October 1, 2020

Mathew Cerletty’s precisely rendered pop paintings bring authenticity to idealized household objects.

Mathew Cerletty, Bashful Lilac, 2020, oil on linen, 51¼ × 51¼ inches; 130.2 × 130.2 cm

Mathew Cerletty is balancing a four-month-old baby with a painting practice that requires the hyperrealism he is known for. The artist doesn’t seem to mind the juggling act though, or the slower pace brought on by the pandemic. “In a weird way, it’s been sort of nice,” he says. Born west of Milwaukee in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, in the Menomonee Valley (former Dallas Maverick point guard Devin Harris is also from the area), Cerletty says, “Becoming an artist was lucky because it wasn’t a path I could see clearly where I grew up. But my parents were open and supported my interest, and possibilities expanded little by little.”

Ultimately landing in the Big Apple, he says, “I was always drawn to cities as a kid, and I kind of worked my way up to New York City. I went to college in Boston and then lived in San Francisco for a year. I moved to New York in 2003, after I started showing my work there with a youthful gallery called Rivington Arms.” The Boston University College of Fine Arts, where he studied and where “representational was encouraged, abstract was not,” urged him toward a career as a portrait artist. Using friends and family for his hyperreal portraiture, he recalls, “When I was younger, I couldn’t imagine doing a painting that didn’t include a person. So it felt daring the first time I did it.”

Following his move to New York, Cerletty says, his portrait work initially continued, “but my sense of the possibilities of painting expanded so rapidly,” and spurred him to try new things. “In retrospect, I think the people in my paintings started to feel unnecessary, like a third wheel. The people in the work had become me and the viewer, and we didn’t need to be depicted.” For several years now the artist has replaced friends and family with objects as his sitters.

Mathew Cerletty, Snow Shovel, 2020, oil on linen, 84 × 36 inches; 213.4 × 91.4 cm

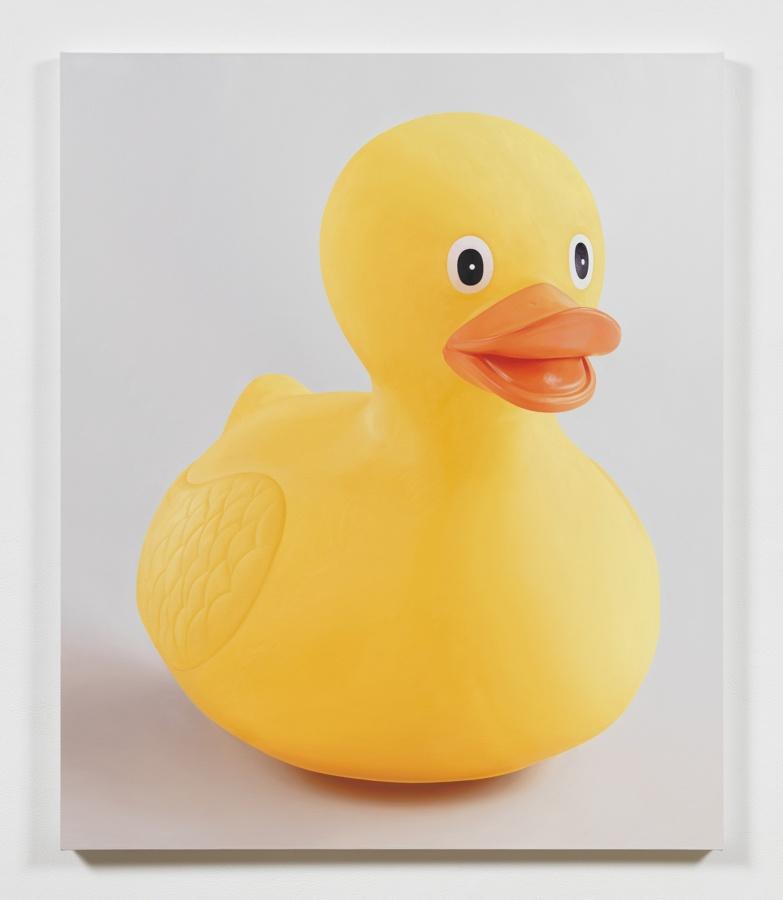

Mathew Cerletty, You’re the One, 2019, oil on linen, 48 × 40 inches; 121.9 × 101.6 cm

