July/August 2020

Download as PDF

View on Artforum

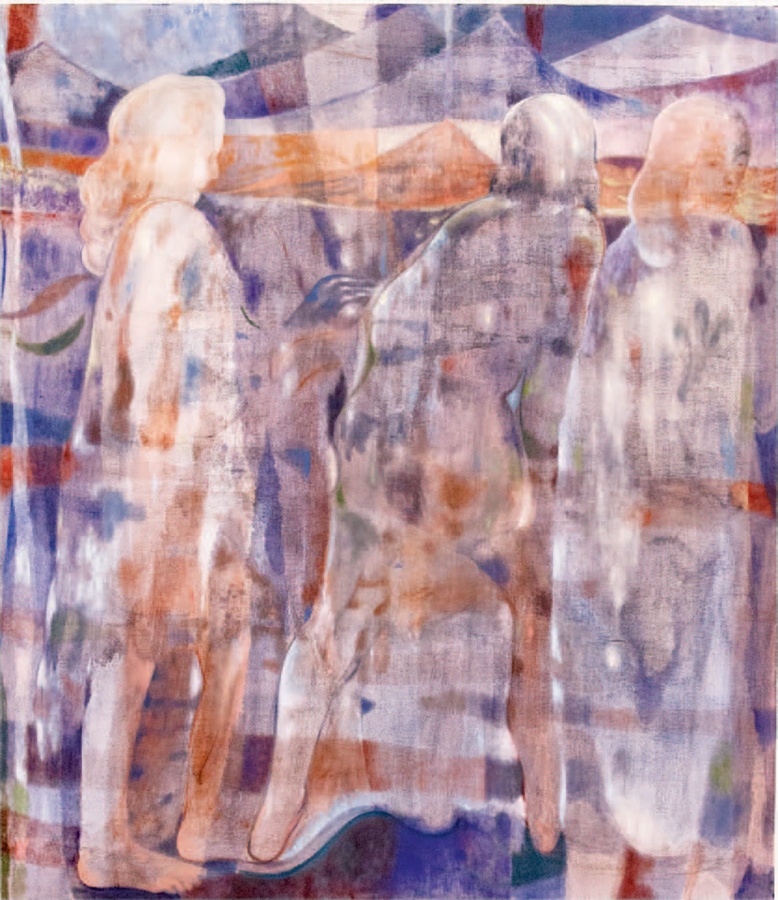

Maja Ruznic, Truth Seekers, 2019, oil on canvas, 70 × 60 inches

Everything appears to be in a state of constant and inevitable change in the exquisite paintings of Maja Ruznic. A range of mark-making methodologies leaves the images wraithlike, insinuating echoes of ideas. Ruznic stains her works with Gamsol-saturated pigment such that nebulous pools of paint fade in and out, sometimes disappearing into the weave of the canvas. The look is reminiscent of a watercolor bloom. The artist does not, however, rely on this procedure; it is only a beginning. She then examines the results of her incidental color placements and nimbly pulls forms from the foggy washes. The paintings come alive with the assuredness of her hand drawing figures out of the canvas, outlining a foot or a rudimentary face.

In loose, dreamy groupings, Ruznic’s aqueous humans overlap, sit side by side, or diaphanously mesh into singular beings. Most appear to be women. In Inheritance II (all works 2019), the narrative seemed more direct than in many of the other works that were on view in this exhibition: The central figures appear to be a mother and daughter. The girl, in the foreground, is languorously posed at what resembles the foot of a bed in a position suggestive of a benign presexualized odalisque. The mother reaches downward to tenderly touch her child. Though the interaction is depicted clearly, its implications remain open-ended. Is the daughter or the mother ill, or are both merely resting? Complicating this interpretation are the awkward, disembodied doll- like feet (a specter’s?) that walk on the back of the matriarch. One can imagine the mother reaching out her hand in an impossibly hopeful act meant to share a generational accumulation of knowledge, history, or familial love. Whatever Ruznic’s intent, this painting is a poignant evocation of affection, rare in contemporary art.

In the large, complicated painting The Wailers, several figures stand upright in a jumbled procession. Suffering seems to be the theme. Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, 1937, comes to mind, conjured by a tilted head moaning a painful lament. Because Ruznic was born in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1983 and emigrated to the US in 1995, it is not difficult to frame these paintings as rediscoveries and transformations of an elusive and painful past, the artist’s dreamlike means of finding rapport with the people of her birth country—or perhaps these canvases memorialize those women who might otherwise be lost to historical neglect or cultural forgetfulness more broadly.

In Truth Seekers, a trio of spectral women are rendered as visionary scientists or shamanistic medicine workers tapping into nature to unleash some internal power. Light bounces around the world of the canvas— populated by plants and mountains—such that the transparent figures seem to subsume everything around them directly into their bodies. This could be a religious painting for the irreligious: Three wise women show that we are part and parcel of the world. The piece functions as a healing balm in the face of the desolation that Ruznic’s art often embodies— especially in her more dire-looking black-and-white drawings.

In Search of New Hope served as a bookend: Several boneless, stretchy characters are arranged in a circle suggesting a family; a central woman stands, holding a monkey-like baby. Huddled in a mass of muted ochers, the figures look to have been cut from the same cloth. By overlapping and integrating their forms, Ruznic points to our inability to exist in isolation and to our inexorable debts to each other. Armed with that knowledge, the painting’s title implies, we might gain “new hope” with which to reinvigorate our lives.

– Matthew Bourbon