Ettinger, which I found mind blowing. In this book, she intertwines philosophy, art and psychoanalytic theory and critiques the phallocentricism of Lacanian theory and offers something beyond the masculine-feminine opposition. She is such an important voice, especially today! I find her way of speaking about trauma very relevant to my practice.

AMM: Where do you see your work going next? Do you have any plans for your art currently in the works?

MR: I’m working on a project with the Center for Youth Wellness (CYW) in San Francisco, CA, which we’re hoping, will come to fruition in the fall. I heard Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, the founder of CYW, give a TED talk on childhood adversity a couple of years ago and it left me feeling both hopeful that someone like her is doing important work to address the effects of childhood trauma, but also devastated, realizing how many people are affected. I just finished her book, “The Deepest Well”, in which she addresses the causes of childhood toxic stress and offers ways to heal. Our project will be an art show-fundraiser where 60% of the art sales will go directly to benefit CYW.