Mathew Cerletty, Dry, 2020, Oil on linen, 69 1⁄4 × 52 inches; 175.9 × 132 cm

Today’s call finds the painter preparing for the solo show Full Length Mirror at The Power Station, a nonprofit art initiative envisaged by Alden Pinnell. “I’ve been doing these commercial photography/stock image paintings of idealized household objects. They’re pop portraits isolated on single-color backgrounds” he describes as “context-free spaces, depersonalized to leave room for the viewer.” Attracted to the “imposing personality and texture” of The Power Station and its utilitarian origins as the circa 1920 Dallas Power & Light Building, he loved the idea of bringing his paintings to the space. “This group was conceived with the idea in mind that the exhibition space itself would complete the work and give the lonely objects a home.”

While viewers may be tempted to ascribe Duchampian readymades “visual indifference” to Cerletty’s work, they would be mistaken, for Cerletty approaches the banality with tenderness and sincerity. “I think being a Midwesterner adds a certain level of earnestness to my approach,” he muses. And unlike Belgian surrealist René Magritte, who framed ordinary objects in impossible milieus, such as The Listener in the Menil Collection; or mislabeled, like The Treachery of images (This is not a pipe) a combination of image and text at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Cerletty brings self-awareness to the overlooked objects, often positioning them as a person might pose for a yearbook photo; Mut(u)ate Unity is a nice example.

There is a ready-made fondness in much of the work, like You’re The One and Bashful Lilac—the latter so hyperreal it appears to be a photograph from the stuffed toy’s maker, Jellycat. Cerletty painted the piece about a year before his son was born. “Maybe it’s about anticipation of impending parenthood,” he suggests. He plans to keep Bashful Lilac, so in essence the painting is “a gift to the baby,” though it will be on view at The Power Station for about six months. Pink Pelvis, a painting he hadn’t yet completed as of press time, developed when his baby boy was born in May, at the height of COVID in New York City. Cerletty and his girlfriend “took baby classes in the lead-up, with lots of charts. Those experiences helped me recognize the potential of this image.”

His image selection is unmistakably chosen through the painter’s eye. “It’s about finding subjects that are well suited to showcase painting itself and feel open to multifaceted interpretation. Because paintings are supposed to be ‘special,’ it feels right for the subjects to undercut those expectations, at least at first. I believe in painting, and I’m proud to be part of the tradition.”

Many objects, like Manila Envelopes, though executed beautifully, may seem mundane at first glance. The artist hopes, however, the viewer adds meaning. “They can contain material that runs the full range of significance, from divorce papers, birth certificates, a deed to a new house, all the way down to the most tedious paperwork.” The envelopes “possess an unexpected visual punch with their unusual color, that pale ochre that’s instantly recognizable but also a bit odd and specific. And the small clasp, shiny metal being a classic vehicle for painting to show off.” Cerletty clearly enjoys his mastery. “I get a kick out of defying my own expectations. They are labor intensive and technical.”

Viewing brings a sense of melancholy to much of the work, “Life is fundamentally heartbreaking. There’s a ‘Rosebud’ quality to these objects. And hopefully there’s humor too, but I wouldn’t use the phrase tongue-in-cheek. I know painting a jet ski is funny, but hopefully it’s more than that too. Making these paintings takes a long time, so I really have to care.”

In a nod to the modern crisis, Context, included in the show, sprung out of a mindful, socially distant Zoom call with his parents, whose inexperience resulted in their faces completely absent from the frame in favor of the crown molding around a ceiling corner, offering evidence of things seen. A drawing of a vent is also included in the show.

The artist looks forward to his solo show opening November 14. “It’s really fun to think about the original purpose of the building, now generating art power,” he says, adding, “Alden deserves credit for that. And hopefully that history will now give a few more household objects a little extra life.”